Hajeedar's firm, Hajeedar and Associates Sdn Bhd (HAS), recently celebrated its 42nd anniversary in practice with more than 100 buildings completed around Malaysia and abroad (Photo: Kenny Yap/The Edge)

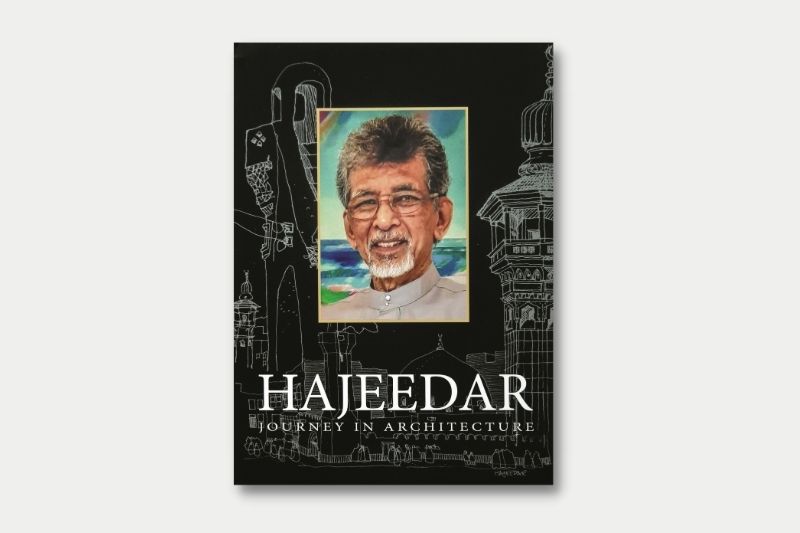

Datuk Hajeedar Abdul Majid recounts an illustrious and colourful career in his autobiography, Hajeedar: Journey In Architecture. The weighty tome is organised into three parts: an autobiography, an account of his practice and a collection of papers and speeches on various subjects delivered over the years.

Hajeedar’s career as an architect is formidable. His firm, Hajeedar and Associates Sdn Bhd (HAS), recently celebrated its 42nd anniversary in practice with more than 100 buildings completed around Malaysia and abroad, including mosques, commercial towers and public buildings — many are award-winning and landmarks now.

He was the seventh recipient of the prestigious Pertubuhan Akitek Malaysia (PAM) Gold Medal Award in 2012, in recognition of a life of contributions, both in architectural design and practice. He received the Board of Architects President’s Medal in 2017 for, among others, his contributions to the development of laws and guidelines in practice.

hajeedar_abdul_majid_at_pam.jpg

Hajeedar is from a formative generation of young Malaysian architects who came into their own in the 1970s and 1980s. This was a period of prosperity and intense nation-building — both literally and figuratively. Succeeding the Merdeka-generation of architects who had propagated and adapted the International Style of Architecture, Hajeedar’s generation grappled with new manners of forging a Malaysian identity in the built environment in the shadow of the interracial strife of the 1960s, and at a breathtaking pace.

Hajeedar was born in Kuala Lumpur in 1945 and grew up in Kampung Baru, playing in its rivers with his friends, much to the chagrin of his senior police officer father. He describes a carefree childhood spent among a “kaleidoscope” of friends that he has retained until today. Once a friend always a friend, he believes. He cites the diversity of his friendships as a defining part of being Malaysian and he laments the level of polarisation observed in society today.

He spent his formative early years in the Pasar Road English School, followed by Victoria Institution between 1959 and 1963 during its “golden age”, helmed by Dr GED Lewis. Drawing and painting were early passions cultivated and guided in school by his art teacher Patrick Ng, who got him involved as a fellow member of the Wednesday Art Group, which included Syed Ahmad Jamal, who would become a national laureate. Hajeedar’s works were acquired and exhibited at the new National Art Gallery when he was just 15 years old, leading to further fee-earning commissions.

hajeedar_abdul_majid_-_hajeedar_journey_in_architecture.jpg

Notwithstanding his tremendous talent at such a young age, Hajeedar aspired to be an architect. He responded to an advertisement for a Mara scholarship to study naval architecture in the UK and scratched out the word “naval” from the piece of paper. This infuriated his interviewers but he persisted and was eventually awarded a conditional scholarship. He excelled in Plymouth Polytechnic in 1966, securing his continued academic funding and completed the second part of his architectural education at Portsmouth Polytechnic, graduating in 1972 before working towards his practical experience in Brighton.

Upon his return as a UK-licensed architect in 1973, his experiences with the Urban Development Authority of Malaysia, though productive, exposed him to the potential pitfalls in the implementation of the National Economic Policy. He delivered a prescient seminar paper in 1978, “Kesan-kesan Penyelewengan Dalam Perlaksanaan Dasar Ekonomi Baru”, warning about the subject but it was to little avail. He did manage to express his views informally to Tun Hussein Onn many years later, true to his candid nature.

In 1983, Hajeedar was appointed director of Pernas Construction Corporation; this was followed by a tenure as chairman from 1987 to 1995. Perbadanan Nasional Bhd (Pernas) is a government-linked company tasked with carrying out the resolutions passed at the Second Bumiputera Economic Congress.

An important paper of his, “Towards a Conservation Movement in Malaysia”, which did eventually gain traction, was published in Majalah Arkitek in 1976. In it, he expressed his concerns for the conservation of heritage buildings in KL. He called for a public movement led by architects and planners, besides the enactment of laws for the listing of heritage buildings. A follow-up paper in 1977 proposed a far-sighted map for the creation of a Kuala Lumpur Conservation Area around Merdeka Square, preserving the stately British Raj-era buildings, including the majestic Bangunan Sultan Abdul Samad.

378335_406235889429861_1303566239_n.jpg

The National Heritage Act of Malaysia was eventually gazetted in 2005 with an inaugural 16 entries classified as tangible architectural heritage in 2007. This was after years of tireless advocating by groups such as PAM and Badan Warisan Malaysia. Hajeedar was appointed chairman of the Experts Committee for the Registration of Architectural Heritage of the National Heritage Department in 2010 and 2012. There are 183 listed buildings to date.

Hajeedar did not wait as long to put his conservation map in motion. Soon after establishing his own practice in 1978, he was approached by the then Lord President of the Industrial Court, Tan Sri Harun Hashim. “Put your money where your mouth is!”, he was told and was presented with the opportunity to convert the Neo-Renaissance Chow Kit & Co Department Store on his conservation map into the Industrial Courts of Malaysia. HAS supervised the careful completion of the adaptive reuse project in 1982, ensuring the building’s continued life. The 5ft verandah walkways on the street level were adapted into the waiting area fronting the lower-level courtrooms, integrating the courts with the streetscape, while the interior courtyard was preserved.

This was followed by a series of adaptive reuse project appointments for three other British-Raj era buildings on his conservation map — JKR 26 Railway Headquarters and JKR Selangor into the Handicraft Museum; the Government Printers Building into the KL Museum; and the Chartered Bank Building into the Jabatan Agama Islam Wilayah Persekutuan Building. All were completed in 1986. In 1989, his practice oversaw the conversion of the palatial Carcosa Seri Negara and the King’s House into a boutique hotel.

20180913_pla_carcosa_seri_negara_5_lyy_tep_1.jpg

In 1978, the local Bangsar resident and architect set about the task of establishing a mosque for the growing congregation of the area. He had settled into the suburb a few years earlier with his wife Sabidatul Majni, whom he had married as a student. The resourceful architect, through interactions with DBKL and a school association in the office of the landowner, Eng Lian Group, managed to secure a prominent site in Bangsar Baru. Utilising a novel town planning instrument, the developer was compensated with development rights from the donated site to one of their other sites in the area.

With some sizeable funds raised by the residents, the government took over the project and HAS was awarded its first large mosque project, which was completed in 1983. It adapted the modern mosque arrangement of the raised open prayer hall as that in Masjid Negara to the suburban tight triangular site but incorporated a voluminous three-storey prayer hall, resulting in a tall mosque with a prominent street-facing façade line.

The mosque’s design incorporated the raw concrete expression employed for institutional buildings of the day. Abstracted Mughal references were made in such motifs as the cutout pointed arched Iwan vaults on the façade and the entrance portico as well as the zigzag pattern at the top of the minaret shaft. The golden dome is inspired by historic colonial-era Mughal mosques, such as the Ubudiah Mosque in Perak, while the folded spire minaret echoes the one at Masjid Negara.

Other mosque projects followed, including the Grand Friday Mosque in the Republic of Maldives, completed in 1984.

grand_friday_mosque_in_the_republic_of_maldives.jpg

Kuala Lumpur’s skyline in the 1970s was relatively absent of towers; it was still lined by two-storey shophouses with its natural topography discernible. This would change rapidly and Hajeedar’s generation of architects were tasked with equipping themselves with the means to design and supervise the required construction of tall towers and in large numbers.

With the appointment of HAS in 1983 for the 29-storey Bank Pembangunan headquarters tower in Jalan Sultan Ismail, Hajeedar procured the use of computer-aided design and documentation (CADD) — the first in the country — and launched the practice into the age of computers. The north-facing tower was designed in three stepping-down volumes to street level, akin to the early New York skyscrapers, minimising the shadow cast upon Jalan Sultan Ismail. Individuated tall volumes break up the east and west façades, minimising glare into the building through narrower glass façades.

Further commercial commissions followed, with the 22-storey Menara Telekom (later Menara Celcom) in Jalan Tun Razak as well as the 27-storey MNI Twin Towers in Jalan Pinang in 1995, and the 22-storey tri-tower Dataran Maybank completed in 1999. These projects utilised curved floor plates to articulate the form of the façade and incorporated sizeable open space at the base, particularly in the latter multiple tower projects. These were some of the city’s pioneering modern landmarks, setting the scene for the Petronas Twin Towers and the ensuing era of the extruded glass boxes.

As many facets as there are to Hajeedar’s career, his autobiography includes varying accounts of the man by colleagues, friends and family. He laid a foundation of technical and regulatory knowledge for the complexities in design and procurement of the building industry and set an incredibly high standard of principled practice for architects.

Hajeedar’s story is firmly rooted in KL, a city that works at a frenetic pace, perpetually reinventing itself for tomorrow. Hajeedar has worked unfalteringly to preserve its connection to its past by providing continuity in building anew along with the preservation of heritage, which we might not know about today if not for him.

This article first appeared on Mar 15, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.