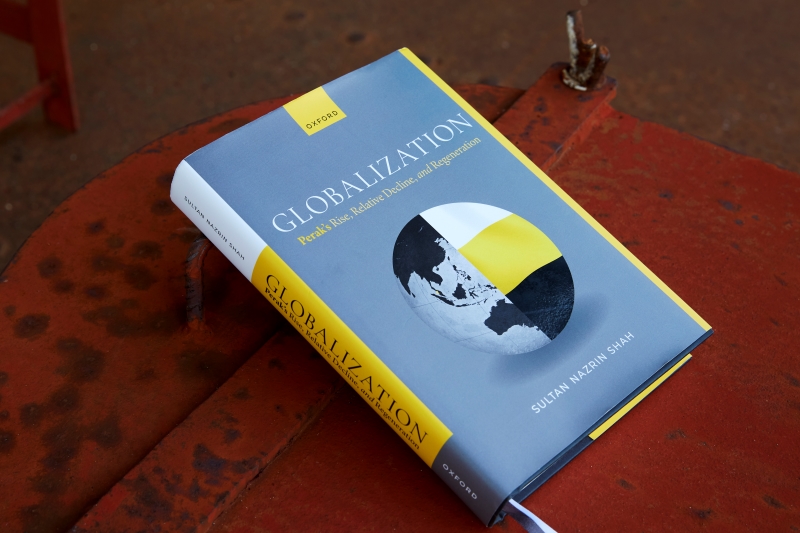

The most recent publication by Sultan Nazrin Shah academically and succintly describes the “tin trauma” on Perak (All photos: SooPhye)

Always prescient, irresistible and powerful, the “silver” state of Perak has remained most memorable, adored and appealing in the imagination of the wider public through the deft hands of our national cartoonist, Datuk Lat (Mohammad Nor Khalid).

Ipoh — once said to be at the centre of all that was chic, cool and stylish, from entertainment parks and jukeboxes to trending fashion, and nurturing some of the best mission and national schools — was captured, even immortalised, in the classic graphic novel Town Boy, especially in the evocative camaraderie between the young Lat and a Chinese shop owner’s son, Frankie, whose particularities of culture, customs and faith were rationalised and resolved in a memorable and easy conversation about pau (steamed buns).

Striking were the interior drawings of Ipoh houses in that volume, with their high ceilings, heavy ceiling fans and steep balustrade staircases, all allusions to a wealth gradually passing and climactic common sense.

As tales of many friendships go, time passes, places of importance change and relationships get lost, and it was only years later that the now-grown Lat discovers his childhood buddy Frankie, in that ubiquitous global immigrant experience of the latter half of the 20th century (and which had been the case for many a Perakian) had emigrated to Canada “in search of a better life”.

Town Boy was preceded by the even more highly praised Kampung Boy — an affectionate, if stark, gaze at that inexorable constant — change. The prescient here was captured most dramatically in the instance of the boy Lat roaming, quite recklessly, beyond the vicinity surrounding his kampung.

Straying from the inner confines of familiar streams and rivulets, he ventures to the outer “monstrosity” of the abandoned tin mine with its deep pools and gargantuan tin dredges. Stealthily, he strays into one of these imposing kapal korek — vast, motionless and devouring. A further foray into possible danger — the pits with their bottomless pools and vacant palong — is brought to an end by an encounter with a watchman guarding this abandoned mine, leading to the boy Lat fleeing to the safe confines of his home, the allegorical tension between the traditional and the modern complete.

Visceral and with a touch of the dismal, the gradual decline and eventual collapse of the tin industry — once, along with rubber, the principal natural resource of Malaya and Perak — was plainly visible to anyone driving through the Kinta Valley in the 1970s and 1980s.

Formerly bustling feeder towns — Kampar and Gopeng — once vibrant around the tin economy, still lush and green, well-treed and trimmed (the state of Perak was consistently hailed the cleanest of municipalities in all of Malaya), but now with a migratory younger population heading for the capital city Kuala Lumpur, Singapore or beyond in search of further education, better work and, in that proverbial phrase of the immigrant experience, “better fortune elsewhere”, these towns lay largely in abeyance. Smaller towns such as Temoh, meanwhile, were even left barely populated.

_s1a0382.jpg

It was such scenes that inspired photographer Eric Peris, in the 1970s, to embark on one of the most moving and significant art projects in Malaysian art history — Tin Mine Landscapes. Commenced upon the death of his father, O Don Peris, one of Malaysia’s pioneering photographers and the Royal Artist for the Johor Royal Palace in the 1920s, the series was dedicated to his memory.

Exploring, broadly, the metaphysical theme of “impermanence”, this series originally amounted to 41 images. But following the disintegration of negatives (a special curse of the tropical climate, and at once a further allusion to the notion of impermanence), only 23 survived.

Captured amid the many abandoned tin mines in the states of Selangor and Perak, the black-and-white images — meditative yet heavy and dramatic — loom against a backdrop of great historical, economic and environmental transformation.

Most interesting is a description of the trek taken by the photographer at these sites, well known for mud, silt and silting pools, where children and young men who had ventured for a post-picnic swim were later found drowned, according to the many news reports of that time.

“One has to be careful walking in tin mines” is the cautionary warning. Some areas just give way to slight pressure — mud cracks that invite one to walk further in can be dangerous. A cowherd once told me that a safe way to walk through a tin mine is to follow the trail of the cow dung. These animals do not walk into dangerous landforms. They keep well away from soft ground that would cause their legs to sink. One has to make several trips just to get a feel of the place. From one area, you have to explore other mining sites.

The images in Tin Mine Landscapes profoundly reflected the often merciless surge of economic “progress” and its cycles, leaving entire landscapes relegated to and animated only in memory, sweeping people, the environment and history aside in its relentless rush.

In the previous century, these mines, later looming ghosts in the Kinta Valley skyline, emblazoned itself on the very course of world history — even the tin helmets worn by allied soldiers in the Great War were largely made from ore derived from the Kinta Valley. And following WWII, with Europe, and Britain especially, in economic shatters, Malaya, through its commodities, was to provide almost 70% revenue to the British Empire.

After the war, erratic demand for and the subsequent lack of tin led to its diminution as a commodity. By 1985, the collapse of the tin market had induced a significant shift in Malaysia’s economic trajectory and priorities during the peak of the Mahathir years, leaving tin, and by extension Perak’s historical economic foundations, in its wake.

202333444.jpg

In Globalization: Perak’s Rise, Relative Decline, and Regeneration, the most recent publication by the Sultan of Perak, Sultan Nazrin Shah, the “tin trauma” on Perak is academically and succinctly described. “Post-Independence, Perak’s tin and rubber industries — which had largely defined its economy, population and social organisation — steadily waned, and by the early 1990s had faded into insignificance … In Perak, as elsewhere in Malaysia, tin mining companies struggled to survive, unable to cover even their direct operating costs. The state’s tin towns were economically and socially shattered, causing widespread suffering, with the loss of jobs and incomes among mine workers, their families and their communities. The devastating impact of the 1985 tin crisis hastened the demise of an industry that was already in secular retreat. Perak was on the front line of these painful adjustments.”

“Whereas a state of anarchy exists in the state of Perak” — these ominous lines precipitated the convening of the Pangkor Treaty of 1874, signalling formal British intervention in the Malay states — the sesquicentennial of which falls this 2024.

The discovery of tin, a struggle for the control of the resource and its largesse brought about an extended period of internal and civil strife in Perak. Secret society rivalry between the Ghee Hin and Hai San spilled over into the first of a series of clashes broadly termed the Larut Wars.

The first of these conflicts began over the control of waterways to their respective mines, resulting in British interest imposing a naval blockade of the Larut River. Peace ensued following the intervention of Menteri Ngah Ibrahim.

The second of these conflicts erupted following a skirmish at a gambling parlour and again elicited the intervention of Malay headmen and leaders.

By the third occasion of these clashes, Chinese secret society rivalry had spread to involve other smaller secret societies, characterised by their different ethnicities. The battles had now also come to draw the involvement of the Malay political elites, leading eventually to the struggle for the throne of Perak itself.

As increasingly common in many parts of the Malay peninsula, internal strife, loss of profit, power struggles and civil wars would elicit calls for greater “British intervention in local affairs”, and that phrase “whose advice must be asked and acted upon …” would give rise to that curious experiment in colonial rule, begun in Malaya, more specifically Perak — Indirect Rule — that would largely define the character of British administration in the principal Malay states.

202333180_1.jpg

The cataclysmic events leading to the signing of the Pangkor Treaty greatly reflected the centrality of the figure of the Sultan in ensuring peace and, most importantly, stability in the state. Central to state formation and social organisation of a deeply complex social fabric, the Perak Sultanate claimed a symbolic lineage to the figure of Iskandar Zulkarnain, as well as direct lineage to the Sultanate of Melaka.

The Misa Melayu — authored by Raja Chulan, a Perak Royal, and completed in 1908 — establishes an elaborate salasilah (genealogy) and is replete with ornate descriptions of royal marriages and the myths surrounding royal capitals, including the present royal capital of Kuala Kangsar.

Khoo Kay Kim, one of the principal historians of Perak, described the royal line: “Of the nine kingdoms which exist today, the Sultanate of Perak can lay claim to being the most ancient. Kedah could be of older vintage as a kingdom, but possibly not as a sultanate. Kedah’s early history at any rate remains shrouded in obscurity whereas it is certain that of the four ancient sultanates — Melaka, Pahang, Johor and Perak — intimately linked by kinship ties, only Perak has survived. It was the Bendahara (Prime Minister) lineage of ancient Melaka-Johor which founded the present dynasties of Terengganu, Pahang and Johor, long after the foundation of the Perak Sultanate.”

In governance, following the Pangkor Treaty, indirect rule would pave the way for other administrative experiments, including Federalism, with the state of Perak leading its implementation. In line with these administrative developments, along with the ordering of capital, Perak was ushered into — as described by Sultan Nazrin in this latest work — the Age of Globalisation.

By the turn of the 20th century, with British administration enhanced, with a new economic order and economic relations firmly established, and as tin production moved from the Larut to the Kinta Valley, Malaya, with Perak at its helm, consummated its entry into modernity. The sprouting of towns, the organisation of districts into municipalities, the emergence of Perak as an educational centre, with the Malay College Kuala Kangsar as its crest, even a blooming of sport and cultural activity ensued. The celebrated Batavian vaudeville artist Ms Riboet (Ribut) was known to include Ipoh in her touring itinerary.

At the other end of the political spectrum, Perak was to prove a meeting ground for the support of anti-colonial movements.

Sun Yat Sen arrived in search of sympathy and largesse for the Nationalist movement in China; Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, the “spiritual founder” of India, was hosted in the state capital, where he delivered an address at Ipoh Town Hall, the ideas of which would forge his well-known oeuvre Nationalism; and Jawaharlal Nehru and his then young daughter Indira, would visit soon after, rallying support for the cause of the Indian National Congress.

_s1a0378.jpg

A brief and surreptitious meeting between Indonesian revolutionary (and later first president of independent Indonesia) Soekarno and his compatriot Mohammad Hatta (who became the deputy president) with members of the Malay Left at the Taiping Runway would give birth to the concept of Indonesia Raya (greater Indonesia).

Meanwhile, at institutions such as the Malay College Kuala Kangsar and the Sultan Idris Teachers Training College in Tanjong Malim, figures such as the Pendeta Za’ba would begin to pen their anti-colonial agitations while envisioning an independent future for the Malays, in Perak and elsewhere.

The “record” has been a preoccupation of Sultan Nazrin. In 2001, he established the Economic History of Malaya project. Its purpose “was the preparation of a robust and comprehensive set of historical GDP accounts for Malaya. Data from colonial historical statistical records obtained from the National Archives of Malaysia and the National Archives of the United Kingdom were carefully pieced together using an innovative methodology to construct a time series of Malaya’s GDP and its components from 1900 to 1939.”

Two publications have since ensued — Charting the Economy and Striving for Inclusive Development — rigorous in their collation of data and statistics, establishing the trajectory of Malaya’s economic history and development.

Globalization: Perak’s Rise, Relative Decline, and Regeneration strives towards the more all-encompassing. Set against the backdrop of Perak’s economic, social and political history, the work grapples with being “comprehensive”, venturing into aspects of Perak’s more contemporary history — post-Independence federal-state relations, the effects of the New Economic Policy on Perak’s modern economic destiny, processes of migration and that contentious term, brain drain. The book ventures even into the deleterious effects of the Covid-19 pandemic upon the state and the impact of the Russia-Ukraine War on global security and supply chains.

In a contemporary local political setting that appears intractably insipid and inward-looking, the study seeks to again place the state of Perak within a greater, global scheme of things and is perhaps boldest in its stance of being anticipatory.Gleaning the present tilt of movements calling for greater social and economic decentralisation, it perceives possibilities for the state of Perak amid the present trends of deglobalisation.

202333361_copy.jpg

This, mind you, is not to be confused with ‘anti-globalisation’ as deglobalisation refers to the process of diminishing integration between states and economic chains, while creating opportunities for greater autonomy and self-reliance for communities and regions. Included are case studies in once-thriving, but later economically devastated cities such as Cornwall and Sheffield in the UK and Pittsburgh in the US, and whose lessons of recovery can be learnt for Perak. The regeneration, however, requires a re-evaluation of foundational relations. “The high degree of government centralism”, it is clearly stated, “disadvantages Perak [and other states]”.

In a chapter titled Towards A New Vision for Perak, five principles are established for this regeneration: “Ensuring efficient and transparent institutions; rebuilding human capital and increasing employability; investing in global gateways; leveraging and enhancing Perak’s spectacular natural and historical assets; and decentralising more revenue-raising and decisions-making powers to Perak.”

Much would be required in terms of policy reformulation and political will. What is firmly needed, as stated tersely in the work is, “enabling an entrepreneurial environment”.

In recent years, not unlike Penang in the north and Melaka in the south, Ipoh has witnessed a quiet surge in local economic activity. Tourism remains on the rise and cultural resources continue to garner increased interest nationwide.

HRH Sultan Nazrin’s Globalization: Perak’s Rise, Relative Decline, and Regeneration attempts to create a needed chart for regeneration at a brittle time. Less tract or manifesto, it remains not just an exhaustive and comprehensive study but also an exhortation and urging from a reigning monarch.

The book is also, touchingly, dedicated ‘To Perakians Everywhere’ — a lasting bequest from a ruler to his subjects. Beyond that, for all of us, Globalization asserts that it is ingenuity, worldliness, imagination, and that most fundamental resource of all — human and cultural — that determines, drives and animates renewal. That is the book’s affirmation. That is its remembrance.

'Globalization: Perak’s Rise, Relative Decline, and Regeneration' will be officially launched in Kuala Lumpur on July 6.

This article first appeared on July 1, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.