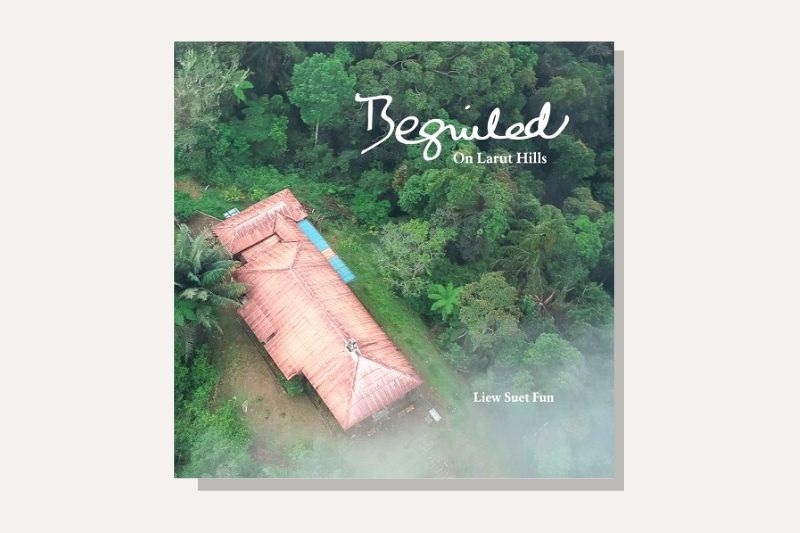

Beguiled: On Larut Hills is a book on the geography, history, immense biodiversity and primeval beauty of what was formerly known as Maxwell Hill

People need language to reconnect with the natural world. Words help us notice things and evoke emotion and empathy. When we are moved by nature under threat, chances are we will do something about it.

Writers cannot just say how wonderful or beautiful a place is and stop at human aspirations, says Liew Suet Fun. With climate change, environmental degradation and the loss of plant and animal species happening around us today, “we need to bring back that connection”.

Language is the most powerful tool people have because “it enables us to link back to spaces and memories we have forgotten in our busy lives. When you see something and are able to describe it, you have a bond with it”.

Liew hopes to forge that bond with Beguiled: On Larut Hills, a book on the geography, history, immense biodiversity and primeval beauty of what was formerly known as Maxwell Hill, early residents of the colonial hill station, and the need to conserve the 6,878ha forest reserve and relook man’s relationship with landscapes.

She takes a page from writers who are reconnecting readers with nature. In 2017, Robert Macfarlane wrote The Lost Words after everyday nature words such as acorn, bluebell, kingfisher and wren were removed from a children’s dictionary because “they were not being used enough to merit inclusion”. His illustrated spell book, a “cultural phenomenon” said The Guardian, has become a celebration of the natural world as well as a protest at its loss.

liew_suet_fun_wrote_beguiled_1.jpg

Larut Hills is 10km from Taiping, where Liew was born, left at age 19 to study English Literature at Universiti Malaya, and returned to live almost 40 years later. Whenever she visited on occasion, the familiar lines of those magical hills, for which she had a curious affinity from childhood, reminded her she was home. For her, and many of the townsfolk, it was “a surety, a perennial marker of our space in this vast universe”.

Liew is in a good position to write about Larut Hills as she is ensconced in The Nest, one of about 10 timber bungalows built by the British in the 19th century. The only way up is to trek or take a Land Rover, which has to weave around 72 hairpin bends and old footpaths.

The Nest is removed from its neighbours, which have views of surrounding towns and shorelines and were expressly for the recreation and social interaction of the colonial government and its officers. It was built within the forests in 1887 for the private use of John Fraser, the Scottish businessman who lent his name to beverage company Fraser & Neave.

Fraser, whose family was living in Singapore, had interests in timber, construction and brokerage and spent time in the bungalow until 1904. Before returning to England, where he died three years later, he offered the property to the American Methodist Mission for use as a retreat. Subsequently, many who served the mission did that, falling asleep to the sounds of insects and waking to the call of monkeys.

In the early 1990s, for want of a caretaker, The Nest was left unattended and the forest began to grow over it, Liew writes. There were funds to refurbish the building and expand occupancy in the mid-1990s, but no takers. In 2016, when the Mission decided to lease it out, she and her husband Peter Matu signed a lease for five-plus-five years. They met in Kuching in 2011 when Liew did a project for the World Wide Fund for Nature, Malaysia.

the_nest.jpg

Handyman Peter, a Kelabit from Bario, Sarawak, where they lived for three years before Larut Hills, fixed up the bungalow and made it home. “As there were very few other options in the hills, we decided to let people share our experience as the church had always run it as a place of retreat.”

Becoming homestay operators by sheer fate threw them into the deep end. Liew had to cook for their guests while Peter took care of the grounds and fixtures. They drive half an hour down to Taiping for supplies but have to walk up a 300m stretch to reach The Nest, lugging groceries and whatnot.

“After three years of living there, I felt equipped in some way to write about the hills and Taiping — it was on my bucket list. So we stopped taking guests from March last year and I wrote intensely for six months,” says Liew, who has 14 non-fiction books to her name. An early work, Gilding the Lily: Everyday Portraits of Malaysian Women, was published by the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development in 2007.

As hosts, they met visitors, many from the city who came to be with nature and fell in love with The Nest, as well as those who only wanted to party and take selfies. Children, particularly, were enthralled and embraced the things around them. While the adults worried about leeches, snakes and flies, they turned to moths, butterflies, beetles, stick insects, rocks and plants.

In 2018, talk about a cable car service to Larut Hills resurfaced, but a state government official said there were no plans for such a project. The proposal, which crops up every few years, gave an urgency to Beguiled. Liew sees the local community connecting to the book because of their experience of the hills, which have retained an old-world charm compared with Cameron Highlands and Fraser’s Hill.

People ask her what the title means. To beguile means to enchant, which has the notion of deception, she explains. Nature and humans have dual natures: Moths deceive to survive; we are the same. The book is about a setting that is not perfect, with thunder and copious rain, but there is a rhythm. Beguiled summons the duality of our existence.

Bario, where the Kelabit are patient, instinctual, tough and have very close contact with the Earth, prepared Liew for Larut Hills. “It altered my perspective; you begin to see what you need or don’t need and what is really important. Having only 2G access was a shock — I couldn’t check what was going on in the world. Then you realise the headlines never really change.”

What has changed for her is learning to do other things and enjoying the stillness of her surroundings, under a blanket of mist. Liew writes about the genesis of the hills, ancient fern trees, hidden waterfalls, moonlight magic and creatures that find their way to her door. She includes photos and accounts by those who lived in the hills, or spent memorable family holidays in bungalows like the Hut, Speedy’s, Treacher’s and Hugh Low.

When the Covid-19 pandemic settles, Liew hopes to introduce half-day guided tours to The Nest, so more people can gather information about the hills and appreciate their unique value.

“They can come and look at the bungalow, which is in fairly good condition and quite typical of a British-style colonial bungalow anywhere. We can have tea, then go for a walk and talk about the natural history of the forests and the heritage aspect.”

The pair plan to be selective and keep the groups small. Sometimes, big parties head uphill to talk, eat and snap photos. “The birds and cicadas are calling and we point that out to them but… There are bigger bungalows run by the Taiping Municipal Council and we direct them there.”

There will be another book, about Bario and the elemental Kelabit community, based on Liew’s experience of living with them. “We have to balance the time,” says this former public relations consultant who gave up her well-paying job to write full-time at 45, “the last window because past that age, it would have been harder for me to make the leap”. She will be 60 in August.

This article first appeared on May 25, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.