Fantasy is the genre that best suits Cho as it gives her a sense of freedom to explore the ideas she wants to explore (Photo: SooPhye)

One of the most vivid childhood memories of multiple-award-winning writer Zen Cho is that of her first day in Standard Two at SRJK(C) Kwang Hwa in Penang, after her family returned to Malaysia in 1994 from the US, where they had lived for two years after winning green cards in a US government lottery.

“You mean those lotteries were genuine?” I interrupted Cho, astonished. Growing up, I had seen them advertised regularly but thought they were scams.

“Yes, yes!” Cho replied. “Malaysia was going through some political instability in the early 1990s, so mum thought we should apply for the green card. We did, and won! So we moved to America when I was about four years old. We stayed for a few years, first in a small town near Seattle, Washington, and then in Cedar Valley, Oakhurst, California. But it was hard for my father to find work he liked and eventually, we decided to return to Malaysia.”

We were conversing at Cho’s brother’s office in Damansara Jaya, Petaling Jaya. Cho, who lives in Birmingham, England, with her husband and two young children, was on a short visit home to be with her Malaysian family over the Chinese New Year period.

Two days prior, I attended a talk she gave at Lit Books, the bookstore owned by former The Edge writers Elaine and Min Hun that is fast gaining cult status among literature lovers. Impressed, I asked my editor if I could interview Cho. Permission was granted immediately and Cho graciously accommodated me on her second-to-last day in Malaysia.

On that memorable first day at Kwang Hwa, Cho recalls the teacher confronting her in English: “Do you speak Mandarin?”

“No,” she replied.

“Do you speak Bahasa Malaysia?”

“No,” she said again, to which the teacher said, “Then what are you even doing here?” and walked off, summarily dismissing the young girl’s claim to Malaysian-ness.

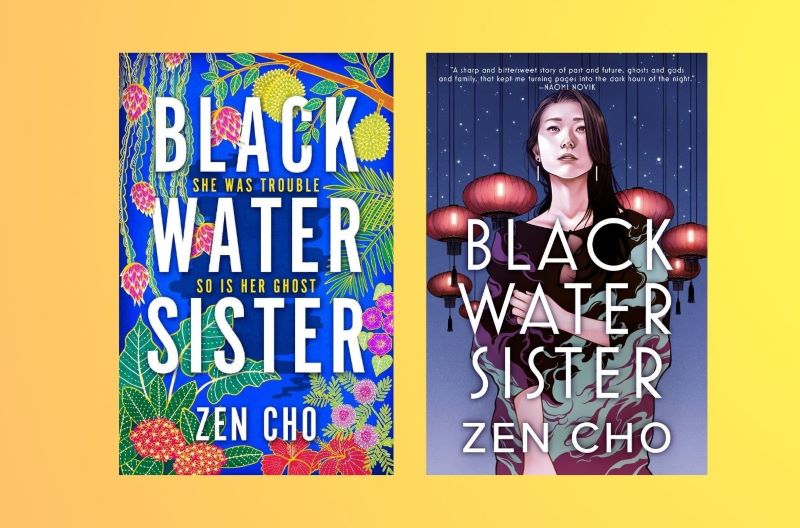

It was this incident that encapsulates some of the main themes in Cho’s books. Different though they are in terms of style and setting — her debut novel, Sorcerer to the Crown (2015), for instance, is an often uproarious historical fantasy about magicians set in Regency London, while her latest book, Black Water Sister (2021), about a woman who is haunted by her grandmother and the local deity the latter served as a medium in her lifetime, is set in contemporary Penang — issues of identity and power weave through Cho’s work like a haunting refrain. Who gets to claim or confer belonging in a particular place or society? Who gets to be at the centre of society, and who gets relegated to its margins? Also, how can the marginalised “speak truth to power” and fight for their dignity and autonomy?

The main characters of Sorcerer to the Crown, for example, are outsiders in their societies and have to deal with various forms of discrimination and oppression. Zacharias Whyte is the Sorcerer Royal, the premier sorcerer in England — but he is black in a decidedly racist country. His associate, Prunella Gentleman, is extremely talented in magic — but she is not only of mixed race, she is a woman in a society that prescribes that magic must be forbidden to women. And in attempting to stop England’s stock of magic from running out, they are driven to seek the help of another group of outsiders: a rogue band of witches on the island of Janda Baik, in the Straits of Malacca, who, led by the indomitable Mak Genggang, insist on practising magic despite being prohibited from doing so by a misogynist sultan.

In the end, in a reversal of established power systems, England is saved by one of its colonies and English society by those deemed to be members of the inferior classes.

In effect, one of Cho’s main projects, both in life and literature, appears to be that of democratising power. Speaking at the Lit Books, she told the audience that her agent in England had raised the issue of subtitling or having a glossary to explain local terms to the Western reader.

“She was very sensitive about it but it alerted me to the fact that if I didn’t have a glossary, I might lose readers. I thought about it and decided not to in the end. After all, I grew up reading Enid Blyton and the Western classics, and didn’t have a glossary. I just had to find out what scones were. Why shouldn’t Western readers have to do the same?”

It was a brave decision, and one that questions the traditional placing of English and English literature in mainstream or default position, while other literature and the experiences they describe are seen as anomalous and in need of glossaries and explanations. In Black Water Sister, Cho makes a similarly courageous decision to have her heroine, Jessamyn Teoh, be a lesbian and thus a member of a denigrated and often reviled group, especially in Malaysia, where the story is set.

“I don’t like fiction that’s too self-conscious about things like gender and sexuality, whether gay or straight. It’s only for the good of everyone if you can explore every issue of identity without fear of discrimination or recrimination. It’s only a problem if you want to shut it down or stifle it.”

Cho says the same to those who wonder why she seems perfectly at ease writing about magic and ghosts even though she is not religious but a free thinker with a Buddhist/Taoist family upbringing and has never had any paranormal experiences. As far as she is concerned, “writing stories that don’t include that magical element feels fake in a way” and “there seems to be no reason to limit my imagination only to things that can or might happen in real life”.

She also adds wryly, “I always say I don’t believe in ghosts and spirits but am a little worried they don’t care whether I believe in them or not.”

To Cho, fantasy is the genre that best suits her as it gives her a sense of freedom to explore the ideas she wants to explore. “I think it’s that distance from reality that I’m often seeking, maybe because my idea of literature, my idea of books, was something that was completely removed from real life. As a very sheltered child, there was a really big gap between my real life and what I was reading in books, and my work tries to reconcile them.

“At the same time, I really like the sense that this is a world completely separate from ours. Genre often helps create that distance, whether it’s fantasy, historical or romance. Romance takes place in a different emotional world. Even if its plot takes place in what’s purportedly our world. To some extent, this is true of all literature: it’s kind of all in its own created world, but that distance just kind of feels right to me in a way.

lit.jpg

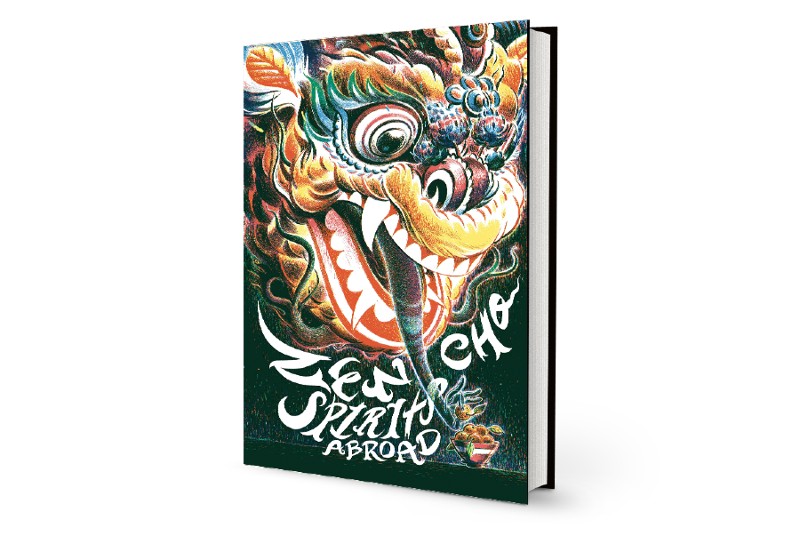

“You know, with the stories of Spirits Abroad, I found my voice. I see it as almost a lifelong project to combine the books that I loved growing up — mostly British books, with some by Americans and Canadians — and my own experiences growing up in Malaysia, and our local culture.”

Fortunately, such decisions have not detracted from the appreciation, both popular and critical, of Cho’s books. At Lit Books, she read to a packed room of people who enthusiastically peppered her with questions about her work, and the internet reveals an enthusiastic following of fans proclaiming their appreciation of her books. As for critical acclaim, among the many prizes she has won or been nominated for are the Crawford Award for Spirits Abroad, her collection of short stories published in 2014, the British Fantasy Award for Best Newcomer 2015 for Sorcerer to the Crown and the Hugo Award (widely considered the premier award for science fiction according to Wikipedia) for her novelette If At First You Don’t Succeed, Try, Try Again (2018).

Perhaps it is not surprising that Cho should be so concerned about issues of belonging and identity. Born in Subang Jaya, Selangor, in 1986, Cho and her family relocated several times before she left Malaysia to study in England at 17. Upon returning from the US, the Chos lived at an aunt’s house in Penang, where she attended Kwang Hwa. They then moved to Kuala Lumpur, where she attended SRJK(C) Puay Chai from Standard Four to Six.

Her parents enrolled her in government secondary schools, but it was still very unsettling. They lived in Damansara Jaya when she was in Form One to Three at a school in Bandar Utama, and moved to Bandar Utama when she was in Form Four and Five at a school in Damansara Jaya.

“Moving around so much made it difficult emotionally to feel at home, to feel rooted,” says Cho. “It was hard for me to make and keep friends. I read a lot. I think books became my friends, in a way.

“I read Enid Blyton and the classics. I was inspired quite a lot by these great British children’s fantasists like Edith Nesbit and Diana Wynne Jones. Their children’s books tended to have a domestic setting — it’s mundane fantasy that’s very rooted in the everyday world. That was the kind of fantasy I like reading, so it was the kind of fantasy I was writing.”

Cho credits her mother for encouraging her love of books and reading. The written word had an important place in the family and there were always books at home to provide stability because they moved around so much and her early years were “socially difficult”.

It was mum who taught her to read by the age of four and made sure she got her foundation reading classics such as Little Women and Bleak House. Penguin Popular Classics cost only RM5 each so mum bought those every week but warned her to pace herself and not ruin her eyesight. Mum also enrolled her in the KL Children’s Library and the British Council Library in her teens.

At the time, there was not much local writing and Cho, encouraged by her younger sister, took to writing fanfiction in her teens. Then, when she declared that, despite being a science student, she wanted to take English literature for her Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia, her parents agreed to pay for her tuition because the subject was not offered at her school. Unsurprisingly, she scored a distinction, as she did for all her subjects for the SPM.

spirits_abroad.jpg

On the recommendation of a family friend, Cho, at 17, left for Concord College in England, where she continued to excel academically and scored straight As in her A-Levels, which won her a place at the University of Cambridge to read law. She would have loved to study English literature but her parents felt she would have wider career options if she took up law.

“I stopped writing at Cambridge. There was so much work that I didn’t have the time. After Cambridge, I got a job as a lawyer and after a while, life was quiet. I would go home after work and had time in the evenings, so I started writing again.”

While at Cambridge, Cho met and later married her husband Peter, a British national. Today, they live in Birmingham, where he teaches 16th and 17th-century English literature and she works in a private law firm as a national product safety regulator. They have two very young children.

“So, having lived in England for the past 19 years, where does that put you?” I ask. “Do you feel British? Or do you identify as Malaysian, as a Malaysian writer? Or would you say you are more of a universal writer, who tackles universal themes?”

Cho takes some time to reflect before she answers. “I think I’m starting to feel more British now. There are still cultural differences that come up between my husband and I — you know, like in terms of food and our different tastes, what we’re used to.”

Food is very important to her as it connects her powerfully to the two countries she has strong feelings for. Her favourite foods in England are pies and scones. In Malaysia, it is wantan mee and tau sar pau.

Cho tweeted on Jan 27: “It’s tropical fruits that I really miss overseas. Everything else you can kinda get, or get a dupe of, but you can’t reproduce the mangoes straight from my parents’ garden.”

And in the next tweet, she lovingly lists the fruits she ate on her most recent trip home: “Fruits I have eaten since coming back: durian (D24), mango (harum manis), buah bacang, jackfruit (nangka), jackfruit (cempedak), papaya, rambutan, buah salak, guava, jambu air, pisang rastali.”

As for being Malaysian, she declares, “Yes, I definitely see myself as Malaysian, and as a Malaysian writer. I think belonging to a country isn’t just about whether you live there or not. It’s also rooted in the people, the food, the things you love. It’s about having live connections and relationships with them.

“My parents and two siblings are still here in Malaysia, and I keep up with the news, and what is happening with Malaysian writers, and in Malaysian literature. So yes, I identify as Malaysian,” she says in a response that I imagine reverberating back through the years to that Chinese schoolteacher who long ago dismissed her right to belong to this country.

This article first appeared on Apr 3, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.