When Lim wrapped up his last interview in 2017, he had spoken to 77 people (Photo: Low Yen Yeing/ The Edge Malaysia)

When Danny Lim was assigned by a local magazine to do a “celebratory piece” on Bersih in 2013 — by then, the movement had organised three rallies since its first in 2007 — he had his own ideas. He wanted to write about what people didn’t already know and perhaps learn something himself. How did Bersih come about? Who made the decisions? What happened behind the scenes?

Lim thought it would be enough to interview a handful of people for the article. However, each person he spoke to pointed him to someone else who knew more about the different aspects of the rallies.

The stories grew and stretched to a point where the journalist in him could see the shared histories. When people started saying, “Oh, this thing came about because they met at this period … because it was Reformasi time. It was the Ops Lalang time, that’s why they knew each other”, Bersih’s links to major events in the country’s political history became obvious. The accounts took him further back, to the radical student movement period of the 1970s, when some of these connections were made.

He knew what he had accumulated was not just about Bersih anymore. “It had become a lens through which to see Malaysian history itself and how these people [behind the movement] were linked. To some extent, how we are linked also, through this shared history.”

By then Lim, who had attended all five Bersih rallies, knew he wanted to do a book. When he wrapped up his last interview in 2017, he had spoken to 77 people. Then came the writing, which he did in spurts because of work and personal life — he became a father in 2018.

danny_lim_we_are_marching_now.jpg

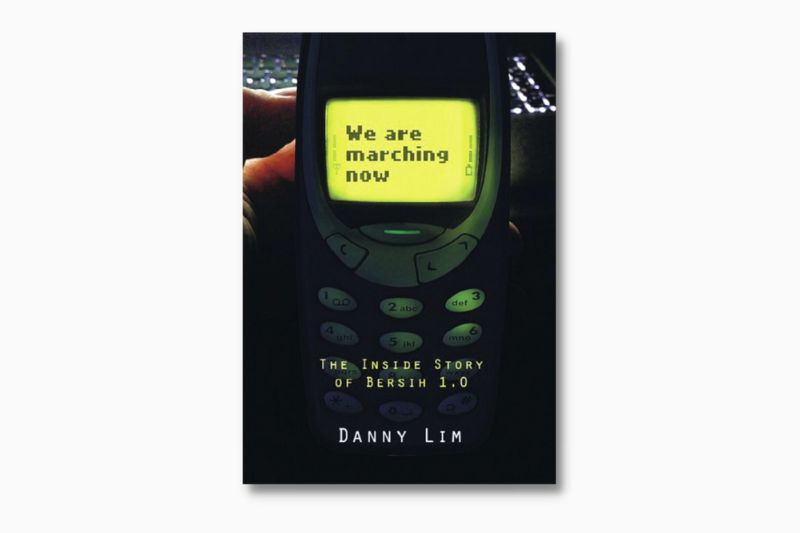

We are Marching Now: The Inside Story of Bersih 1.0 (Matahari Books) was launched on Sept 25 at Central Market in Kuala Lumpur, a meeting point of the rallies. The title is the exact message sent that fateful day 15 years ago by Bersih technical committee member Johari Abdul to project coordinator Faisal Mustaffa, two of the many protagonists behind the origin of the movement.

Many people, even those involved in the rallies, did not understand why Lim chose to feature those words, on an old Nokia phone, on the book cover. Why is the message in the dark when the rally was in the afternoon and people were out in the streets, they asked. “Well, you have to read to find out.”

He begins with a prologue that introduces bright opposition figures, multi-ethnic activists with progressive intentions who had been inspired by the Reformasi movement to join the electoral fray. But heavy losses suffered by their respective parties in the 2004 general election left them disheartened, with little to do but meet at the mamak stall below KeADILan’s old office in Brickfields, KL, to “commiserate, find solace in each other and figure out — what now?”

The book looks back on the political scenario between 1999 and 2004, from the fallout of political alliances to the decimation of various opposition parties during those years.

Bersih Zero, the next chapter, brings readers back to dynamic ringleaders who saw eye to eye and did not hesitate to form relationships that went beyond politics. People like Datuk Seri Dr Dzulkefly Ahmad, Dr Syed Azman Syed Ahmad Nawawi, Datuk Wira Anuar Tahir, Che’gubard (real name Badrul Hisham Shaharin), Mat Sabu, Medaline Chang, S Arutchelvan, Sivarasa Rasiah, Syed Shahir Syed Mohamud, Teresa Kok, Tian Chua and Dr Wong Chin Huat, who were variously in Bersih’s secretariat, or steering, technical and mobilising committees and had a hand in shaping its model.

fhntpv2veaajhvp_danny_lim.jpg

Alternative Narratives — accounts by a handful of interviewees with minimal collaboration — have been included, ring-fenced for the reader to evaluate, Lim writes. Subsequently, Mobilising the Masses and Preparing to Protest lead up to the climax, Rally Day, on Nov 10, 2007.

The author says Bersih 1.0 was led by a kaleidoscope of characters, among them politicians who were not the top-tier leadership of their respective parties, reflecting the nature of the broad-based movement at that time. “You can’t say there was one dominant personality pulling all the strings. Future iterations of the rally had faces you always saw, Datuk Ambiga Sreenevasan, Maria Chin. They didn’t really have that then. Maybe Mat Sabu, for a short period of time, but then he wasn’t really involved in a lot of other things.”

What they had in the beginning were several rings with core leaders, “not necessarily all friends now”, all fired by the zeal for change. They were similar types, though not necessarily in background, such as Tian Chua, the Melaka rice trader’s son who studied philosophy in Australia, and Dzulkefly, the kampung boy who did pharmacology.

“It helped that the political context of the time was very binary, very stark: You want change, and the obstacle to that is this big behemoth, Barisan Nasional, that has ruled for 50 years, since independence. It was like there is the big bad empire for the rebels to fight against. In that way, it was relatively easy for that zeal to be channelled in one direction, in contrast to now, [with] multiple players and multiple directions, which is far more muddled.”

History and a lot of stories have shown it is easier to fight against one big common enemy, says Lim. “It’s always after the revolution that it gets very messy.” His focus is the story behind how Bersih began, but the movement has clearly become more than that.

“You don’t bring the nation’s capital to a standstill — five times from 2007 to 2016 — with estimated (and disputed) numbers ranging from 40,000 (the first rally) to 500,000 (the fourth) protestors thronging the streets, including the grudgingly tolerated participation of a then 91-year-old ex-prime minister notorious for brutally crushing public protests, without leaving an enduring impact,” writes Lim, who had interviewed people on what they thought about Bersih 2 and 3 for the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute of Singapore, and helped cover the two subsequent rallies for Al Jazeera.

fhnxrhnucaeyx7b_danny_lim.jpg

Memory versus fact was a huge problem he had to overcome. Citing one example, he says, “I would have liked to have more quotes from Mat Sabu, but his memory was terrible — he just mixed up everything. To be fair, he has had so many rallies and all the other political stuff.”

Having a huge pool of interviews helped as he could actually corroborate what he had been told. “If three or four different people, not from the same parties, are saying the same thing, it is highly likely that it’s true lah.”

With his experience writing for a men’s magazine before working at The Sun and The Edge where he wrote for social political monthly Off The Edge, Lim consciously approached We are Marching Now in a journalistic style. “I don’t think I know how to write it in any other way. If I did try, I don’t think it would have been very good.”

He thinks he could have fleshed out certain things in the first half of the book, which focuses on the dynamics of building a movement, how political parties function or relate to NGOs, and how both relate to a mass movement. Mindful that such academic details are dry, he worried that he could lose readers there.

Nevertheless, trying to pack all the information he had gathered into one book was unwieldy, and too ambitious. So, after this volume on the first, political phase of Bersih, there will be a second, on the civil society phase.

“This is your Ambiga, Maria Chin and Hishamuddin Rais period and the tensions and compromises they had to make, especially with the politicians, who still had a lot of say.” The book will be about how the faces of Bersih negotiated that power balance with them.

As one who does not believe books should necessarily have major takeaways, Lim sees people taking what they will from We are Marching Now, from just a superficial fun read to something deep and profound.

fhnyyf0uuaeubpz_danny_lim.jpg

What would be nice, he feels, is if readers get to have some understanding of and empathy for what it takes to effectively engage in the electoral process. “It’s inevitable that you’re going to have to make very weird compromises and very odd alliances with those you cannot imagine reaching out to. And this is universal, not just in Malaysia.

“Real, tough compromises are what it takes. This is democracy, this is politics. I want people to understand it’s not so binary, not so easy. If you’re not going to accept that, then you cannot be part of the process.

“To add to that, you have to embrace the messiness. It’s going to continue, even after the election. I don’t think elections will settle everything. The messiness and uncertainties will continue.”

Has Lim ever thought of joining politics? “No disposition. I’m completely unsuitable for it.”

Can we reignite the same infectious fervour that set the streets awash in yellow during the Bersih rallies?

“I wouldn’t say never. You cannot replicate the same situations and conditions of Bersih. But as for the same zeal for change, the same understanding that you have to set aside your differences, you could see that happening again in some form. Right now is not the time; it’s just too messy. But at some point, people will be fed up and they will say, ‘Okay, we need to do something.’”

Neither hopeful nor pessimistic, Lim is philosophical. “Things have to get very bad and then there will be some form of change. I think humans are like that; they will go through these phases. The question is how long the phase and what timescale you are talking about.”

Everyone is trying to do something now, in different ways, he notes. The challenge is getting these people to redirect to at least one shared purpose, one common goal. “That’s always the far more difficult thing than before.

“There has to be new people pushing things,” he believes. Ultimately, one should remember that the older people today were the young kids, the fresh faces of Reformasi and Bersih 1.

Purchase a copy of 'We are Marching Now: The Inside Story of Bersih 1.0' for RM30 here.

This article first appeared on Nov 14, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.