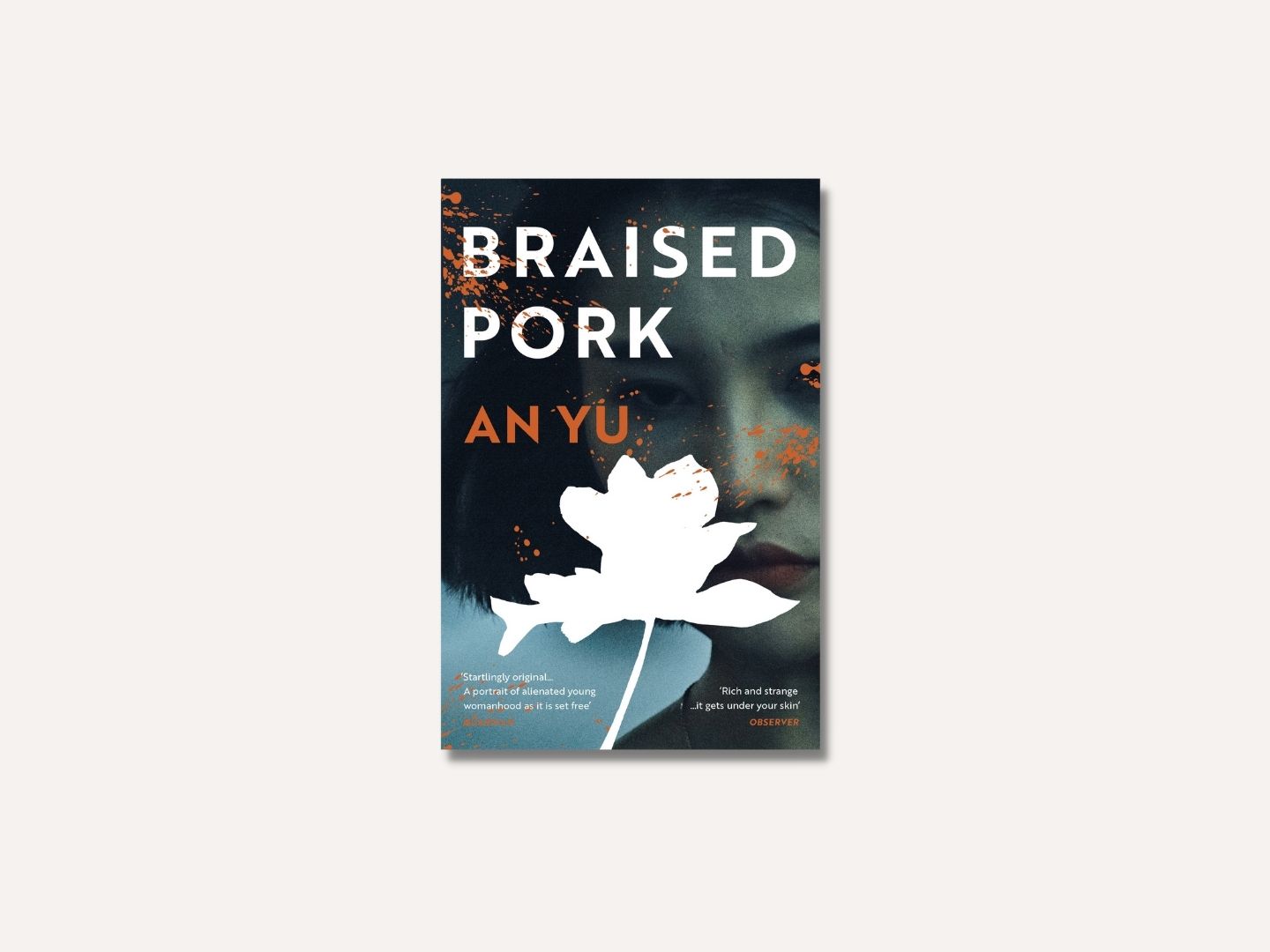

An Yu’s novel is dreamlike and surreal, but it is also filled with realistic characters with tangible and relatable emotions (Photo: Vintage Publishing)

From the moment we meet her to the end of the novel, Braised Pork’s protagonist Jia Jia is always searching. Searching for her next step, for meaning and for answers behind the sketch of the face of a man with a fish body next to her husband’s corpse. At the very beginning, she is confronted with his body floating face-down in the tub in their Beijing apartment, a harrowing incident that launches her into a journey of self-discovery, one fraught with heavy emotions and numerous unanswered questions.

An Yu’s novel is dreamlike and surreal, but it is also filled with realistic characters with tangible and relatable emotions. As Jia Jia learns to navigate her new independence and reawaken the part of herself kept dormant to keep her husband happy, she falls for Leo, a barman, and soon after enters another world where air is replaced with water, and the fish-man makes itself known to her. After awakening from this frightful place, Jia Jia revives her love and talent for art — an ambition her husband had insisted she demote to a hobby — and attempts to paint the fish-man, always stumped when she comes to its face. It is at this point that she decides to take a journey to Tibet to trace the origins of this haunting creature.

an_yu_.jpg

The first mention of braised pork comes when Jia Jia has lunch with her distant father. She looks longingly towards an elderly couple at another table, enjoying this popular dish. Between their small talk and companionable silence, “she saw something that she did not have”. For most Asians, braised pork is a familiar dish, reminiscent of home and family meals. For me, even the name of the dish triggers the memory of a sticky, salty, sweet sauce clinging to juicy pork belly, with the perfect ratio of fat and meat. For Jia Jia, it represents a longing for something that she still cannot put her finger on. However, when braised pork makes a reappearance later in the novel, the truth behind all the mysteries is revealed.

Jia Jia reflects on her repressed nature and sense of melancholy, littering her thoughts with snapshots of half-remembered memories of her mother and family. What is curious is how only men seem to have a noticeable impact on Jia Jia’s being — from her dead husband and Leo, to her father and Ren Qi, a writer she meets. Unlike the protagonist, the rest of the women in Braised Pork lack active participation. Her close friend helps her move and then disappears, her grandmother shuffles about her own business, and her aunt is preoccupied with her husband’s arrest. Only her mother is boisterous and adventurous in her memories, the sole person who has made a mark on Jia Jia.

Throughout the novel, Jia Jia’s relationship with water evolves, mirroring her understanding of the mystical “world of water”. When trying to paint water, she feels that “there was something about the movement of the ocean and the semi-translucency of the water that she could not grasp; some balance between mystery and simplicity”. Later, she tells Ren Qi, “I’ve always been fascinated by things related to water but I’ve also been a disaster at painting any of them. Maybe I’m just setting myself up to fail”.

Right before the pivotal point, where all is dislcosed, Jia Jia cries. Her heavy tears make her feel as though she is “shrinking down like a bar of soap”, but what actually shrinks are her uncertainties. Losing water (her tears) has a restorative effect, as though she has released her woes. An Yu really drives home the idea of water being this murky veil that represents Jia Jia’s unknown past, one that is only revealed when she lets go. It is only then that moving on becomes possible.

The ever present water imagery follows Jia Jia to Tibet — which, she also notes, has the world’s highest freshwater lake — and An Yu juxtaposes the bustling solitude of Beijing with the spiritual serenity of Tibet. From being shunned by her in-laws and called a bad omen by Leo’s parents, Jia Jia finds a friend in Ren Qi and is even welcomed by her tour guide’s family. It is with them that more about the “world of water” is revealed and more mysteries follow.

An Yu employs multiple genres — from a noir thriller with a touch of romance to a mystery with elements of fantasy. The transitions are seamless, folding into one another, making the story — with its simple writing — quite evocative and gripping. Jia Jia reaches the end of her search, with a better understanding of her past and the “world of water”. An Yu’s last line has a cyclical conclusion, one that is intriguing and a touch more positive: “Tomorrow, she decided, she would be painting the sea.”

This artice first appeared on June 21, 2021 The Edge Malaysia.

Purchase 'Braised Pork' for RM49.90 at Kinokuniya here.