Galeri Petronas takes up a 2,000 sq m circular space touted as a world-class venue designed to promote, develop and preserve modern and contemporary art (Photo: Galeri Petronas)

The news about Galeri Petronas ceasing operations effective this month after 28 years caused blips in art circles the past few weeks. Shock, sadness, dismay, nonchalance and hope were among the reactions voiced by artists and those in the industry.

Galeri Petronas, owned by the national oil and gas company, was established in 1992 at Dayabumi Complex, Kuala Lumpur. Six years later, it relocated to Suria KLCC, below the Petronas Twin Towers, taking up a 2,000 sq m circular space touted as a world-class venue designed to promote, develop and preserve modern and contemporary art.

Shaliza Juanna Alfred was among those shocked by the May 3 announcement on the gallery’s closure “following a realignment of its operating model to adapt to the changes brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic”.

One of those selected for Young Malaysian Artists II in 2014, she put up her first installation piece. “It was a dream come true. After the exhibition, many doors opened for me.” She did her practical training at Galeri Petronas — “an overwhelming experience and I met many friendly and helpful employers” — while studying fine art at Universiti Teknologi Mara, and then taught art at UiTM before returning to Pontian, Johor, to be a full-time artist.

galeri.jpeg

Kedah-born artist Eng Tay, now based in New York, held a solo exhibition at Galeri Petronas and was part of a group show there too.

"It was such a fantastic space for artists to exhibit their work. How unfortunate that a place with such a prime location has to close. It made it so easy and convenient for people to visit. I actually visited the gallery every time I came back home. It has shown many great exhibitions over the years."

Melbourne-based Anurendra Jegadeva, an established name in Malaysian contemporary art, served four years (2007 to 2010) as senior curator at the gallery. “It was an interesting experience,” he says via email.

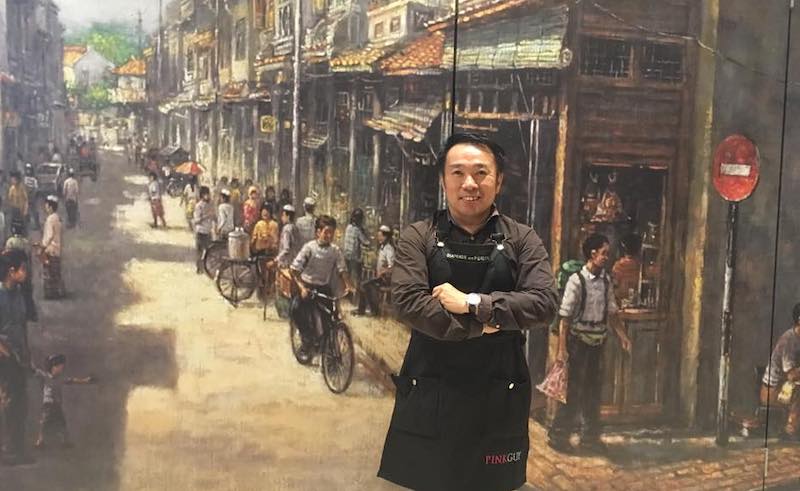

The gallery’s statement that artworks from the Petronas Art Collection will remain available for loan to relevant programmes and initiatives gives WinSon Loh hope. Loh’s PINKGUY gallery has been doing conservation framing on the collection for more than a decade.

“I provide the service whenever the gallery acquires new works. The last few years, the oil price was lower and the economy was affected, so I have been getting less and less work.

“I am sad the gallery has closed. There is talk — I’ve heard only, never seen the details — about it having its own multi-level building near KLCC, with room for its own collection, artists to exhibit and storage.

“If that plan remains, it is good because it will mean a bigger space to show art in future. The gallery has been around for so many years, by right they should have their own building and move there.”

loh_new.jpeg

Lim Wei-Ling, founder/director of Wei-Ling Gallery, remembers the “heyday” of Galeri Petronas under director Tengku Nasariah Tengku Syed Ibrahim, when it hosted serious and iconic exhibitions by local and international artists, invited them to write too, and published books. “It was a dynamic time,” she says.

“Government-backed bodies play an important part in promoting art and providing a curated platform to educate people. There are not enough local institutions to support contemporary art. It’s a shame that Galeri Petronas has closed at a time when art is developing so nicely through interest in it.

“Many young Malaysians are interested in art but there are no places to go. They visit our galleries and we provide free talks and tours in a private capacity because we want them to see and feel what artists want to show.”

Public institutions are gatekeepers for the art world. Lim says Galeri Petronas has a strong, seminal collection and it is good to know they might show it because in many countries, people go to public museums to view permanent collections.

Syed Thajudeen Shaik Abu Talib, known for his figurative paintings, says when the economy of a country grows, arts and cultural activities also will grow. At the time of its founding, Galeri Petronas was run by professional corporate leaders who were also patrons of the national cultural heritage and knew the importance of developing that. “The gallery supported local artists by collecting their major works.”

Over the last 28 years, there have been major changes in the Petronas management. “Old leaders have left or retired, and the thinking culture has also changed. The new management, lacking knowledge in the arts and culture of the country, may have thought Petronas Gallery was a white elephant and an unnecessary expenditure for the company, and decided to close it for good without acknowledging the damage to the future growth of arts and culture.

“It is only a technical mistake. Things can be rectified by changing the mindset,” he says.

galeri_1.jpeg

Collector Pakhruddin Sulaiman goes straight to the point: “Don’t blame it on Covid. It doesn’t make sense that [one of the biggest oil companies] in the world cannot allocate a small amount as part of its corporate social responsibility (CSR) programme to support art.”

Pakha, as he is known, says rumours about the gallery closing had been rife for years. The closure was almost certain until an appeal was made by senior management with reference to the bottom line: The value of its artworks, which had appreciated over the years, saved the fate of the gallery.

“Those at the helm are using the oil price as an excuse now. They are simply philistines. They don’t care about art and don’t know about it. You know, tak kenal maka tak cinta.

“Banks were major supporters of early art development in the country — they were quite enlightened. This kind of endeavour has no strong blueprint as a CSR. If there was, those who came later wouldn’t talk about money and see that the value of art cannot be determined by it.”

As it happened, following the two economic crises, government programmes to collect and promote art dried up and banks exited the scene. “Luckily, private collectors came in to fill the huge hole.”

Pakha laments that Malaysia has failed to develop its art vision — the country has moved backwards while others, like Singapore, have made progress. “The National Art Gallery (NAG) was foremost in Southeast Asia, but Singapore has superseded it. We are quite insignificant now, so small. It’s a pity, this philistine culture.”

On the talk about a new Petronas gallery, he says: “They announced it and were busy head-hunting. Recruitments were made, I heard. A few people were appointed but could not start until the new so-called world-class art space was ready.”

Now, they will reconfigure that space into something else, he thinks, something more commercially viable.

“It’s simple logic — if you don’t have a gallery, what is that space going to be once the building is ready in two, three years? If Petronas is going to have a new museum, why close the current one? You have to prepare. If you have hardware, you need software too.”

Former NAG director-general Wairah Marzuki expresses sadness that “such a stable company is not able to handle its arts centre, this commitment to the country”.

In the 1970s, there was only UiTM. Many art institutions have opened since and the population of artists is growing. Works by Malaysians are recognised and collected by museums and collectors around the world, she says.

“Those in the industry feel very sad that Petronas has decided to close its gallery. The cultural industry is not just about visual art; it’s about music, film, digital art, moving images, and the money is there.

“I don’t know if Covid is a valid reason. Some artists have continued to maintain their activities. Henry Butcher is going strong and Malaysian artworks are fetching high prices at auctions.

“Singapore started late but jumped into it. Art is big in other places too — Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand. Sales through art are part of a country’s growth. People are beginning to know about art, the industry and art investment.”

Wairah, who also has heard about Petronas having a new museum, says artists are looking for prime venues to hold exhibitions. “I don’t know what’s going on but I’ll be excited if that happens. I pray the gallery reopens because the country and the art industry need more involvement.”

A gallery owner who chooses not to be named is nonchalant. “I’m not involved with Galeri Petronas and its closure is not relevant. I feel the set-up has not done much for Malaysian artists — it has no connection with what’s happening on the ground. How many artists have actually shown there or benefited from it? It’s very selective.

“People can talk about the gallery doing a lot in its heyday. But heyday has residual [impact]. There is none — it didn’t make any difference in Malaysian art.”

This insider thinks the closure is an interim measure. “Aren’t they working on a Petronas museum at a site close to KLCC? And it has nothing to do with Covid: If the current space is not active, why bother to keep it? If Petronas is not doing well, find ways to cut costs. The [closure] was probably made from a business point of view.”

He thinks the decision reflects what happens to many public institutions — they are good at the start but fizzle out because those in charge do not know what to do.

“The gallery is a white elephant that just fades away. We all have hope, but somehow, all that gets dashed. It’s a pity because there is one less non-profit art space now.”

This article first appeared on May 17, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.