One Day I’ll Fly Away (2020) by contemporary artist Anurendra Jegadeva (All photos: Wei-Ling Gallery)

I make pictures.” This constant refrain by Malaysian contemporary artist Anurendra Jegadeva marks his person and his passion. His 2020 solo exhibition, Scream Inside Your Heart — New Paintings from Solitary Confinement, is inspired by reports of an amusement park in Japan admonishing visitors to “please scream inside your heart” — and not out loud — when riding the roller coaster as a means of reducing the risk of spreading the coronavirus. An unintentionally hilarious video shows two mask-wearing park executives, sober and stoic, demonstrating that inaudible screaming is indeed possible.

After months of being confined in our spaces watching and communicating on virtual mode, the world has had to collectively turn inwards to adjust to a new daily reality. For many of us living in confinement then, the idea of internal screaming is indeed relatable. Hence Anu has chosen to welcome visitors to his exhibition with boldness and flourish, using size and stance to present a drama of sorts on the walls, but one that is perforce restrained by the monstrosity of masks.

Venturing forward, you turn a corner to be confronted by what seems to be the core Covid 2020 collection. First, the large, looming darkness of What I Bought During Lockdown — “an ode to frivolity and self-indulgence in the time of corona”, says Anu, followed by a triptych titled Same Old Story. “In the wake of concurrent world events that eventually, and in one way or another, will affect us all …” the artist explains in the subtext to the work: the killing of George Floyd, the ensuing protests in America, the ongoing struggle of people in Hong Kong protesting new security laws, all intersecting.

In the middle stands a depiction of the artist’s daughter, representing presumably, the rest of the world, holding a huge Garuda mask over an upheld face, but also “screaming inside”. She is flanked by an American riot policeman and a Chinese security personnel, both in battle armour, brandishing the Holy Bible and The Little Red Book, respectively.

Next, dominating the walls and vision of the viewer are etched strokes, in and against bold orange and darkening greys, of Bharatanatyam dance poses. Grey Dancer 1, Grey Dancer 2 and Orange Dancer are standalone paintings in a triptych. Indian dancers are a recurring motif in Anu’s work, but this season they are wearing grotesque masks, relying only on screen-covered eyes to intimate any expression, even as they perform, blocked by no-entry bands, for a non-existent audience.

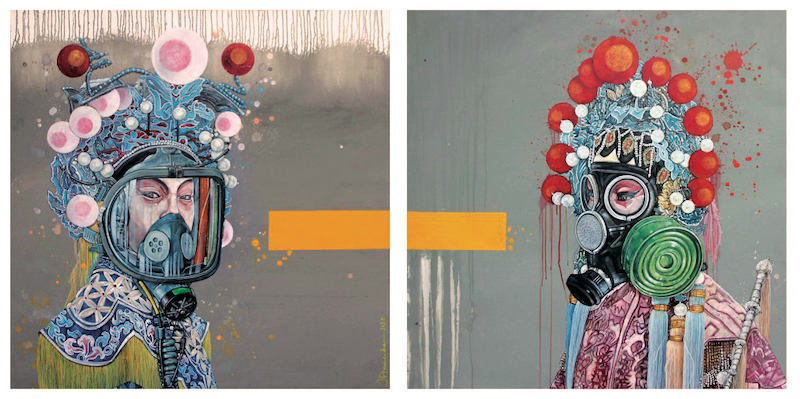

The Bharatanatyam dancers are juxtaposed with The Trials and Tribulations of Wuhan Wendy and Shanghai Sally, a very large diptych of Chinese opera performers, again a recurrent motif in Anu’s work. Here they are depicted with face shield apparatus “… within a grey imagined cocoon of silence”, says the artist in his subtext to the work — performers in pointless dress-up in accordance with the pomp and ceremony of their art, without performance or audience. Implicit here are also the Trump-ian virus allegations against China.

anurendra_2.jpg

The rest of the exhibit is a mixed bag of pre- and post-Covid works, two distinct series that Anu says reflect life before and since the pandemic. “The earlier works are relatively banal grumbles of a life-goes-on, pre-Covid world when people shook hands, shared food and even coughed in public. We got on planes, visited family, vacationed on a whim anywhere in the world … we went to the cinema, took a crowded train to work and met at bars after an unbearable week at the office.” We were bothered, says Anu, by climate change, the rich-poor divide, gender and race inequalities. We talked about things, we recycled, attended political rallies, tried not to be offended by same-sex marriage. Facebook and Instagram seemed sufficient to purge dissatisfactions.

Covid-19 and the ensuing lockdowns put everything on pause — the virtual world emerged as the only vehicle for everything, but it is also becoming increasingly insuf ficient minus real human contact. The failure of world leaders and systems is more apparent. People are dying, losing jobs and education systems are at a relative standstill. At this challenging point in human civilisation, “as an artist I simply try to describe this world I am confronted with”, says Anu. He is of the view that, in many ways, the world has been headed in this dismal direction over the last decade.

Notable among the 2019 works is Brexit Blues, an acrylic on vintage print canvas, based on the ongoing saga of the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union. A number of the 2019 works are in the format of images superimposed with mixed media detailing. He frequently uses the Queen Elizabeth stamp-head as a recognition symbol for the “fallout and impact of Empire on the world”, Anu states in subtext notes to Brexit Blues. “… in this painting she is a mere backdrop for the iconic Mercedes-Benz — using the car as the point of reference for an ironic reversal of fortunes evidenced by Germany’s amazing post-war economic and social recovery in the half century since …” He admits that in this body of work, he has relied on the absurd to lighten the loaded nature of some of his narratives.

Closer to home, Mamak Kool, 2019 promises to be a popular favourite. In this self-portrait, with a finger dipped in ink after voting and wearing a ceremonial military hat alongside a cheeky look of triumph on his face, he celebrates the election that apparently ousted national corruption along with PM Najib Razak — capturing on canvas that brief but brilliant season when the people of Malaysia undid 61 years of calcification, voting in that aging strongman Mahathir Mohamad yet again, this time as leader of the opposition, and a nation stood poised for Hope and Change.

Here, Mahathir is immortalised suited and in dark glasses; head haloed and smiling while adopting a sideways stance — just a touch of the Mollywood superstar Rajinikanth there — even as he stands surrounded by the debris of our immigrant histories, hinted at by a postcard picture of men in sarongs, songkoks and jackets, a humble plate of rice and curry, and the Chidambaram — or is it the QE2? — at the baseline of the painting, the mode of arrival in this Land of Hope beyond India, at the time.

Alas soon, too soon, “… like a perfect storm, as if a sign of things to come, in the lead-up to the terrible effects of Covid, we experienced the usual palaver and sandiwara of politics in Malaysia”, in Anu’s own words. He was a child of the Mahathir years, he says, and the leader had been a constant subject since he was a schoolboy. He has painted more than 20 portraits of Mahathir in 40 years. The large portrait of Malaysia’s again ex-prime minister — A Nation Turns its Lonely Eyes to You, 2020 — is based on a famous press image, a sad counter to the celebration implicit in Mamak Kool. Head bowed, mouth clenched, the colour grey and the heartbeat monitor showing a straight line in red, spelling the end of the nation’s love affair with Dr M, as Anu puts it.

I am drawn to the artist’s few personal pieces in the collection. Love’s Requiem, 2020 is a portrait of Anu’s daughter’s boyfriend at the artist’s father’s funeral, as he is surrounded by three generations of Tamil women, based on an archival photograph of a Tamil lady in Sri Lanka circa 1860, all posing in judgment of this Anglo-Saxon young man, presumably with some colourations of their colonial white masters. The genesis of this work, Anu says: “He was the one token white face in a sea of brown faces at the funeral. As uncomfortable as it was to introduce my daughter’s boyfriend to my old aunties from Perak, I can imagine what it felt like for him to be in the midst of protective family in their most traditional of contexts … it was very Tamil film-like.”

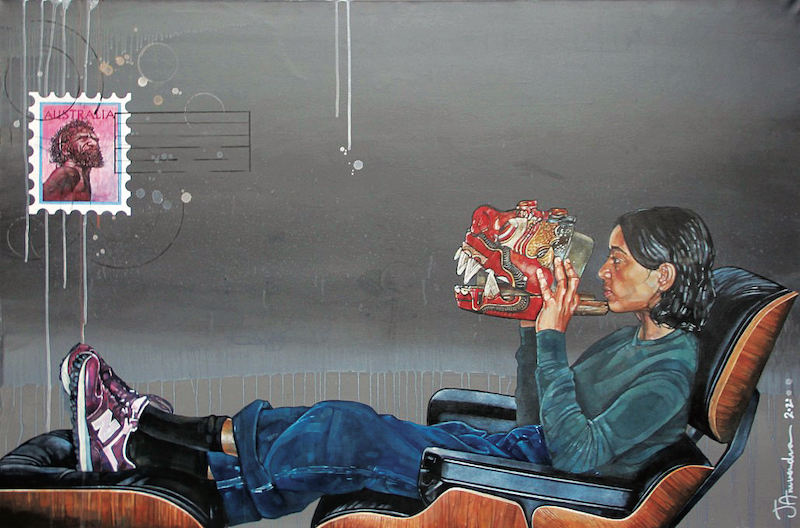

anurendra_1.jpg

Two large works depicting his daughter, Letter to My Grandmother and One Day I’ll Fly Away, both marked 2020, pose questions and anxiety for the future, for our young people. In the former, the protagonist is reclining in an easy chair, at home and in solitary confinement, looking into a Balinese mask piece, presumably composing a letter in her head to a faraway Grandma, now in a world that is again big and inaccessible, with no travel, no easy reach for relationships, “a state of limbo”, says Anu. But maybe people will write again, discover words to express depth, realities and imaginings in letters to reach far corners of the world.

In One Day I’ll Fly Away, Anu’s final portrait of his daughter, he departs from grey interiors to open blue skies, to suggest “pragmatic acceptance of the challenge of a brave new world to come”, with the simple act of wearing a mask. But the look in her eyes is of faraway resignation, even sadness, of a grappling with uncertainty. Despite the letters and the blue skies, we worry about the world our children will have to cope with.

As a creator, Anu believes people “get” his work, even the obscure signifiers, as the world around us is a common experience. As he searches for “what is Malaysian” with careful and caring honesty, he remains critical, often irreverent, but never offensive — his body of work as objective art produces an immersive and inclusive Malaysian narrative that tells our stories.

Yet despite the artist’s belief in his audience, creatives can but wish for the message in the bottle to be deciphered, and properly. As historian Farish Noor states, “We are a nation long in need of an overdue growing-up … infants in adult dress, a young nation aged before its time perhaps”. In Scream Inside Your Heart, the artist paints us an honest visual collective narrative, to view as lightly or as seriously as we choose to, or are able to. We recognise “us”, our clichés, our disgruntlement and, ultimately, our pride in being Malaysian, whether we scream it out loud or not.

'Scream Inside Your Heart — New Paintings from Solitary Confinement' is showing at Wei-Ling Gallery, 8, Jalan Scott, Brickfields, KL. Until Oct 31.Tues-Sat, 10am to 5pm. Exhibition is open by appointment only. Contact 03 2260 1106 for assistance.

This article first appeared on Oct 5, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.