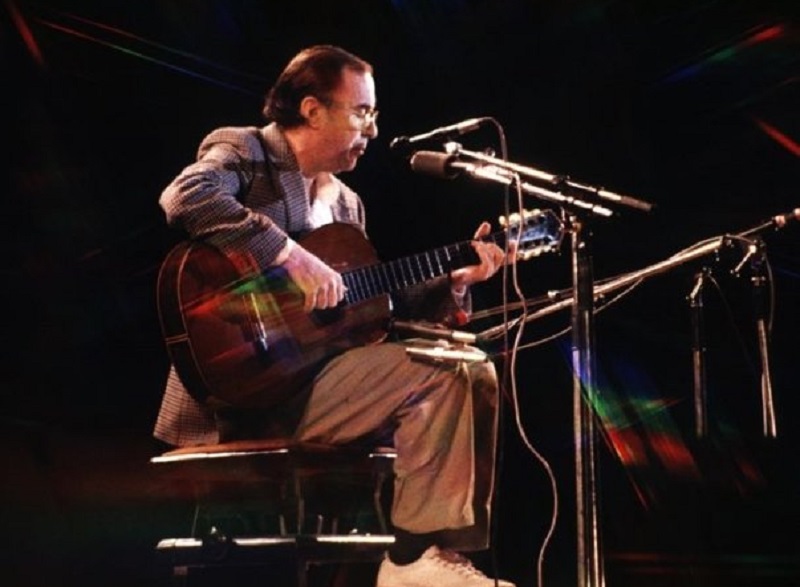

Gilberto is the pioneer of the musical genre of Bossa Nova in the late 1950s (Photo: EPA)

By the mid-1950s, emerging from a length of political volatility dominated by extended periods of military rule, the people of Brazil voted to office one of the most popular and progressive presidents in its history — Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira. Campaigning on the pledge of delivering “fifty years progress in five”, JK, as he was popularly known, set out a series of policies that ushered in one of the most economically prosperous, politically liberal and stable periods in Brazil’s otherwise tumultuous history.

This rapid pace of progress was marked principally by the creation of the landmark administrative city of Brasilia, which was planned and designed by, among others, the legendary architect Oscar Niemeyer.

For a while, it seemed nothing could go wrong: the prosperity of public life seemed to permeate fluidly into Brazil’s variegated social fabric. It was a period of the greatest achievements in the arts, literature and experiments in film. Brazil’s unique sensuality — marked by the new curvaceous architecture of Brasilia — appeared to flow freely into all realms of its distinctive culture.

joao.jpg

By the time the Brazilian football team won the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, with an array of imaginative, wizard-like players who gave new meaning to the term “the beautiful game” and possessing such sultry names as Vavá, Didi, Garrincha and Pelé, it seemed Brazil’s period of Greater Carnival would never cease. It was an epoch marked by sophistication, sensuality and seduction, and for all that was being born and reincarnated, it seemed that even the Samba — the sound of the Carnival, the classic music of the African and South American crossroads — would have to be renewed.

In the late 1950s, two men sat in a snack bar on Ipanema beach in Rio de Janeiro, watching a delicate Delphina (beautiful girl) walk by. That girl — Heloísa Pinheiro (later one of Brazil’s best-known models) — would give birth to a song that encapsulated the breeze that was the Brazil of that age:

Quando ela anda ela parace uma sambista

Que balanca tao bem e agota tao gentilmente …

When she walks she’s just like a samba

That swings so cool and sways so gentle …

One of those men was songwriter Antônio Carlos (Tom) Jobim who would go on to unfurl a musical sensation that seized great parts of the world — from the sounds of jazz in the US to the cabarets of Southeast Asia, the smooth musical style of Bossa Nova was born. And the figure that carried that music across these borders and continents was an intense, deeply introverted figure, João Gilberto. He would go on to be known as O Mito, the legend.

It is difficult to imagine today — as the ubiquitous rhythms of Bossa Nova grate in elevators and elsewhere — just what this sensual revolution meant. It gave new meaning to the term “cool jazz” and unravelled new possibilities in musical form and attitude.

In the 1960s, as the US, and much of the rest of the world, was literally going hysterical to the sounds of the British Invasion — the Beatles and the Rolling Stones in particular — another mood and another kind of personality was seizing the artistic imagination.

By the late 1950s, Gilberto had begun to refine the sound of Bossa Nova. Never principally a songwriter himself, he cleaved off the songs of others, creating a distinctive impression on them that was wrought of his highly attenuated sense of tone and his fastidious perfectionism. His first album Chega de Saudade blazed through Brazil and gained a curious, if critical interest, in other parts of the world. Moody, introspective and lyrical, it captured that distinctive sense of melancholy contained in that most untranslatable of words or attitudes, saudade.

Whisperings of a “new sound” from the South drew the attention of the saxophonist Stan Getz, who borrowed the sound for several albums before recording, with Gilberto and Gilberto’s then-wife Astrud, the classic Getz-Gilberto album. Its popularity and influence was immediate. Its influence on American jazz was revitalising.

It inspired an entire generation of jazz players, including guitarist Charlie Byrd and Quincy Jones, to adopt the form, and it even gripped the attention of popular music. All of this culminated in the first North American concert of Bossa Nova at Carnegie Hall featuring the lights of the genre — Antônio Carlos Jobim, Luiz Bonfá, a young Sérgio Mendes and, of course, Gilberto.

The event proved a watershed experience for the musician from the region of Bahia — known for its sugar cane plantations and painful history of slavery. But even as the years of struggle as a musician ended, other struggles began: In 1964, as Getz-Gilberto gained unprecedented acclaim and success, Brazil’s period of Greater Carnival came to an end as a brutal military coup ended years of civilian rule.

Gilberto chose to live in exile even as his music, ironically, inspired a new generation of radical and politically driven artists, including Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil and Naná Vasconcelos, the wild man of Brazilian music. Remarkably, this generation of artists — so different in their musical posture and attitude — paid great homage to the smooth Gilberto. Listening to Gilberto was “like enlightenment for me”, Veloso said. “It was like an incredible revelation of everything, of aesthetic criteria and deep emotions, and most of all, hope in Brazil … Hope in our future and the idea that we had a kind of mission. I still think Gilberto is our greatest artist.”

Throughout this time, Gilberto remained a deeply reclusive, introverted figure, regarded as mildly eccentric for his deep love of cats. For all that Getz-Gilberto was, his later solo albums — Amoroso, João Gilberto and João, in particular — forged the deepest and most intense impression, marked by the adventurism and perfectionism that made Gilberto the admired and intriguing figure that he was.

The later years proved especially difficult for Gilberto as he grappled with family troubles and financial difficulties but upon his death on July 6, at the age of 88, the outpouring of veneration and love seemed to vindicate his isolation and remoteness as being those very qualities that made him and his music distinctive and exceptional.

The confluence of open chords, poetry and the expansive tone were the hallmarks of a Gilberto song. The moodiness, intensity and introspection, its spirit. In the words of Miles Davis, “João Gilberto on guitar could read a newspaper and it would still sound so good.”

Eddin Khoo is the founder-director of Pusaka, a non-profit organisation that works to support the continuity and viability of traditional performance arts in Malaysia.

This article first appeared on Jul 15, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.