From left: Ts Dr Lam Sze Mun, Associate Prof Dr Norhayati Abdullah and Dr Chai Lay Ching (Photo: Harris Hassan/The Edge)

Each year for 13 years now, the L’Oréal-Unesco for Women in Science award has honoured outstanding Malaysian women scientists in various fields, addressing not only funding challenges commonly faced by researchers but also inspiring young girls to join the sector. In October last year, Associate Prof Dr Norhayati Abdullah, Ts Dr Lam Sze Mun and Dr Chai Lay Ching joined the elite group of 2,700 recipients of this annual award, which has been offered globally for the past 20 years. Selected from a pool of Malaysian women researchers and scientists under the age of 40, who are PhD holders or are currently pursuing research in any scientific field, each received a RM30,000 grant to pursue her research.

At times, awards limited to one gender can be viewed as trivialising the achievements of the recipients by narrowing the playing field or reducing competition. However, the aim of this award is to increase the number of women working in the field of scientific research and inspiring more young women to do the same. At the award ceremony, L’Oréal Malaysia managing director Malek Bekdache said, “We are not just celebrating women in science, but exceptional scientists who happen to be women.”

A similar sentiment was expressed by Prof Datuk Dr Awang Bulgiba Awang Mahmud when introducing the new Men for Women in Science initiative, which urges male scientists to contribute to a better gender balance in science. “Let us celebrate these women, not because of their gender but for what they set out to achieve,” he said.

The cosmetics and personal care company’s awareness of the importance of science can be traced back to its roots — its founder Eugène Schueller was a scientist himself. The creation of the L’Oréal Corporate Foundation, in partnership with Unesco, was in response to statistics indicating that women made up only 30% of researchers worldwide and held only 11% of academic leadership positions in Europe.

Norhayati, Lam and Chai said they do not consider the Malaysian science field to be male-dominated. Lam was happy to report that 67% of her post-graduate students are women. Chai’s experience is similar, as most of the students in her biology programme are female.

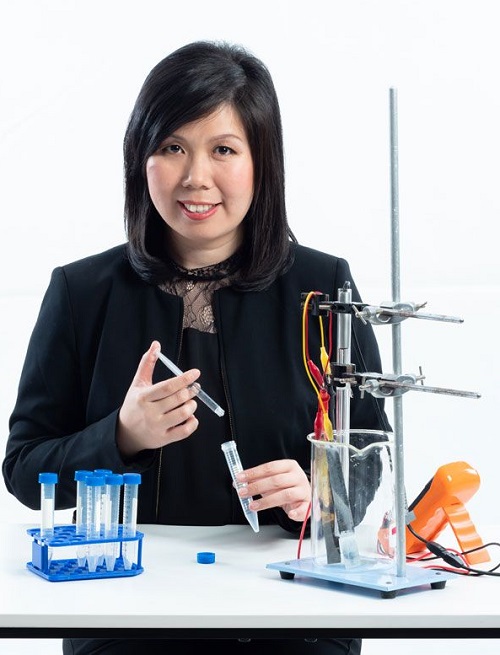

prioritise children when we have them." (Photo: L’Oréal-Unesco for Women in Science award)

“Among academicians and scientists, we do get more women. The only difference is that leadership positions are still pretty much dominated by males. The take-off time for women scientists to excel is longer than men because women tend to take time off to raise a family upon completing their PhD — typically in their late twenties or early thirties. Women face this challenge of juggling family and career and perhaps it is in our nature to prioritise children when we have them,” said Chai.

Norhayati is familiar with the balancing act that Chai spoke of, having taken a six-year break to focus on her children upon obtaining her Master’s in environmental engineering from Newcastle University. Growing up, she wanted to pursue positive psychology but when applying for tertiary education was offered environmental engineering at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) instead, an opportunity she has clearly made the best of. Since 2009, she has been researching an alternative wastewater treatment method using aerobic granulation technology that would allow for the safe discharge of palm oil mill effluent.

“I had some gender scepticism in the beginning and I was not sure about the idea of being a woman in the engineering field. I thought some jobs were more suited for one gender and that women were meant to help people … [But I have learnt] that science has no gender and is constantly changing. There are many women holding top positions in engineering companies and the water sector,” said Norhayati, who is a Fellow of the International Water Association.

“During my time, the term ‘mentoring’ was unclear and nobody told me I could do environmental psychology or environmental social sciences and focus more on the psychological part instead of the engineering part of the field.”

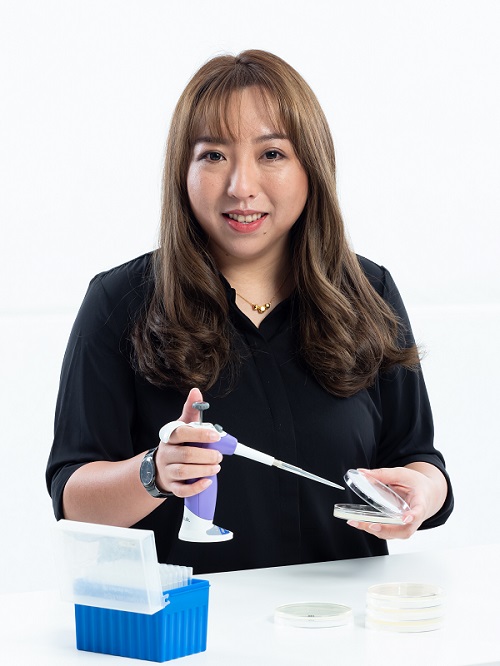

(Photo: L’Oréal-Unesco for Women in Science award)

In her role of senior lecturer in UTM, Norhayati hopes to expose her students to more career options in the sector. Her current role as an educator also allows her to tap her interest in human behaviour, interaction and psychology.

Lam, an assistant professor in Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman’s Department of Environmental Engineering, said she has always been interested in science. “I am a person who always asks ‘why?’ and I am interested to know the mechanisms of things.”

She was leaving for China the day after the L’Oréal-Unesco for Women in Science award ceremony to pursue post-doctorate studies at Guilin University of Technology. Since the end of 2017, she and her team have been working on photocatalytic fuel cell-related research that can produce clean and sustainable energy from the treatment of grey water.

“Traditional wastewater treatment only treats the water, but we can simultaneously generate electricity with it. Rural areas that have difficulty generating electricity can use this method,” Lam said, adding that while her research focuses on grey water, any form of wastewater, including industrial waste, can create similar results. “Grey water was chosen because anyone can collect and treat it to generate electricity in their homes,” she said. Her research has found that treated grey water is also secure for reuse in agriculture.

the mechanisms of things.” (Photo: L’Oréal-Unesco for Women in Science award)

Chai too developed a keen interest in science as a child. When she was seven, her father was diagnosed with kidney failure, leading her to ponder some difficult questions at a young age, such as why the disease affected her father. “When my father had to go in for dialysis, I spent a lot of time in hospitals and for a brief period, I wanted to become a medical doctor. But when I was in Form 3, I read a book on biotechnology and learnt that diseases can stem from DNA.” It was then that she became interested in biotechnology and decided to pursue it despite being told that it was not a job for a girl.

The senior lecturer at the University of Malaya’s Institute of Biological Sciences is currently working on a real-time method to detect dangerous bacteria causing food-borne diseases in raw chicken.

“The current laboratory testing for salmonella using culture is not fit for the food trade anymore due to increased volume … Testing can take three to seven days and by that time, the food is either not fresh anymore or has already been eaten. Each test also means a percentage of the food will be sacrificed and this is not economical for food producers,” said Chai, who has spent months in her laboratory sniffing out the volatile organic compounds given off by pathogenic bacteria. With further research, she hopes to develop biosensors, or electric noses, for accurate and timely detection, an effort that is made increasingly possible owing to grants such as that from the L’Oréal-Unesco for Women in Science.

To date, the L’Oréal-Unesco fellowship in Malaysia has awarded over RM900,000 in research grants to 40 outstanding women scientists, and the numbers will only grow in the coming years as will its role in empowering more women in science and research, while inspiring a new generation of girls to choose a similar career path.

This article first appeared on Jan 7, 2018 in The Edge Malaysia.