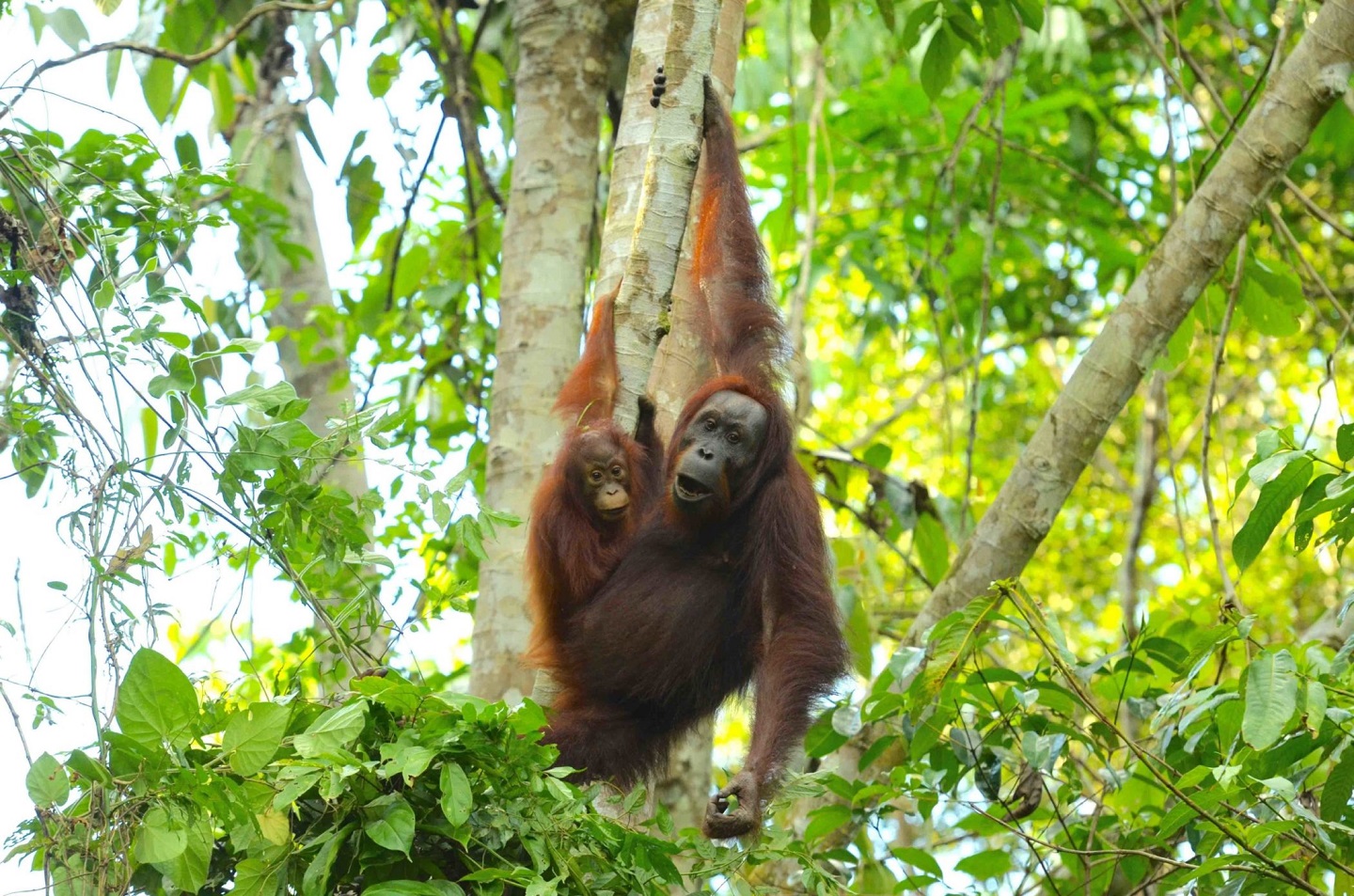

Orangutans are but some of the wildlife that has benefited from Hutan’s research and education programmes, which disseminate messages about conservation and sustainability to the surrounding communities (Photo: Hutan)

In 1994, French researchers Dr Isabelle Lackman and Dr Marc Ancrenaz visited Sabah for the first time to study the orangutan population outside untouched primary forests. Realising that many of these primates were living in disturbed and over-logged forests, the couple founded research organisation Hutan to establish an intensive study site in the fragmented forests of Lower Kinabatangan to observe these animals’ adaptation processes to habitat interference.

Hutan’s overarching objectives are to acquire a better understanding of wildlife needs in highly transformed landscapes, ecosystems’ restoration and reforestation, habitat and wildlife protection, better acceptance of a peaceful co-existence between people and animals, improved policies and land-use planning. In 1998, with the full support of the Sabah Wildlife Department, Hutan established the Kinabatangan Orangutan Conservation Programme (KOCP) in the village of Sukau.

In the late 1990s, Lahad Datu native Datu Md Ahbam Abulani was approached by Hutan to join them in Sukau, and at that time, he did so purely for the money. “I didn’t really understand what they were doing, my priority was to ensure that my family was fed,” he begins. “But when I saw so many researchers from all over the world coming to Sabah, I was curious — what did we have here that so many people were coming to learn about? That really inspired me to learn more about my job and become more involved in what Hutan was doing.

"I started out doing research and field work, which has been the core of what I do till now, and I also communicate with other NGOs and government departments.”

datuk_md_ahbam_abulani_1.jpg

The NGO’s founders were more than happy to support his passion for learning, and sent him for a number of courses to further his education. Now a fierce advocate for environmental protection in Sabah, Ahbam kickstarted and manages the Hutan Environmental Awareness Programme, which disseminates messages about conservation and sustainable use of our environment based on the findings of Hutan’s efforts in the field.

The HEAP team is tasked with, among others, developing educational modules for the community and their dissemination within oil palm estates and villages, and engendering environmental awareness with schools. The gentle-natured Ahbam has also spoken about the topic at events and conferences all over the world.

Prior to Covid-19-related travel restrictions, the HEAP team was constantly on the move — not only have they successfully visited almost every non-urban school in Sabah, they also communicated regularly with officials in the Ministry of Education and other relevant bodies to further their unique agenda. Although many NGOs have since acknowledged the role of education in the community, Hutan — Ahbam, in particular — was a pioneer.

“We started out by providing training and education to our own staff — the programme didn’t have a name just yet,” he recalls. “It was intended as a capacity-building programme for our own team, which we then expanded to include their children. It then occurred to us that research alone wasn’t enough to make an impact with the community-based conservation approach we had in mind.

"We interviewed people — right from those living by the Kinabatangan River to government officials — to find out what the current level of understanding was in relation to wildlife conservation, and it was quite poor. That was when we decided to create HEAP and provide environmental education for rural schools. Subsequently, we became part of SEEN (Sabah Environmental Education Network) and also worked with the Ministry of Education to continue partnering with schools to provide wildlife-related modules for children.”

hutan-berjaya_elahan2.jpg

The modules were developed based on existing knowledge and understanding of the natural environment in Sabah, and were designed and delivered in a way that would best suit the local community, with support from foreign partners and funders such as Chester Zoo in the UK and Houston Zoo in the US. “We want the community to understand that we have to live together in peace,” says Ahbam.

This understanding comes from his childhood, as he loved spending time in nature, especially Lahad Datu’s lush forests. After finishing secondary school, he worked in the logging industry — a common job back then. He laughs at the irony considering his work today. He had a keen eye for detail and eventually took on quality monitoring and surveyance roles in timber factories. He grew to love carpentry as a result. After he married, he also worked as a fisherman.

These jobs endowed him with a wide range of experiences that greatly inform his work in community education today — he understands instinctively the need to provide for one’s family, and is proud to show the surrounding communities that this does not need to come at the cost of destroying the environment.

The change in mindset and perspective is hard to quantify, but Ahbam has a more concrete example — the use of traditional fish traps, or bubu. “The kampung folk used to damage trees to make bubu, and this was an example of the kind of conflict I was talking about — they need to fish for their livelihood, but is there a better way?

"We introduced the idea of plastic bubu, which last longer and do not require trees to be damaged when their bark is harvested for making traditional bubu. That programme, which began in 2007, went past Sukau to other villages that rely on fishing to survive, and it has been very successful.”

hutan-marc_ancrenaz6_copy_1.jpg

G8 is another case study in reducing conflict amidst increased encounters between humans and elephants. Hutan worked with the smallholders’ community in Sukau, who were facing conflict with elephants that caused damage to their oil palm crops. G8 stands for Gabungan 8, a group of eight smallholders who received help from Hutan by way of interest-free loans used to set up electric fencing around the perimeter of their plantations. The fencing will not injure the elephants but it does encourage them to avoid it.

“Elephants can eat their way through one whole acre overnight, which is a lot when our land is 15 acres. The approach we took protects the farmers, protects the elephants and also collects information about them,” Ahbam says.

Ahbam has eight children, who share their father’s wisdom with the surrounding communities — people come in and out of Ahbam’s home in Sukau several times a day, chatting and seeking advice. Having only finished secondary school himself, Ahbam strongly believes that increasing the number of qualified and trained environmentalists is crucial to achieving Hutan’s objectives. “One of my daughters has shown an interest in what I do and I hope she continues with it. I don’t want my work to go to waste,” he muses. “Environmental protection is so important, and I hope more people grow to understand this fact like I do.”

This article first appeared on July 26, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.