Koon with the colourful Kwai Chai Hong architecture in the background (Photo: Soophye)

Kuala Lumpur’s Chinatown is constantly evolving. Even in 2018, before the pandemic hit, cafés and speakeasies were already popping up. And while the Movement Control Orders did slow things down, it is clear that nothing can stop the palpable energy in the air.

“We call it a renaissance period right now, because it’s like another Golden Age,” says Scarlet Koon, co-author and editor of the newly released design and architectural travel guide New in the Old: Chinatown Kuala Lumpur. “Younger people are coming back and the older generation are also appreciating anew what is here right now.”

Published by Atelier International, the publishing arm of DRTAN LM Architect, this new book provides fresh insight into the area’s businesses, the restoration process behind some of the buildings and — perhaps the main draw for most Malaysians — a guide to eateries old and new. Koon and her co-authors Aw Siew Bee and Professor Robert Powell wanted the book to be very colourful, reflecting the essence of Chinatown, and so the photography of Lin Ho was instrumental in bringing the project to life.

As its title suggests, the book juxtaposes old photos of famous buildings with images taken more recently as a visual celebration of the changes the place has been through. Even the cover image includes Merdeka 118, which is still under construction and will be the world’s second-tallest building when completed, as well as old shophouses that are still being preserved. As the area is changing quite rapidly, what prompted the publication of this book now?

new_in_the_old_chinatown_kuala_lumpur.jpg

“This moment in time is very interesting, as it is right before a major change. Who knows what it will look like after Merdeka 118 is completed? So, it’s a good time to document [Chinatown] in this period,” says Koon.

As the authors wanted to centre the book on major historical roads, the tome includes walking maps spanning famed streets such as Jalan Hang Tuah, Jalan Hang Jebat, Jalan Petaling, Jalan Sultan and Jalan Tun H S Lee.

Koon says, “Roads are something that haven’t really changed much. The streets you see right now are probably the same routes people used back then. That is also why I wanted images of today and back then, to show how people lived.

“Can you imagine the old trishaws at the side and the wide roads? I really wanted this to be in the book. We also have floor plans to show how buildings were used in the old times.”

Chinatown Kuala Lumpur is split into three parts, making it easy to navigate. “First is the features section, which talks about places such as REXKL, as well as some cafés and hotels like Mingle Cafe,” says Koon. “The next part is the food highlights, where we captured all those old-timer food stalls and hawkers. If you go along Petaling Street, there are apam balik, muah chee, soya bean and Hokkien mee vendors, and all those places that have been around for a long time. Last are the historical landmarks — from Victoria Institution, a school that dates back over 100 years, to places of worship such as the Sin Sze Si Ya Temple, which was built by the famous Kapitan Cina, Yap Ah Loy. These landmarks are crucial in KL’s history. We want to capture them and tell the story because, ultimately, this book is about celebrating Kuala Lumpur itself, how it was founded and how it has evolved and grown since then.”

nito_jln_petaling_now.jpg

Koon is an assistant architect at DRTAN LM Architect and, while she has been working for only a couple of years, she has been involved in numerous projects, including some of Atelier International’s other publications. She admits that working on a book is quite a different experience from her usual architectural assignments. “As an architect whose job is mainly paperwork and a lot of coordination, you sort of sometimes forget you are a designer, or lose that creative aspect of it. But, in publishing, you get to see a lot of nice pictures and talk to a wide range of people, like business owners and designers, and then you start to feel inspired again. Seeing how people react to the publication is also very rewarding.”

As she describes her education and background, it feels as though this exploration into Chinatown was inevitable for Koon. “I studied in Kuen Cheng High School. Founded in 1908, it was only for boys back then. Later on, they started a private secondary school for girls too. It has history in Chinatown; and because it’s a Chinese independent school, we had always talked about and learnt Chinese history. Also, I grew up in KL and used to come to this area a lot,” she says.

Koon has always been drawn to the human aspect of architecture — how a space makes people feel and affects interaction. Although she had initially set her sights on interior design, her father steered her towards architecture instead. “I then fell in love with it; it’s a very different profession. It involves a lot of thinking but it’s also very hands-on, which I really like. Seeing how we can craft spaces and having that ability to create something for everyone to enjoy is very interesting,” she explains. Koon obtained her Bachelor of Science in architecture from Tunku Abdul Rahman University College and has been working at DRTAN LM Architect since.

_s1a0559_a.jpg

Chinatown through an architect’s eyes

We meet at REXKL, a fitting venue to witness the evolution of an old space into a new attraction. The building was once a cinema that seated up to 1,000 people. “I remember my parents telling me about their dates at Rex. But they avoided Chinatown for a period of time after as the area felt seedy. Recently, because I was working on this book, I brought them back here again and they were like, ‘Oh, wow, it’s changed so much. So much cleaner, so many more things to see and do.’ They think back to when they used to gather here, and how it’s still a place where they can do this again,” she says.

Now a community space with cafés, food stalls, exhibitions, performances and even a bookshop — whose massive steps once housed rows upon rows of cinema seats — on the top floor, REXKL maintains much of its old architecture. Koon points out some of the old floor tiles, mostly small squares, that were once carpeted when the space was used as a hostel, and how the first floor landing used to have a reception and computer lab for tenants. “I came here as a student and, that time, it was a very shady hostel. It was so dark and dingy we couldn’t access the main hall, so we had to climb in through a hatch underneath for a school project where we measured the space. It is very interesting seeing how it has transformed,” she reminisces. Some of the original signages still adorn the walls.

We make our way down Jalan Sultan, passing Fung Wong’s new digs. “It’s a very famous Chinese pastry shop, now run by the fourth generation. They recently relocated from Petaling Street to this new spot. Unfortunately, we couldn’t feature them much [in the book] except as a food highlight, because they just finished the renovations last year,” Koon remarks.

Chinatown is changing so rapidly that this is not the only new development Koon has seen since wrapping up the book. Still on Jalan Sultan, we spot Jao Tim (Cantonese for “hotel”) café, so named as a tribute to the guest house that once occupied the space. “There used to be a Hai-O herbal shop below Jao Tim, with its huge red signage. Earlier today, when I walked past, I saw that the shop was gone and they had taken down the signboard. Now, you can make out the original [Hwa Yick Hotel] plaque.” Koon adds that this hotel used to be a corner lot, but was later extended.

_s1a0572_a.jpg

In putting together Chinatown Kuala Lumpur, Koon discovered the difficulties and commitment required to renovate heritage buildings. “It’s not as easy as people think. A lot of hard work and planning go into restorations. Just because it’s an old building, a lot of care has to be taken for the structure and original materials,” she says. Jao Tim, for example, stripped carpets back to reveal the original timber flooring, which is over 100 years old. Because of its age, a lot of money and care had to go into conserving and making it safe. The same goes for places such as REXKL. “Only someone who is very passionate about the conservation of heritage buildings would be able to do that. It’s a commitment. Yes, definitely. So, I have a newfound appreciation for renovation work. It is different from designing from scratch where you can build whatever you want. When you renovate a heritage building, you have something that resembles a shell and you need to be able to see the possibilities.”

While food has always been a highlight in Chinatown, shoplots have changed hands over the years and the main industries have evolved from businesses such as metal works and comestibles to boutique hotels, restaurants and speakeasies. “When Chinatown started, people stayed and worked here. So, you had food, sundries and all the things you need for every day. But, as people moved out, it became a business district and, by night, it was dead. No one stayed here. Everyone was not in KL anymore, and it became very hard to access. At one point, it just became like a tourist trap, so many businesses having moved out,” says Koon.

For a long time, Chinatown was also known for its knockoffs of luxury goods and haggling was the norm, not something that would draw most locals. It was only when a younger generation of businesses began populating the shoplots again with hipster cafés and more approachable wares that Chinatown became a hub again. “I was in high school at the time, but I distinctly remember Merchant’s Lane being one of the first places to blow up. Then came the rest like PS150, Jao Tim, Mingle Cafe and then the redesign of Kwai Chai Hong. It just snowballed from there.”

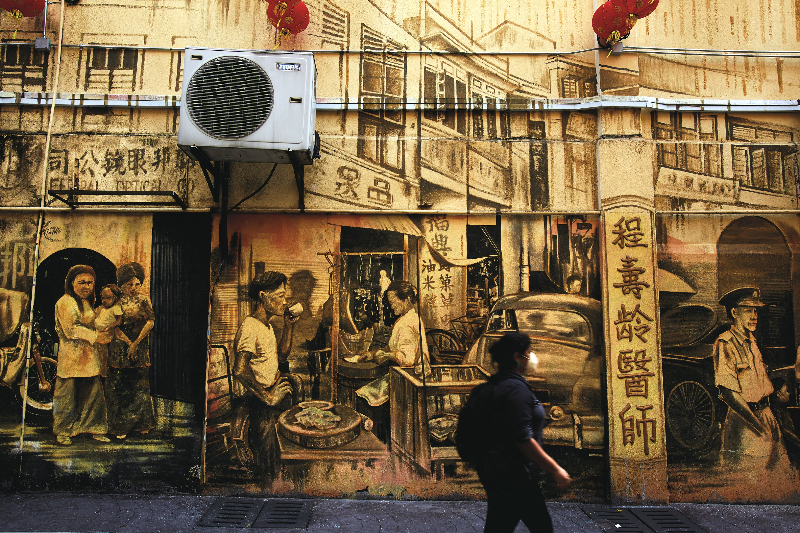

Chinatown is no stranger to murals, from iconic works such as The Goldsmith on Jalan Panggung by Russian artist Julia Volchkova to the realistic paintings on Kwai Chai Hong, but a slightly newer one titled Missing Stories of Petaling Street on Lorong Petaling signed by artist Co2_mural really stands out. Taking up the whole wall of the building, this work depicts scenes from the 1930s to the 1960s, some of which are based on old photos available online.

_s1a0599_a.jpg

We reach the end of Jalan Petaling, an area that the younger generation is very familiar with. The likes of Chocha Foodstore, Botak Liquor, Merchant’s Lane and PS150 all face the relatively new Four Points by Sheraton Kuala Lumpur, Chinatown. From here Koon points out the direction of the Kuan Yin Temple in the distance.

There are a few more noteworthy cafés and restaurants on Jalan Balai Polis. While Wildflowers is a newer establishment, Ho Kow Hainam Kopitiam has been around since 1956. Before relocating to this current spot, the eatery used to be on Kwai Chai Hong, currently an Instagrammable alleyway that leads to numerous bars and eateries. The kopitiam’s neighboring restaurant, Malaya Garden, occupies what once was an extension of the famed alleyway.

Koon says: “Not all the buildings in this area are that old; most are newer. But the history behind the people and places and how they started is all very interesting — like how they moved from one place to another and how long ago they began. For example, Ho Kow is still a family business, run by the third or fourth generation.”

Farther along the street is the famed Gurdwara Sahib Polis, built in 1898 to cater for Sikh police officers, while the bungalow-like space housing Kafei Dian on Jalan Panggong was once a post office, built in 1911.

From the hot and messy alleyway that features The Goldsmith street mural, we have the perfect view of the brightly painted yellow-and-blue façade of the Kwai Chai Hong shoplots and, rising above, the much-awaited Merdeka 118. From this spot, the old, new and in-between of Chinatown are all clearly visible. Strolling past the old shoplot façade, by local chocolatier Beryl’s, and farther along the ever-popular and modern matcha café Niko Neko, it’s easy to see how Chinatown attracts all kinds of businesses.

On Jalan Tun H S Lee, we see one of the oldest Hindu temples in the city, the Sri Maha Mariamman Temple. Founded in 1873, it was built as a private family shrine by K Thamboosamy Pillai, whom Koon notes is a major name in KL’s history. It was opened to the public in the 1920s and an expansion was necessary in 1968 to accommodate a bigger congregation. After 2002, the temple underwent renovations; as a result, the façade looks very different today. “This temple has been here longer than the Chinese Guan Di Temple down the road,” says Koon.

_s1a0703_a.jpg

This area is also occupied by the Chan She Shu Yuen Clan Ancestral Hall and three main Chinese temples: Guan Di Temple, Kuan Yin temple and — perhaps the most iconic and historically significant — the Sin Sze Si Ya Temple. Thought to be one of the oldest Taoist temples in the city, its architectural placement is only obvious from an aerial view. “If you walk along the street, it looks normal but everything is actually built at an angle because of feng shui,” says Koon.

The Sin Sze Si Ya Temple is also of great significance to the city’s history. “In the book, as mentioned by Professor Robert, we came to the conclusion that Yap Ah Loy was the founder of KL because he helped rebuild it to the point that it has become what it is today,” says Koon. “It depends on your definition of ‘founder’, right? The first to set foot in, the first to set up a building or someone whose legacy built the city. We think the founder is someone who helped build the city and really helped it to boom and this is Yap Ah Loy.

“One of the things he did was build physical markers; the shophouses and the temple, for example. Compare him to, say, Raja Abdullah or Sutan Puasa, who might have been the first to set foot in the area but left no physical markers... [they left] nothing to mark that they were here, unlike Yap Ah Loy.”

Also on Jalan Tun H S Lee is the historical Lee Rubber building, which was built in the 1930s and considered the tallest building at the time with four floors. In the 1950s, an additional level was added. Koon says this well-known Art Deco landmark will soon complete its renovations and open as boutique hotel Else Kuala Lumpur, while maintaining its historical façade.

_s1a0803_a.jpg

One of Koon’s favourite places is Warong Old China, a restaurant that serves Southeast Asian and Chinese cuisine, because, like her new book, it encapsulates both the old and new. “Johnni Wong, the owner, is a close friend and has helped us a lot. His interiors are very nice. Warong Old China’s exterior is the original and the interior is decorated with traditional wooden plaques and furniture — all from his Baba-Nyonya collection from Penang and Melaka. It is on display and done really nicely. The people who occupied the building in the past produced crockery such as plates and bowls. They were there for 80 years and only recently moved,” she says.

Nostalgic charm with all the modern amenities — that is what Chinatown has come to be. We end our tour at the iconic Petaling Street entrance marked by arches and a green roof, earning it the nickname “Green Dragon”. While it is still the go-to place for knock-off designer goods, it is also where one will find the best food stalls that have been run by generations of restaurateurs and cooks. “Chinatown is seen by many as a starting point, the genesis of their business or life in KL. Petaling Street remains the place for many to visit during Chinese New Year; for example, you can still see people queuing until midnight for the famous duck rice at dinner time,” says Koon.

Unlike Atelier International’s other books, Chinatown Kuala Lumpur offers a more human element and does not focus solely on architecture. Koon says the goal of this publication is to encourage people to see Chinatown as a place of new beginnings, enticing them to come visit. “We want more people to appreciate Chinatown. Many still dismiss it, saying ‘Oh no, the knockoff market’ or whatnot. But we want people to see that Chinatown is coming back. The charm never faded.”

Purchase 'New in the Old: Chinatown Kuala Lumpur' at RM120 from Atelier International here.

This article first appeared on Mar 21, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.