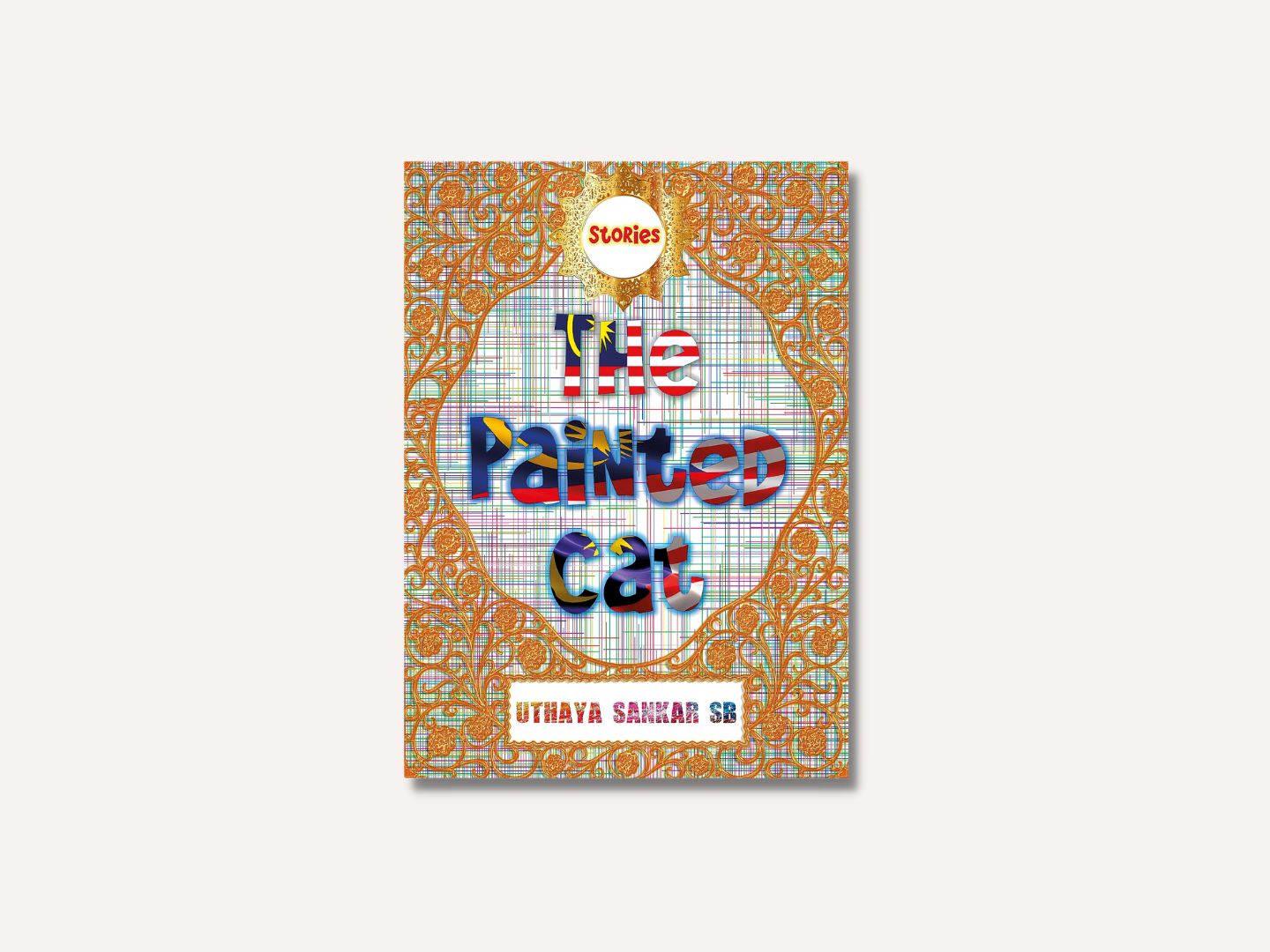

With the language barrier down, he hopes people will read and enjoy The Painted Cat (Photo: Uthaya Sankar SB)

After more than three decades of writing in Bahasa Malaysia, Uthaya Sankar S B has brought out his first book of short fiction in English. Typical of one who likes to do things differently, The Painted Cat is not merely a translation of 11 stories he has written; it is a transcreation.

Transcreators have the freedom to flex their creative muscles, adding or changing where they see fit, to shape the text for a different audience. Lalita Sinha, one of four who worked on the book besides the author himself, talks about her experience.

“A literal translation maintains the meaning of an original text at the word level. A literary translation maintains the meaning of the inherent cultural and linguistic subtleties and nuances of the original text at the word, phrase and sentence levels — characteristics of literary language,” she says.

This literary scholar, translator and critic did the latter, “to capture and convey the characteristics involving an interpretive and creative process. This requires a sufficient knowledge of both the source and the target languages and cultures, as much as recognition of the techniques and devices that are ubiquitous in literary expression”.

Then there is transcreation — translation plus creation — whereby the literary translation that has been done actually creates a “new” piece of work, not necessarily the same as the original. Changes are made to make sure it fits and reads perfectly well in the translated language, targeted at a whole new audience, compared to those it was originally written for.

“I would add that transcreation affords greater creative freedom to the translator. There is a caveat: ‘With great freedom comes great responsibility.’ Cliched, but true!” says Lalita, who worked on A Tale of Paurnami, Rebirth, and Nayagi, The Mistress of Destiny.

She chose these stories because their narratives show the mystery of connections between human existence and the divine, subtle or spirit realms, topics she is interested in. “This [English] version is also a first in the sense that the stories have been purposefully transcreated.”

edge_uthaya11.jpg

Rebirth deals with divine incarnation and human reincarnation. Paurnami is of a cosmic nature and draws the reader to ancient myths and beliefs about the human connection with the moon. Nayagi, which Lalita was commissioned to translate for a different publisher in 2009, looks at a person’s struggle with forces beyond her control, her fate or destiny.

Nanthini Muniapan, a seasoned IT professional with a keen interest in Indian mythology and folklore, transcreated Grandpa and the Moon for the collection. K Pragalath, a writer who works as a copy editor at the news website Harapan Daily, handled An Epic Ride. University of Technology Sarawak lecturer Roshini Muniam took on New Year’s Prayer. Also a corporate trainer and language consultant, she believes everyone has a story to tell and translation allows stories to travel.

Uthaya transcreated five stories: the titular piece, An Ordinary Tail, Strange Things, Datuk Came to Siru Kambam and The Migrant Gardener. This author, who writes because “I don’t want to forget the simple moments in life”, includes an illustration for each piece, to give the eyes some rest.

He closes The Painted Cat with The Origin Story, a chapter explaining how each of the 11 stories came about, why he wrote them and their journeys to the page or prize after he was done.

Lalita, a retired lecturer now also into creative writing, has been reading Uthaya’s work since the early 2000s. His style, though simple, often requires the reader to reflect further before the full significance of the stories is grasped, she says.

“Writers are at liberty to choose not only in what language they write or translate but also why. To address the ‘what’ as I understand it, when Uthaya chose to write the original stories (and most of his writings) in Bahasa Malaysia, he did so deliberately — to make a particular statement. It is to maintain his right as a Malaysian writer to express himself in the national language of Malaysia — distinct from bahasa Melayu, the language of the Malays.”

Lalita adds that having this collection out means the author can reach a wider, English-literate audience. “I believe the book provides interested readers with not only access to the originating stories but also an informed knowledge of their wider cultural environment. This is an integral part of the stories, the author’s identity and a part of the Malaysian identity.

“I see Uthaya’s contribution as an additional ‘dimension’ to Malaysian literature, which so far has existed as two discrete modes. The first, our national literature written in the Malay language, is supported by the state; and the second, Malaysian literature in English, is contributed by individuals. By moving between Bahasa Malaysia and English, he has initiated a presence in both.”

lalita_sinha_transcreator.jpg

What did she pay close attention to when interpreting the stories?

“Interpretation involves dealing with multiple layers of meaning that are not only grammatical and semantic but also nuanced, arising from a specific culture: its society, language, history and tradition. These elements have to be negotiated when conveying to another culture, concisely and precisely, without damaging meaning in the original text.”

Will The Painted Cat, self-published with the help of social contributors, seem irrelevant to some readers because it has pieces set in a specific time and place?

“Works of art, including literary works, have the potential to alienate and manipulate, or connect with and liberate, the audience. A work does not exist in a vacuum. Thus, its relevance is determined not only by time but also by the place, conditions, experience, ideology and so on of the readers. So, the question of relevance lies with the individual,” Lalita thinks.

Magic realism, a historical feminist melodrama, big shots and pomposity, complicated familial ties, community and a sense of belonging, and beliefs peculiar to the Indians in Malaysia are threads in the stories. Did the last make her work more difficult?

“I think it is neither the translator’s task, nor possible, to ensure that the emotive impact [of a story] on one ethnic group is the same as, or of relevance to, another. Rather, her task is to be attentive and faithful to the original text, with the purpose of achieving an accurate representation as far as possible. [Academic, writer, editor, translator] Mohammad Quayum, an authority in the field, describes this as an ‘excruciating’ process. At the same time, it is richly rewarding to achieve a close representation of the original. So, yes, in this sense, the process does become more difficult.”

Uthaya did not choose the stories for any particular reason. What he did was draw up a long list of those suitable for pembaca umum (general readers) then let the transcreators pick which they wanted to work on.

From the very beginning, he told them they could make minor changes so that the stories read better in English. When the manuscript was sent to Amir Muhammad (the editor), he, too, had the liberty to do the same.

“It was all done deliberately as part of the transcreation process. In Malaysia, we are more familiar with translation, but I really prefer transcreation, which is nothing new in media, films and literature overseas,” says Uthaya.

Neither did he set a theme for the collection. “It was more of ‘the best of’ Uthaya’s stories chosen by the readers and transcreators. The end-product, when I read and reread the manuscript for the completed book, shows how children tell their version of what they see happening around them. Kids seem to be the main storytellers in many of the stories in this book.”

He started telling stories early too. Nayagi was written in 1991/92, after which the then-19-year-old sent it to Dewan Siswa magazine. It did not get published but he came to know about the Hadiah Cerpen Maybank-DBP (Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka) contest. He sent it in and won the first prize.

During that time, he wrote a number of other stories. One for children, titled Ayya, was his first to get published, in Dewan Pelajar.

As an Indian who insists on writing only in Bahasa Malaysia, he hopes those who have never picked up his books — there are more than 20, the first was published in 1994 — because they are not proficient in the language can now do so.

“I want them — Malaysians and non-Malaysians who are not familiar with fiction in Bahasa Malaysia — to know that Malaysian Literature is not only about Malay characters, Malay culture and written by Malay writers. Sad to say, DBP and ITBM [the Malaysian Institute of Translation and Books] tend to present (in translation) Malay Literature (Sastera Melayu) by the Malays, about the Malays and for the Malays as Malaysian Literature (Sastera Malaysia) and National Literature (Sastera Kebangsaan).

“Of course, we have many wonderful Malaysian authors writing about the real Malaysia in English. But the translated works are very much Malay-centric. So, I want people who have not read stories in Bahasa Malaysia to know that this is what Sastera Malaysia and Sastera Kebangsaan really is — not just oleh Melayu, tentang Melayu, untuk Melayu.”

(A Bernama report dated March 12 says DBP is devising the best mechanism to ensure the RM20 million allocation to be given by the government through Budget 2023 will also benefit publishers and help the country showcase quality translated works. Issues that DBP will focus on include the translation of original works and masterpieces in the Malay language into foreign languages and vice versa, as well as the publication of masterpieces and selected publications.)

Uthaya is pleased with how the transcreators stayed true to the spirit of his original stories, often reading them many times to fully understand the context. One even listened to an audio recording of a story he did in 2017 for the visually impaired to get the tone he used to present it.

He started primary school nine years after the medium of instruction had switched to Malay. But the teachers were still using lots of English and he had the benefit of both.

“My thinking process has always been in English. So, all the Bahasa Malaysia stories, including the dialogues, I have written were actually thought out in English and then transcreated into Bahasa Malaysia. I must say the English versions by the transcreators are very much like my original ‘thought’.”

With the language barrier down, he hopes people will read and enjoy The Painted Cat. Support will motivate him to start working on another collection with the same team but more transcreators.

“I want my books to involve as many people as possible — transcreators, editors and social capital contributors. I want the book and the project to be ‘our project’.”

This article first appeared on July 17, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.