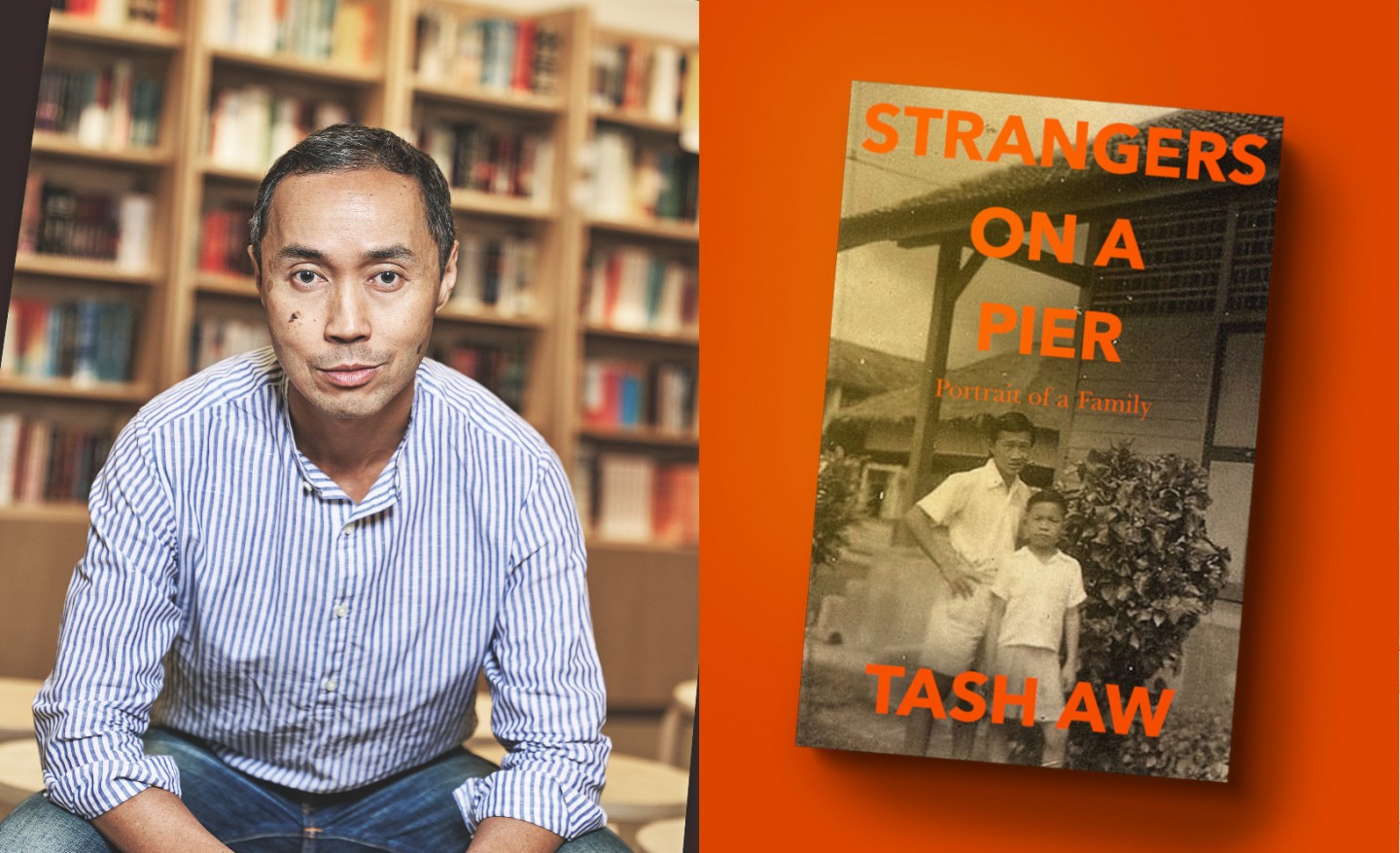

The book riffs off The Face: Strangers on a Pier, a series of short memoirs by Aw released in 2016 (Portrait: SooPhye/Book: HarperCollins)

In the lull between Merdeka and Malaysia Day, novelist Tash Aw of Five Star Billionaire and We, The Survivors fame, announced the release of Strangers on a Pier: Portrait of a Family.

If the title sounds familiar, it riffs off The Face: Strangers on a Pier, a series of short memoirs by Aw in which he explores the panoramic culture of vibrant, modern Asia through the lens of his family’s migration and adaptation. These are stories of his heritage and family history that he finds reflected in his own face, staring back at him from the mirror.

The 2016 memoir stitches together vignettes of memories, anecdotes and observations, traversing from a taxi ride in present-day Bangkok to eating Kentucky Fried Chicken in 1980s Kuala Lumpur to the treacherous boat journeys his grandfathers took from mainland China to land on Malaysian shores in the 1920s.

The slim book brims with languages, dialects and slangs mostly familiar and occasionally foreign to the local reader, painting a portrait of a region trying to find its place between events of the past and possibilities of the future. “So wise and so well done. It made me wish it were much longer than it is,” award-winning novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie remarked of The Face, and it looks like she got her wish.

Strangers on a Pier: Portrait of a Family is an expanded and updated version of the original memoir, taking a different form to share new stories and perspectives. From an airport lounge, hastily scribbled during a transit on his book tour, Aw takes the time to talk to Options about the new book as well as share his thoughts on the idea of home.

Options: What prompted you to update The Face and how does Strangers on a Pier differ from the original text?

Tash Aw: This new version takes the form of a long letter to my late grandmother — things I would have liked to say to her, things I’ve learnt over the years, perspectives I’ve gained now that I’m much older. But it’s a letter that isn’t really a letter – it branches out to incorporate the experience of living abroad, of trying to establish a notion of “home” in other places than Malaysia. I talk about my time as a university student in Britain in the 1990s, of travelling as a professional writer, of encounters that made me think of my position in relation to Malaysia.

The original edition was an extreme distillation of my thinking about several Big Ideas relating to home and belonging at the time. I didn’t have any answers then, so it ended up being a set of questions, more than any kind of solution. But I always wanted to expand on it, and lockdown – being forced to choose where “home” was – was the perfect opportunity to reflect on how my thinking had developed over the years. Friends who’ve read it say that it’s spikier in tone, angrier, but to me, both old and new editions are underpinned by a sense of melancholy, and even, dare I say it, of love.

In the time between writing The Face and Strangers on a Pier, how have your perspectives changed?

I don’t think anyone’s views on the world and their position in it could have remained static over the last five years. So much of the world has felt upended. We’ve had Trump, Brexit, Duterte, Bolsonaro, Orban, Covid, GE 14 followed by Langkah Sheraton—amongst many, many other things. Any flimsy sense of security and optimism we might have felt has been rocked in the years since. Like everyone else, I’ve been forced to confront questions of identity and belonging, of narrowing borders, even though I haven’t really wanted to. I’ve just wanted to carry on with my writing, to create art and make a living. I’m no different from anyone else in this respect. But the world changes and you have to adapt to it.

te_1078_1.jpg

Identity and belonging are key themes you cover across your work. How has your own sense of these evolved over the years, as someone with strong ties to and a life built across two continents [Asia and Europe]?

This is too big a question to answer in this interview! But if I were to attempt a highly simplified response, it would be: things don’t become any clearer over the years. I still don’t have a clear answer to the questions people ask me, such as, ‘what does home mean to you?’ I’ve just learnt to live a little more comfortably with this lack of clarity.

One of the challenges faced in trying to drive Malaysia forward is that criticism is often equated with ingratitude, as if nationalism and patriotism are the same. What do you think are the responsibilities of a citizen to their country?

Whenever I hear this question, I always feel that the question that we should really be asking is: What do you think are the responsibilities of a country to its citizens? We need to remind ourselves that a country, a state – as represented by its government – exists to serve its people, not the other way round. It’s a symbiotic relationship; love and responsibility cannot exist on one side without the other matching them in equal measure. I think the whole idea of ingratitude within the Rakyat, or indeed as applied to any individual, is outdated and doesn’t have any place in a modern, progressive country like Malaysia (or like Malaysia is supposed to be).

People often speak of citizenship and the state using parent-child language. We are said to be anak Malaysia. And since we are Asian, being a child automatically means being dutiful – it means looking after your parents, being respectful, not speaking out of turn, not criticising. I don’t think this is a useful way to talk about the relationship between the individual and the state, but even if it were, what would we expect our parents to do in return for that filial piety? Wouldn’t we expect them to be, at the very least, nurturing and protective? To be vaguely organised? To try not to constantly undermine each other? To avoid treating their children as if they didn’t matter, and to provide love and support and safety to all their children equally?

When you think of Malaysia, what immediately comes to mind and what would you like to see changed in your lifetime?

What immediately comes to mind is the most incredibly culturally rich and sophisticated country, a place and a people blessed in ways they can’t really comprehend themselves, with so much potential – and so little of it fulfilled. We take for granted so many things that others would love to possess: we grow up in what is truly a multicultural society; we have, as a result, an instinctive understanding of other languages and customs—of plurality and also of conflict, which is an essential thing to understand.

It wasn’t until I started living and travelling in other countries, both in Asia and the West, that I realised that virtually no other country has the depth of multiculturalism that we do — and that so many countries yearn to achieve it. They talk about it endlessly, fight elections over it, and yet are far behind what we have. Yet we don’t seem to realise what we have. It is this that I miss and appreciate the most – being in a place where there is a profoundly deep experience of how to live with others, even if that experience is not always happy (for how can it be?). Even in New York, the experience of multiculturalism can feel sometimes forced, sometimes mannered. Not in Malaysia. But we are in danger of losing this gift. In my lifetime, I would like to see us truly treasure it – and not just in words, pleasantries uttered amongst readers of this progressive-minded paper, but in changing political structures.

And where is home now?

Somewhere I can get rice and kari ayam. I don’t even need nasi lemak – I’m not that demanding.

'Strangers on a Pier: Portrait of a Family' retails at RM52.50 at Lit Books and at Kinokuniya.