Emerging artist Yeoh Choo Kuan holds his fourth solo exhibition Streaming Mountains (Photo: Mohd Izwan Mohd Nazam/The Edge)

This month, the upstairs exhibition space at Richard Koh Fine Art is awash in black and white as emerging artist Yeoh Choo Kuan holds his fourth solo exhibition, titled Streaming Mountain. He does not include his first post-residency showcase in 2012.

While visually striking at first glance, it can be tempting for one’s eyes to just glance over the monochromatic works. After all, simplicity is at the heart of each visual in Yeoh’s abtract style .

But I would urge you to take a second look and take time to quietly contemplate the works. I found an arresting quality to them — and this was before I probed the mind of the soft-spoken artist and gained more insight.

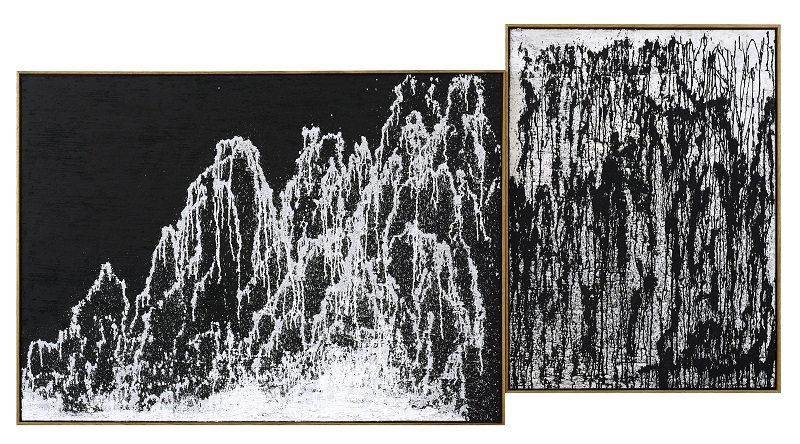

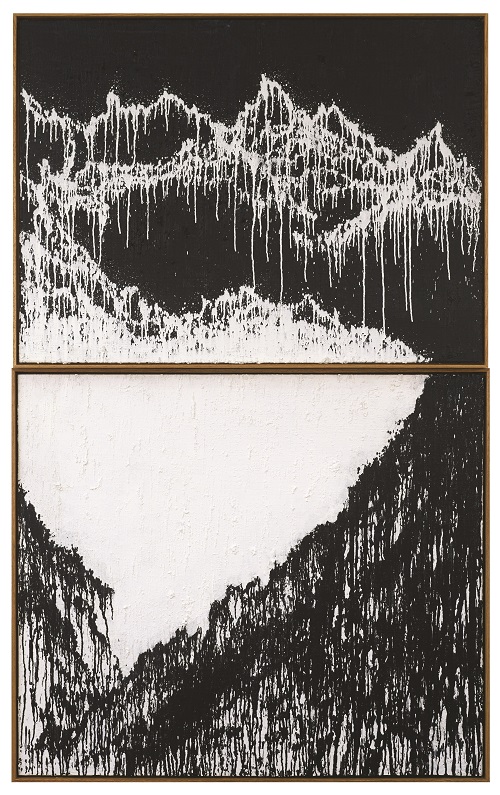

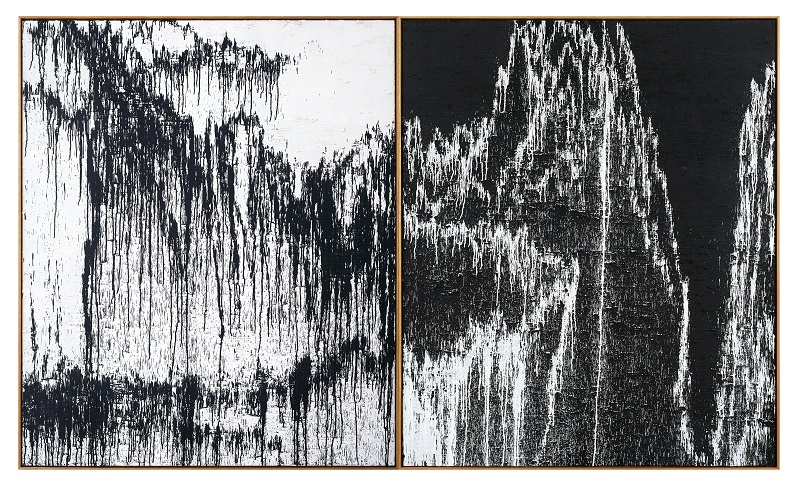

Comprising sets of paintings, mostly in pairs, with the exception of one monumental octaptych (eight panels), the series features dripped paint over textured canvases, which are created using a scratching technique — a signature method of the 30-year-old artist, christened “fleshing abstraction”. The peeled and coagulated texture in turn brings out an expressiveness in the paint drippings — a new exploration for Yeoh — which run and splash in many different directions.

The splashes are not indiscriminate but, rather, deliberate to form the mountain ranges in the vein of Chinese ink landscape paintings. A juxtaposition of Western technique and Oriental aesthetic, it is perhaps Yeoh’s most honest effort yet — one that might prove seminal for his artistic career.

“As Chinese Malaysians, most of us didn’t grow up with Chinese ink paintings … those images are not really relevant to us. But they were somehow at the back of my mind ... and subtly, the Eastern aesthetic influence has always been there. When I reflected, they brought me back to the days I spent at the temple growing up, where these works are seen. In that sense, the development of my works is also a journey of discovering my own identity,” says Yeoh.

Born and bred in Kota Baru, Kelantan, he remembers frequenting the Taoist temple in his neighbourhood. It was there that he first encountered the visuals that would become the crux of his art and the common thread in all his works so far.

In his artist statement, he reveals a fond memory of discovering an illustrated book on Diyu, the Buddhist depiction of hell. It developed into a life-long fascination with violence. “It was weird,” Yeoh reflects with a smile, “I felt guilty that I was so excited by these images within such a spiritual environment. They were designed to scare, yet I was so inspired by them.”

He also professes to be a fan of horror movies, more specifically of the Giallo sub-genre with psychological and mystery elements. Recounting an eye-opening experience watching his first horror film — The Cell, starring Jennifer Lopez — Yeoh says the highly-stylised film sparked his imagination and creativity in a life-changing way.

“Visually, violence is so strong that you just can’t hide from it. I didn’t really think much about it growing up, but when I started my art career, I dug into myself a little more to understand where these interests came from, and I realised my interest leaned towards how violence affects us as a community, how these visuals and acts affect us, especially in this era where you can find anything online,” Yeoh shares.

A deeply personal experience in his teens, when he witnessed a difficult and traumatic episode at home, also played a role in his fixation. He admits that it taught him to shut down his emotions. It had a defining, if indirect, influence on his creative process.

“For me, the input of violence in my work is from the process of making the art, rather than the final outcome of the visual. By allowing myself to execute it — to scratch the painting itself — is like infusing the idea onto the canvas,” he explains.

While we may not fully understand the psychological obsession with violence, the possibility that anyone can have a tipping point, a violent outburst in a moment of madness as release is not implausible or alienating. Indeed, standing up close to one of Yeoh’s works, where the “scars” and “wounds” of the art become much more evocative, there is an almost visceral effect and resonance.

“My art is not really here to judge whether it is right or wrong, but to confront the nature of human beings — to invite you to face it. It’s up to you how you want to deal with it,” Yeoh says.

In inviting the viewer to find their own revelation, the artist eschews impressing for simplicity, stating, “From the beginning, I have always tried to find a pure expression in my paintings. I think when the visual language becomes simpler, it speaks even more. It opens up more possibilities.”

The dripping element introduced in this series adds a new dynamic to the layers behind Yeoh’s art, alluding to ideas of impermanence, fluidity, violence and even sexuality, depending on who is looking at it. He lays bare the progress and process of it through behind-the-scenes video footage that accompanies the show as well as in the artworks themselves.

Two sets of works with a yellow-tinged white paint expose the early stages of his experimentation with the technique, which dominates the visual with a more chaotic expression. Even the scratching here is done horizontally, as if repeatedly cancelling out the imagery.

“I completely ignored the figuration and illustrative part of the creative process with these ones,” says Yeoh, “I was also wrestling with the conflict of whether to show the Chinese landscape painting inspiration. I wanted to really show the paintings as abstract and not reveal as much of the mountains, so you can see so much struggle and uncertainty in them.”

The mountains emerge increasingly in each work of the series, with the landscape imagery being most revealing in the octaptych. The paint drippings on it also show a well-honed finesse, commitment and clarity that seem worlds away from the more primal and instinctive first works.

Yeoh says the creative process on these works was the most liberating he has experienced, as he began to resolve the conflict that always warred within himself and fully embrace his past, his roots and his aspirations influenced by Western techniques, or as he describes it, a “Quentin Tarantino-esque energy of outrageousness and grand style”.

This is indirectly fulfilled in Streaming Mountain’s contemporary and edgy flair of monochromatic imagery, a sense of surrealism and melting seismic graph-like aesthetic, which reflect his Western art training and refreshing rebellion against the classical Oriental sensibilities of beauty.

A pair of works featuring plain black canvas offers a sort of end-credit scene to this series, though Yeoh is always working on the sequel, building on the paint dripping element in a new series. And with a large installation work showing at Art Stage Singapore 2019 late this month, he is certainly riding this new groove.

For now, he leaves us a final reflection: “As children, we are taught to make decisions in black or white. Then as we grow up, we slowly learn that not everything is black and white ... it’s not that definite. Slowly, we may find black is white and white is black. What is truth? Which is real? It depends on your perception.”

Streaming Mountains, Richard Koh Fine Art, 229 Jalan Maarof, Bangsar, KL. 03 2095 3300. Until Jan 30. Tues-Sat, 10am-7pm. This article first appeared on Jan 14, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.