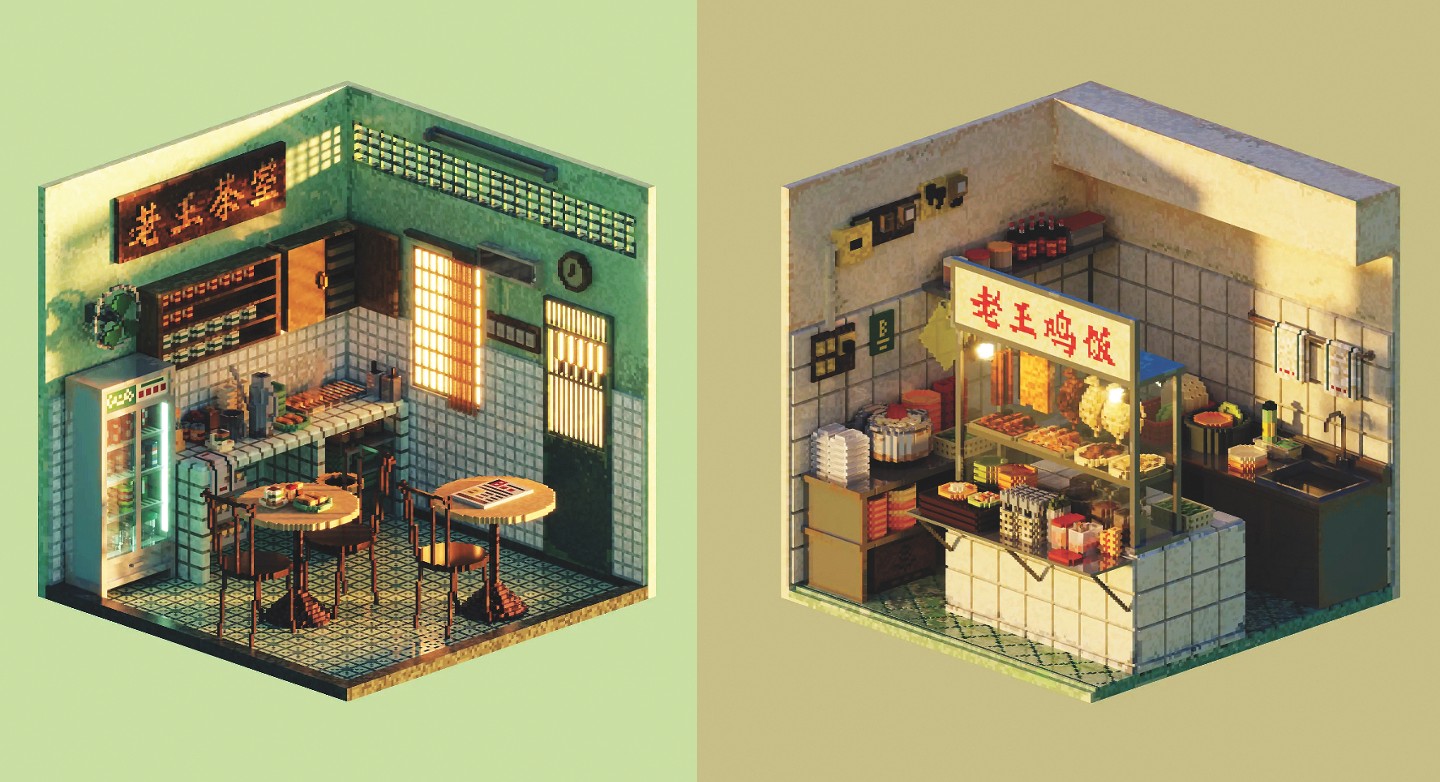

Malaysian artist Shin Oh chronicled traditional Malaysian spaces in her exhibition 126³ Tiny Voxel Shops (Photo: Shin Oh)

For many city dwellers who have fled the nest, a balik kampung trip is a chance to revisit the local haunts they will spend the rest of the year craving. Malaysian artist Shin Oh particularly misses Emporium Makan Klang, a now-defunct food court built in 1969 where muhibbah dictated the menu. But Oh and the local community which patronised some 70 hawker stalls that operated in the building can no longer return to this cherished hometown spot as it was demolished in 2019 to make way for the construction of the Light Rail Transit Phase 3 (LRT3). She has, however, dreamt up a way to immortalise a little piece of Klang for those who would like a second helping of nostalgia — through volumetric pixels, or voxels.

This digital art form stems from a computer animation technique used to generate 3D models for big names in the video game industry like Minecraft and Teardown or avatars for NFT metaverse projects like The Sandbox. Unlike the 2D version, voxel enables developers to add depth and detail to their work in the same way we used to build Lego models as children, evoking a throwback aesthetic that makes one pine for yesteryear. Such appeal dominated Oh’s art series that chronicled traditional Malaysian spaces, 126³ Tiny Voxel Shops, created for the 1,000 Tiny Artworks exhibition at The Zhongshan Building in Kuala Lumpur in 2021. All proceeds from her artwork sale were donated to Mercy Malaysia for flood relief.

market.jpeg

Awash in a moody, evening glow that lends a vintage patina, a pixelated replica of a chicken rice stall, kopitiam, tailoring shop anchored by a sewing machine and a salon complete with a porcelain sink and old-fashioned barber’s chair mimic retro shops of yore. “All of them are emotionally important to me and hold a special place in my heart,” she posted on her Instagram at @ohvoxel, which gained traction again after 126³ Tiny Voxel Shops was mentioned recently in The Guardian. “It is a project that will bring back memories for Malaysians, but also for people who have come across these old shops while travelling in Asia.”

Oh’s mother provided most of the inspiration behind her elegiac works, whose real-life visuals were carefully studied before being manifested into voxel art. What started as a therapeutic activity and hobby has turned into a creative outlet to fondly document the city’s cultural establishments, some of which have gracefully faded into oblivion under the weight of time. As our social tethers begin to fray, the sight of a vanished gem being momentarily restored transports one to an era or a milieu that will never come again.

After decades as outcasts, digital artists are receiving a warm reception at museum galleries as technology becomes a crucial collaborator. Old-guard institutions once claimed that human struggle, a quandary artificial intelligence (AI) does not comprehend or need to deal with, is crucial to the validity of artistic expression, as writers, musicians or painters face the demon of despair with every blank page or canvas. But the great irony of computer-assisted artwork is that its derivativeness is what makes it so original.

Just as Oh is keeping bygone memories vibrant and alive for a new generation with one of the humblest digital forms, voxel, a new media artist expands on the amorphous potential of pixelated art, combined with data and algorithms, on a gargantuan scale. Meet Refik Anadol.

refik_anadol_portrait.jpg

“Can machines dream?” Teased the Turkish-American tech whiz who held visitors rapt on the ground of the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMa) last November with his 3D animation Unsupervised, a mesmeric installation that ponders what supercomputers may hallucinate about after “flicking through” more than 200 years of art in the museum’s collections. Through a machine learning model known as generative adversarial network (GAN), which synthesised the archive into a digital output likened to the process of painting with data, Anadol created an ever-transmogrifying artwork of sloshing colours and shifting shapes that were projected onto a 24ft by 24ft wall.

Pixels and particles became the centre of the dialogue when Anadol brought the wild Californian landscape into Los Angeles’ avant-garde Jeffrey Deitch Gallery in his first solo titled Living Paintings in March. Across LED screens, frolicsome imagery of marine and earthen hues swirled and cascaded, translating data regarding waves, wind patterns and ecological formations from which they derive. A particular piece, for example, transformed 155 million discrete pictures of the Golden State’s national parks into a single, evolving composition. The concept of environment also extends to his other show Glacier Dreams in Art Dubai two months ago, where he raised awareness about the dangers of rising sea levels menaced by global warming in a poetic contemplation between AI and humanity.

living_paintings.jpg

Art has always impelled us to expand as well as reframe our constructs, and so too does this new terrain and medium buoyed by the borderless language of bytes and blockchains. Paintings no longer exist to be viewed from a methodical standpoint and appraised in formal terms tied to a system of financial value. Illusions that rain down on you or ripple beneath your feet are cinematic liberations of the eye designed to elicit moods, be they calmness or a sense of calamity.

Oh, Anadol and many digital custodians after them have demonstrated that it is possible to protect disappearing heritage and culture surrounding ephemerality, loss and change in a time capsule made of numbers and science. It makes sense that some of us want to find solace in the hyperreal which feels homelike and is reliably soothing in a world where so much is not.

The chicken rice stall shall live.

This article first appeared on May 1, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.