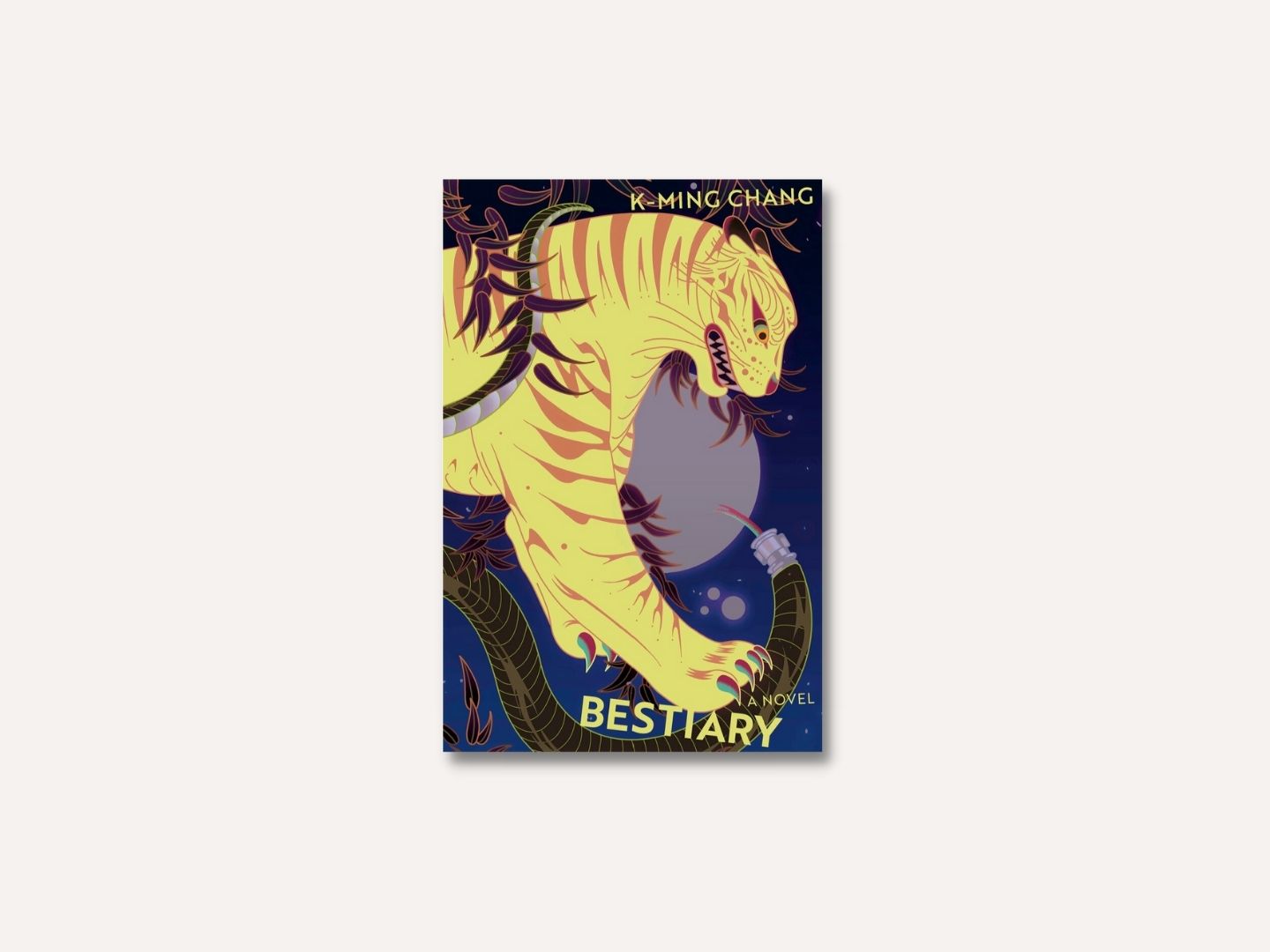

Cover designed by Suzanne Dean and illustrated by Jinhwa Jang (Photo: Harvill Secker)

In the first chapter of K-Ming Chang’s Bestiary, I got the sense it would be similar to C Pam Zhang’s How Much of These Hills are Gold, about a diasporic family’s survival and hunt for gold. But I quickly found that I was very wrong. Chang’s debut novel fits firmly in the genre of magic realism, folding in mythical stories and fantastical moments that physically manifest in her characters’ lives. It is so apparent that she is a poet. Every paragraph is coated, made heavy with vivid imagery. They are sharp and precise, as though carved with the precision of a chef’s knife, and at no point can you predict the magic Chang is trying to bring to life.

Spanning the perspectives of three generations — the unnamed grandmother, mother and daughter — of Taiwanese-American women, Bestiary explores tales of mythical creatures and stories that bind these women together. While there are multiple stories that transform Bestiary, the tale of Hu Gu Po, a tiger spirit that inhabits a woman’s body and sustains her form by feeding her hunger with children (especially their peanut toes), is one that sparks pivotal change. The daughter grows a tail, and believes she is the conduit for the tiger spirit. More mysterious happenings follow, each linked with tokens of wisdom or fantastical myths from mother and grandmother.

Very early on we learn that “Orientals don’t sweeten tea. Don’t sweeten anything. We prefer salt and sour and bitter, the active ingredients in blood and semen and bile. Flavours from the body”. In Bestiary, the body is a focus, from ablutions and excretions to physical pleasure and pain. Sensations such as pain are even more so emphasised. For instance, while grandmother cannot tell the voices of her daughters apart, she hits one and says she knows them by the sound they make in pain.

k-ming_chang.jpg

In each chapter, the voices take on a new vehicle of imagery. These pictures travel from Taiwan to the US, recalling myths of the women’s motherland and applying it in their new home, from gold and the idea of burial equating to birth and death; milk and the temporality of teeth; as well as bruises and bones. The symbolism, while seemingly ever-changing, actually develops with each chapter.

Just like poetry, Chang’s prose is not encumbered by the rules of punctuation, and we see dialogue in italics and grandmother’s letters with gaping holes and words scattered on the pages. “All voices have wings, she said, that’s how they travel.” Delving into familial relationships, love and inherited trauma, the novel jumps between the perspectives of the three women, from the moment of birth (and the magical means of their conception) to their tenuous relationships, especially with each other.

Bestiary tries to capture the essence of ever-changing oral myths and stories, interjecting different versions and interpretations. It almost re-enacts how stories travel by word of mouth, in an almost cyclical fashion that transforms with each new generation. From the grandmother, to mother and, finally, daughter, Chang gives the reader individual perspectives. “My mother’s version” versus “my version”, and even in some sections the daughter admits that her own memory of a tale cannot be 100% relied upon, and instead gives her mother’s account of events.

When trying to decode her grandmother’s letters, the daughter says, “In the water, the words thrashed, like fish, stilling only when I said them aloud”. These magical myths only ever “still”, the same way poetry and performed stories only ever make listeners stop, when they are said aloud. Their performative nature brings them to life, but once the voice stops they are open to interpretation and change. Bestiary is both myth and perspective, and creates an incredible dialogue between the two.

It is not an easy tome to consume. It’s heavy with meaning and myth; each unravels truths, none of which settles or sits still. Towards the end I felt the myths and fantastical elements were too bizarre to fathom, but there was still something quite revealing about how linked the women are, and continue to be. The daughter says, “My right hand is inherited from my mother and my left one is descended from Ama. Neither was mine.”

And is that not how we all feel? Inherently defined by those before us. But what the daughter says after holds some truth: “But Ama didn’t know my third hand, my tail, honed for this night.” Perhaps we have something that is all our own too.

K-Ming Chang's 'Bestiary' is RM79.90 at Litbooks. Buy here.

This artice first appeared on June 21, 2021 The Edge Malaysia.