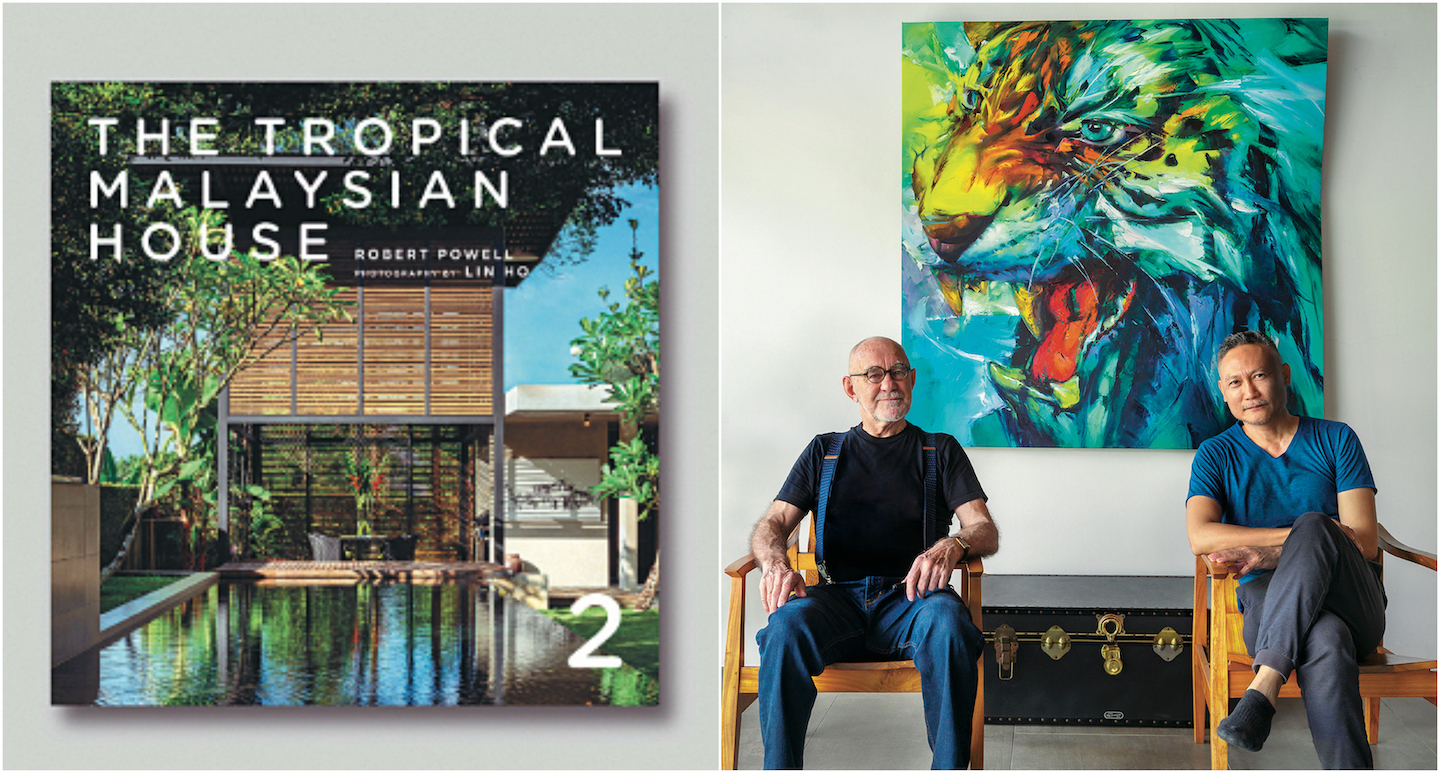

In the new book, 26 houses in locations such as KL, Penang, Batu Pahat, Melaka and Kuching are featured. Robert Powell (left) and Lin Ho collaborate for the second time (All photos: Atelier International)

Robert Powell recalls the time he first set foot in Southeast Asia. It was 1979 and the young architect and qualified planner arrived in Sulawesi, Indonesia, to help set up a wildlife nature reserve, staying in the tropical rainforest for about five months. It would mark his falling in love with “this part of the world”.

But it was only in 1984, when he returned to take up a lecturing position in the National University of Singapore, that he developed a full-blown love affair with tropical Asian architecture. During his tenure at NUS, he wrote The Tropical Asian House, which was a success. But the process of defining the “tropical house” has led to a fixation that has lasted until now, as he launched The Tropical Malaysian House 2.

“When I returned to Malaysia in 2016, I was approached by Malaysian architect Tan Loke Mun to write about Malaysian tropical houses — there aren’t enough books on the topic — and I was interested. That’s where I started,” shares Powell, who spent some time in his career working in the Middle East as a master planner. He returned to Malaysia — his ex-wife is Malaysian — when he was appointed Taylor’s University’s first professor of architecture, a position he held until recently when he resigned to fully focus on writing.

mp20.jpg

While the first book, which was published at end-2018 in collaboration with famed Malaysian photographer Lin Ho, featured homes around Kuala Lumpur and Selangor, the second volume sees the net widened all the way to the borders between Sarawak and Kalimantan.

“A reporter asked me a decade ago about what makes a Malaysian house. I remember struggling to answer that,” Powell recounts. Today, his interrogation and exploration have led him closer to an answer, where much of the insights gained have been written into the new book, he says.

Through the 26 houses featured in the second volume — the houses are in KL, Selangor, Penang, Batu Pahat, Johor Baru, Pahang, Negeri Sembilan, Melaka and Kuching — the professor has comprehensively examined not only architectural themes of topography, sustainability, ecology, materials and design but also, most compellingly, cultural influences.

“Every house tells a story, and for this volume especially, I selected houses with a strong narrative,” Powell notes. He spent hours interviewing both the owners and the architects, gleaning nuanced insights from their ethnic, cultural, religious and even educational backgrounds, and interpreting the amalgamation of influences that shape each property.

“Be it the architects, designers or house owners, there’s a rich mix. You don’t just say Chinese, or Indian, but it’s the Hakka, Hokkien or Fu Chow influence, or Sri Lankan, Tamil, Sinhalese … Even the Malays come from Bugis or Java ancestry, though interestingly, most identify only as Malay now,” Powell says, pointing out that the rich variation in Malaysian cultural identity had a unique impact on many house designs.

Ho, who once again partnered Powell for the second book, chimes in: “As we have many ethnic groups in Malaysia, it presents a great palette of inspiration for the designers to create wonderful pieces of works, be it a tiny little meditation pavilion or a huge mansion.”

boyan_heights.jpg

One of the photographer’s personal favourites is Boyan Heights, a rainforest retreat 33km southwest of Kuching owned by an Australian and Melanau couple. The distinctive gabled living area is inspired by the Bidayuh longhouse, though its height lends a contemporary touch.

Another longhouse-inspired home is the Open House II, which has a linear form. However, the rather contemporary front façade, voluminous height in the living area and other details reveal a mix of influences, stemming from its owners, who are of Chinese, American and Dayak Iban descent.

In Johor, the Cloister House’s distinctive 12-courtyard single-storey layout references Buddhist and Hindu cultures in its geometrical representation of the cosmos, taking into account feng shui elements.

The most memorable residence for Ho is Denai House — also in Johor — which is featured on the book cover. From a Western point of view, the house’s design has an entrance lobby and porch, as they were annotated when Powell first viewed the design — nothing too out of the ordinary.

new_cover.jpg

“But when the owner, who’s also the architect, Razin [Mahmood] referred to them by their Malay names — serambi, anjung and an adjoining pangkin, which is a raised timber deck found in traditional kampung houses — and explained their cultural significance, it changed the perspective of the design entirely.”

A common thread of these houses, observes Powell, is how our way of life fluctuates between the indoor and outdoor. “I always say life in the tropics takes place in the in-between space.” Ho agrees, saying, “It’s being able to enjoy comfort in a well-lit and ventilated home, despite the hot and humid weather, regardless of the size of the house.”

Noting how the tropical home is evolving organically in response to globalisation and the contemporary way of life, Powell says, in architecture, at least, one cannot force a definition of tropical houses. “You can’t lose an identity but it evolves. [That’s why] I didn’t want to look at houses built 100 years ago. I wanted to look at culture, and how that finds its way into today’s modern dwellings.”

'The Tropical Malaysian House 2' is priced at RM150. Purchase here.

This article first appeared on May18, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.