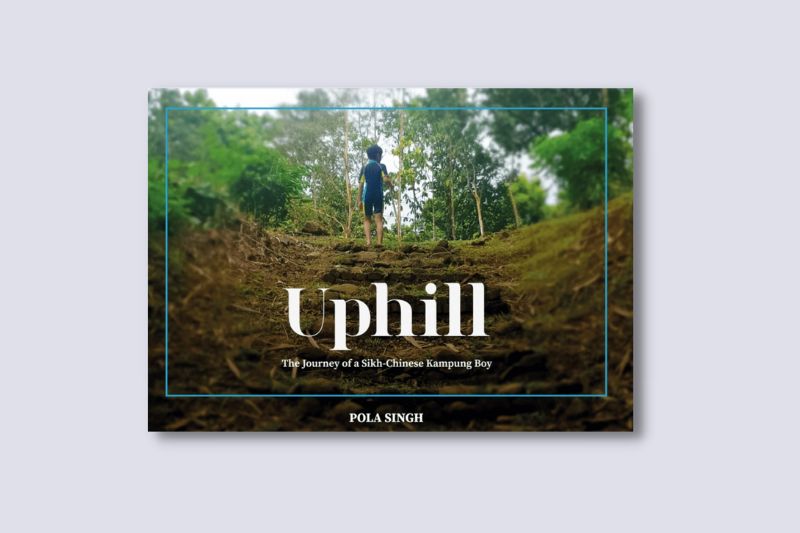

He wanted to leave a legacy for the younger generation so they will never forget how Tara Singh and Ram Kaur raised five girls and five boys through sweat and sacrifice (Photo: Anandhi Gopinath)

"What for you want to sell milk if you can go to university?” Pola Singh’s neighbours in Melaka might not have said this out loud, but they could see a better future for him and his older brother when the pair got places at University of Malaya.

Going to university was a game changer for his family as well as Kampung Ayer Leleh, where Pola and his nine siblings were born and raised. He and Jaib, the first person from their village to win a state scholarship, “broke the taboo” of impoverished kids having no chance to pursue tertiary education. Suddenly, the villagers — for whom even filling up a form was susah — saw that anyone could do it, if they worked hard.

University changed the course of this young man’s life. "I shed my inferiority complex and made new friends. I realised I was no longer the Pola Singh from Melaka. I was a new person with talent and brains.”

Pola, whose name denotes “a good man”, has certainly made good. He shares how his family made do with what they had in Uphill — The Journey of a Sikh-Chinese Kampung Boy and the brood inheriting values and a belief system from two worlds.

"My father tackled my mother because both of them knew Hokkien. But he told mum that at home, we must only speak Punjabi or Malay. My cowherd parents went for my convocation and could not understand what was going on. But they shed tears of joy.”

The Movement Control Orders imposed in 2020 allowed Pola to reflect on his humble beginnings and write this book, after his first, My Reflections of Life (2016), a compilation of articles published in newspapers, periodicals and news websites.

books_800px.jpg

He also wanted to leave a legacy for the younger generation so they will never forget how Tara Singh and Ram Kaur raised five girls and five boys through sweat and sacrifice but did not leave them a single sen. “So we didn’t quarrel. We had enough.”

Twelve-year-old Tara sailed to Malaya from Amritsar, India, in 1930 with an uncle seeking greener pastures. At 20, he was doing odd jobs in Melaka and starting to master Hokkien when he met Chan Yoke Lin, aged 13. Soon after they married, he went into the cowherding business.

Pola, 74 come July, remembers how Jaib and him, third and fourth in the family after two older sisters, had to help cut grass to feed two cows that gave them fresh milk daily.

Dad then found work as a mandor on a rubber estate in Bahau, Negeri Sembilan. When he returned home every month, Pola would help him prepare the estate’s monthly accounts. Mum was resourceful and wore many hats: factory cleaner, kutu (an informal savings and credit scheme among friends and family) leader, money lender and educator.

Movie buff Pola writes about cinemas in the 1960s and 1970s, where he enjoyed many happy hours at matinee screenings of blockbusters such as Pontianak (1957) and Haathi Mere Saathi (1971) in third-class seats. He learnt that Tamil films were always shown on the 7th and 21st days of each month to capitalise on estate workers’ fortnightly gaji and the cinema provided “momentary escape from the stress and realities of life”.

University of Malaya was where he met his wife Karina Kaur (née Leong Mei Yeen) and started his writing journey as a contributor to Mahasiswa Negara, the UM Students’ Union newsletter. After graduating in economics, he joined the PTD (Diplomatic Administrative Officers service) in 1972. A decade later, he did his master’s in business administration and then his PhD in marketing, both at the University of Alabama, the US.

In 1992, he joined the Economic Planning Unit in the Prime Minister’s Department, where he served for more than seven years. The job gave him an in-depth working knowledge of economic and social development issues that affected the nation.

After 27 years in the civil service and just before turning 50, Pola opted to retire. He then did consultancy work for a Danish energy company before joining the Initiative for Asean Integration, established in 2000 to bridge the development gap within the association and enhance its competitiveness as a region. But flying to and from the Asean secretariat in Jakarta took a toll on his back. So, after four years, he decided to take a break from work.

In 2009, just as his back improved, he was offered the post of director-general of the Maritime Institute of Malaysia, a policy institute parked under the Transport Ministry. The role involved removing deadwood and shaking up a few others in the name of change. Resistance to those measures caused him to lose sleep and he did not renew his contract in 2011.

In the chapter titled Last Lap: Final Thoughts, Pola talks about keeping fit, indulging in hobbies that bring him joy, and pursuing a cause. He co-founded Friends of Bukit Kiara, which advocated turning the expanse of the hill in Kuala Lumpur into a green lung. In 2020, parts of Bukit Kiara were gazetted as a public park, which gives it protection from land-grab attempts and indiscriminate development.

Pola wrote his first letter to a newspaper in the 1970s and has not stopped airing his thoughts on topical issues or things that matter personally. He reminisces about a siblings-only holiday in India, during which the eight of them learnt new things about each other; capturing precious moments with his two grandchildren; wearing one’s age well; and learning to make a difference in people’s lives. Folks in Kampung Ayer Leleh would nod to that.

Purchase a copy of 'Uphill — The Journey of a Sikh-Chinese Kampung Boy' for RM40 at Gerakbudaya here.

This article first appeared on Feb 13, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.