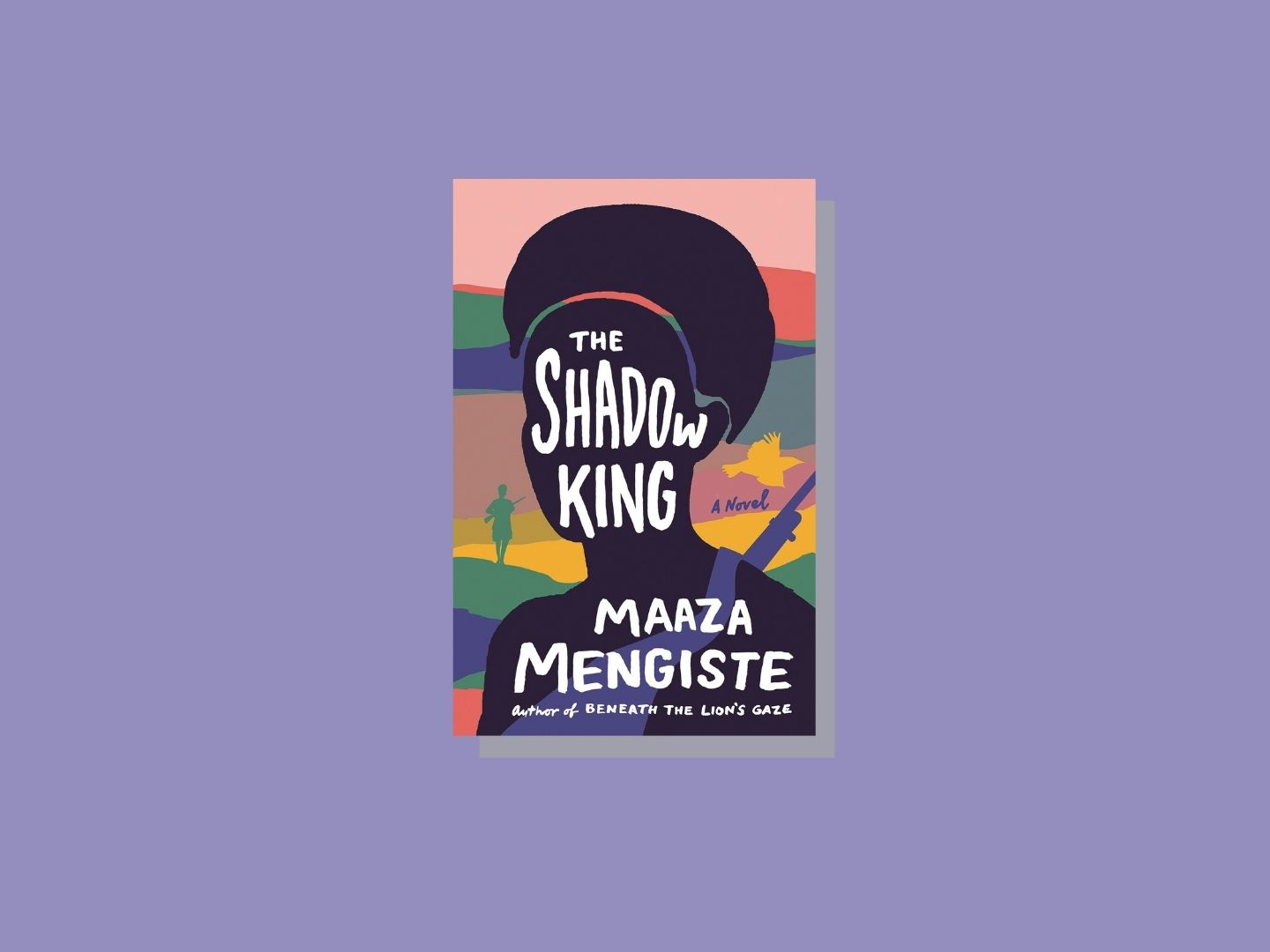

The lyrical novel is set against the real backdrop of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (All photos: The Booker Prizes)

Tales of war are often told by men about men while women slip through the fingers of history. In The Shadow King, American-Ethiopian author Maaza Mengiste attempts to redress this injustice in her own family, whose recollections hail the heroism of outnumbered Ethiopian soldiers but brush over how her great-grandmother Getey fought in court for the right to join the war.

“She does not want to remember but she is here and memory is gathering bones.”

And so begins the lyrical novel set against the real backdrop of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. As Mussolini prepares to invade her native Ethiopia in 1935, young orphan Hirut arrives at the home of Kidane and Aster — he, an officer in Emperor Haile Selassie’s army, and she, a jealous wife locked in grief over their baby’s death. Aster immediately takes offence against the pretty maid and their complex relationship — a stew of resentment, guilt, defiance, grudging admiration and compassion — shapes part of the subsequent events.

While her husband readies the villagers for imminent war, with pride and courage their greatest weapons in the face of gross armament shortage, Aster rouses herself from the marshes of sorrow to rally women near and far. Although Kidane insists they behave as women should — organise supplies, care for the wounded, bury the dead — they learn to make gunpowder for empty shell casings and defend themselves and the soil they fight for. And when the emperor turns tail and leaves his falling country to its fate, it is Hirut who erects the titular Shadow King: a lookalike of the emperor to galvanise the floundering spirits of the troops. “To be in the presence of our emperor is to stand before the sun,” proclaims one of the fighters.

1200px-maaza_mengiste_at_bookexpo_05586_cropped_1.jpg

Mengiste experiments with narrative devices, juxtaposing straightforward chapters that propel the story forward with interludes, a Greek chorus and scenes described through photographs. The last is the work of Italian army photographer Ettore Navarra, who is recruited by the sadistic Colonel Carlo Fucelli to document the ongoing war from the perspective of the assumed victors. The individual stories are layered together, seamlessly flitting between those of Hirute, Aster, the emperor, Fucelli and Navarra. This merry-go-round of viewpoints and devices can be disorienting, especially as inverted commas to signify dialogue are absent, but once you sink into its rhythm, the story unfolds steadily enough.

War is a tricky beast to write, to walk the fine line between beauty and grotesqueness — bloodshed and brutality are often romanticised through the lenses of patriotism, or its horrors explicit with voyeuristic relish. In this, Mengiste wields her pen masterfully, striking that right balance of objectivity and sympathy in the telling of assault, punishment, the hanging of a young boy, a madman’s cruel delight in throwing prisoners over a cliff.

Power struggles abound throughout in the exploration of sexual politics, class and race issues (“Imagine her like a beast to tame, a dumb and frightened dog”). Mengiste also cleverly depicts how rebellion and the fight for dignity is not always loud or violent but also exists in quiet insolence, such as the intentional mispronunciation of Mussolini’s name, or cunning, the way a girl calculatedly yawns to deflate her rapist when she realises she is no match for him physically. Key characters are well fleshed out, as vulnerable as they are valiant or vindictive, and are pushed to wrestle their individual demons, evoking the human amid the inhumane.

There is little doubt that the author is incredibly accomplished, going by her technical prowess and cadence-rich prose, but a stricter editor might have made some tweaks. Male voices frequently dominate and I am left wanting more from a few female characters cast in the sidelines, unexplored, despite their important roles in the story. Her sophomore novel is also overindulgent in its use of light as a stage direction and allegory, recurring (almost maddeningly) in every couple of pages to literally illuminate the protagonists and shroud antagonists in shadow.

But the flaws are minor considering the scope Mengiste tackles. This is a tale of many wars fought at once — private, interpersonal, across borders — and the complexity of man. But this is not a story about men. It is very much an homage to heroines long unsung, who time and again have heeded similar calls of duty and fought fearlessly at the frontlines.

See the Booker longlist of 13 books here. The shortlist of six will be announced on Sept 15 and the 2020 winner will receive the £50,000 prize in November. Each shortlisted author gets £2,500.

This article first appeared on Aug 31, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.