Chin: It's the first time I am looking at myself and my work ... a sort of visual autobiography (Photo: Kenny Yap/The Edge)

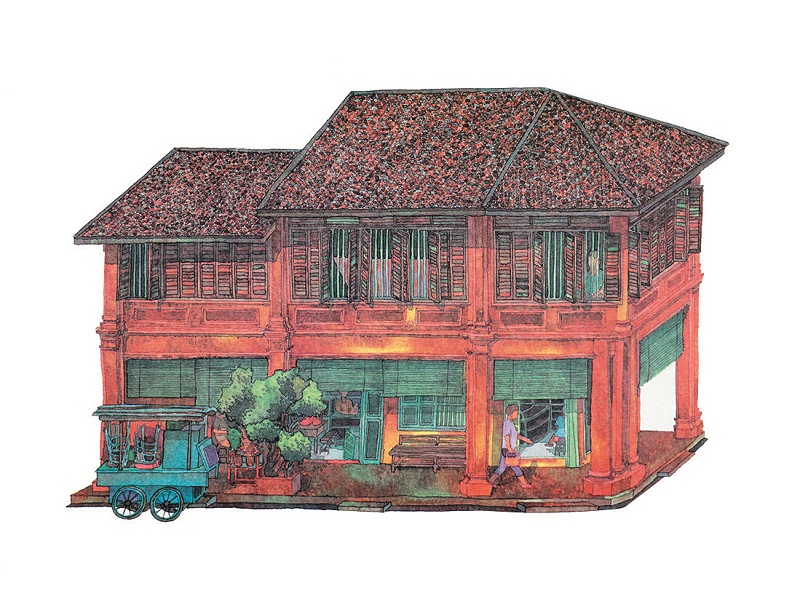

Victor Chin’s colourful paintings of colonial architectural façades show his consuming passion and love affair with such structures that have endured for over 40 years. The 64 watercolours of pre-independence buildings that he painted from 1980 to 1995 are not just a visual feast but also the catalyst that has spurred the artist to champion the conservation — or, at least, the documentation — of these edifices.

A few of his paintings hang in the main hall of Alliance Française de Kuala Lumpur, a not-for-profit association located in a repurposed colonial mansion where his latest exhibition, Fixing Memories, is being held. “I’ve chosen 16 for this show, a kind of retrospective,” he shares.

Also on display is a walking tour map of KL’s Chinatown that he did in the mid-1990s, copies of which are available for purchase. But we are not here just to look at old paintings.

Collectively, the works represent fragments of what is no longer in existence. The map records the place where Abraham, a tobacco seller, used to have his sundry stall, as well as the cake seller, sieve seller and “all the [sellers of] traditional crafts along this street [which are] gone”, says Chin.

no_124_lebuh_cintra_penang.jpg

Similarly, the majority of the straits settlement buildings that he painted either have been demolished or are not quite what they once were. Even the artist has, to some extent, moved on, having laid down his brushes for some two decades. He spent the time writing and getting involved in activism, working with communities like the Kampung Hakka folks in Mantin, Negeri Sembilan, to fight for their land rights.

But the thing about first loves is that they linger, at least according to the self-confessed romantic. “In the last few years, my first love, painting, has been whispering to me, ‘Eh, why have you been unfaithful to me?’” laughs Chin.

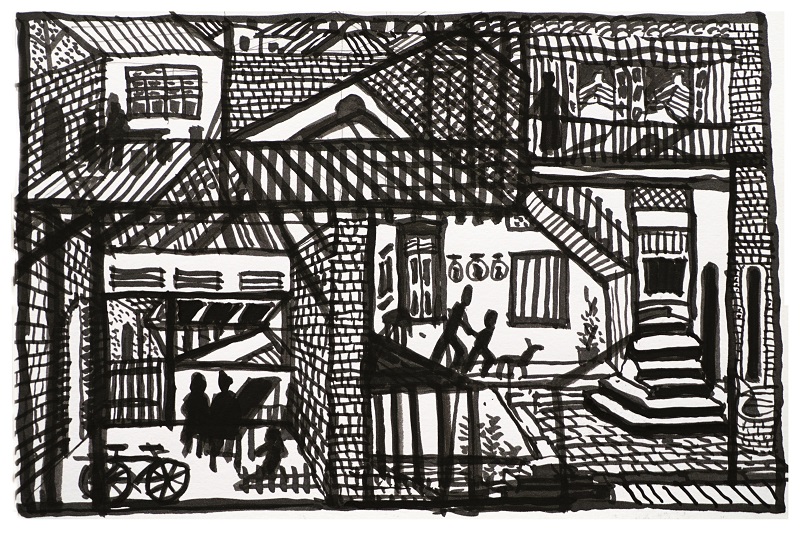

In front of four small pictures, which stand out among the rest for their monochromatic tone and distinctive visuals, he says, “I started doing these small, intimate drawings a few years ago. They are like collages, a form of magical realism, I’d like to think, where rather than a straightforward perspective, they present a different way of looking [at things].”

In one, Kathmandu (2019), Chin outlined fragments of the city that remained in his memory, putting traditional stupas, temples, palace grounds and street scenes into a compressed square. “It took me two days. I’d sit at coffee shops and take in the atmosphere, walk around a bit, then draw.”

ink_drawing_of_a_shophouse_in_melaka_2014.jpg

Another, depicting a traditional Japanese house he stayed in during a visit, weaves together the rooms and corners that caught his eye, resulting in an abstract patchwork defined by lines and strokes. He describes it as a practice in perceiving space from an Eastern and Oriental perspective, one that allows more room for surrealism and idealism.

“I see it as a continuation of my watercolours — just more creative, fun and more of capturing an atmosphere, though the simple element of documentation is still present,” says Chin.

Apart from working on these drawings, he has been steadily honing his skills in another artistic pursuit in the last few years. After being offered an artist’s residency at the National University of Singapore’s Tun Tan Cheng Lock Centre for Asian Architecture and Urban Heritage in 2017 and 2018, he received a grant to create a film documenting the very architectural works he first painted a few decades ago.

The first part of the film series, titled Moved Out, focuses on Singapore and Melaka. The 17-minute documentary — now on YouTube — shows wide and close-up shots of façades and buildings that many of us would walk past without much thought, their pre-colonial and colonial identities faded into the back of our consciousness amid surrounding skyscrapers and modern structures.

Chin’s voice briefly brings our focus back to the origins of these vernacular buildings, most of them built by unknown craftsmen and pioneers before the nation even came to be. In Singapore, we get glimpses of Boat Quay at the mouth of the Singapore River, a few short rows of shoplots now mostly known for their dining and drinking establishments.

Its archival photos of past life and clips of community activities are interspersed with Chin’s own artworks, with the artist explaining the architectural details of the façades, namely the contrast between what they looked like when he painted them and how they appear today. He also peppers his narration with anecdotes about those who had lived or plied their trade in those buildings. For Melaka, he similarly details key buildings along Jalan Hang Jebat, better known as Jonker Street.

no_97_jalan_hang_jebat_melaka_1995.jpg

“I’ve done films on my own for five years now, starting from when I got a grant from the Freedom Film Festival, specifically to cover the Rakan Mantin movement. They gave me some training and mentorship through the festival network, and it started my interest in filmmaking,” says the 70-year-old, who has also made a film about the demolition of the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce Building in Hill Street, and another about the former female leaders of the Malayan Labour Party in Penang during the 1960s.

Chin is currently working on the second part of Moved Out, which highlights the architecture in Penang and Kuala Lumpur. He says this project is especially close to his heart. “It’s the first time I am looking at myself and my work, as a sort of visual autobiography.”

While he does feel a certain sense of urgency about the architecture, the artist says it is never really about the buildings. “It’s not about keeping the shell. Things do change and have to change, but often, the preservation done or even the branding of heritage given to these sites … the price of keeping these shophouses has been the disappearance of the soul of the city.”

It is a consumeristic approach that has drastically and swiftly pushed out what should have been a more natural evolution for these urban communities and their way of life, remarks Chin. “It’s not saying what is being done is wrong, but it asks the question, ‘How can we do better?’”

His favourite quote from Mahatma Gandhi is, “A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members”. In other words, “you don’t measure a city by how well it looks after the rich, but by how well it looks after the poor”, says Chin.

“I think it’s a deep romance, the love of seeing and feeling the atmosphere of a place … of the conditions, the smells that make you feel it’s unique. I’m happy to be a romantic in the traditional sense, not in a sweet, silly way, but to be a radical where you’re moved by the spirit of change for the common good. You measure a city by how well it looks after its streets … that’s what it’s about,” he sums up.

'Fixing Memories' , Alliance Française de Kuala Lumpur, 15 Lorong Gurney, KL. 03 2694 7880. Until Dec 18. Tues-Sat, 9am-6pm. Free admission.

This article first appeared on Dec 9, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.