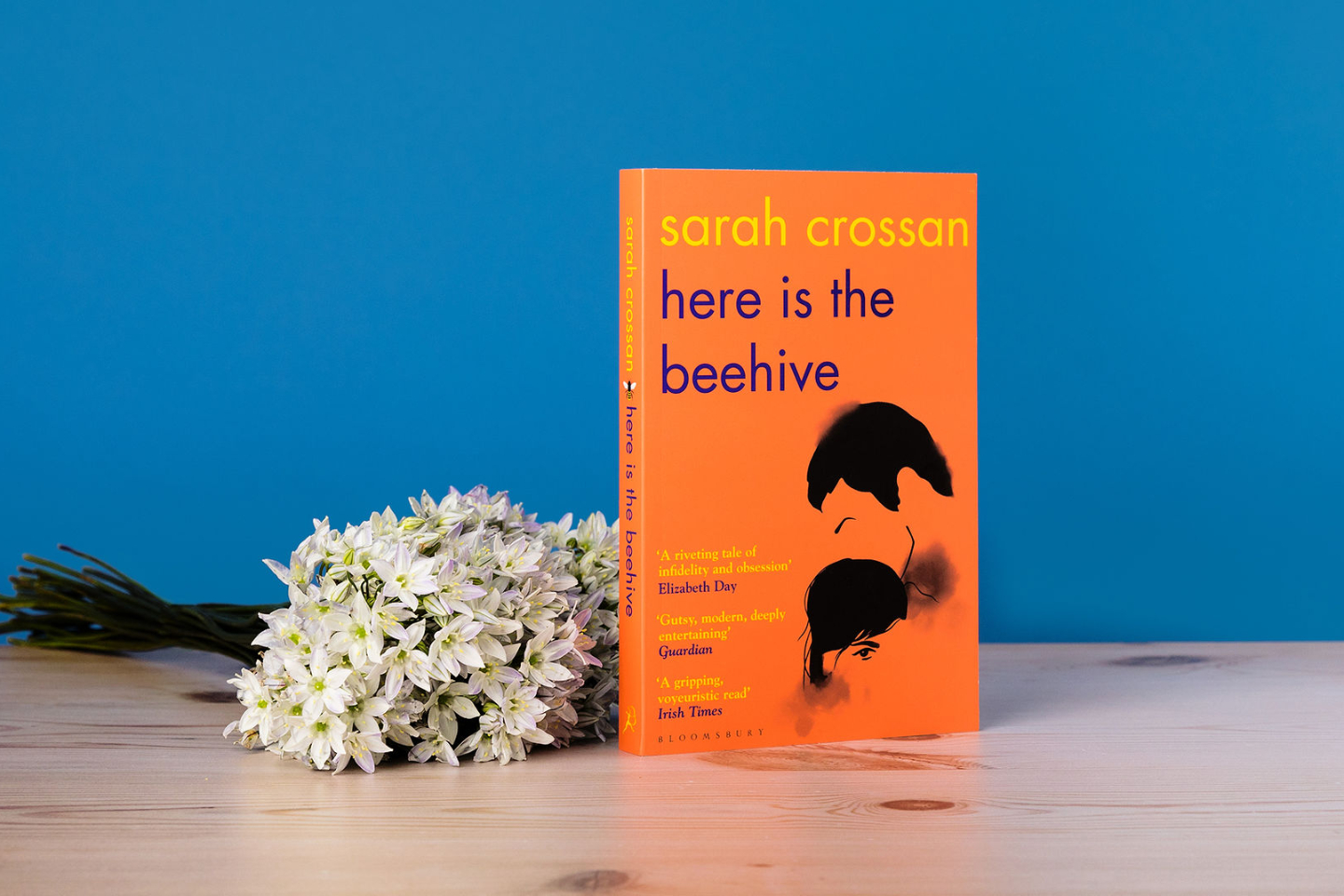

Here is the Beehive, Irish children’s laureate Sarah Crossan’s first adult novel, is written in verse that is terse, lyrical and revealing (Photo: Bloomsbury Publishing UK)

Grief, shrouded by guilt, stymies Ana Kelly’s mourning when her lover dies abruptly. Connor Mooney had walked into her legal firm three years earlier to discuss his will and trusts for his sons, and into her stale married life with homebody teacher Paul.

The mother of two is initially bewildered when she catches herself trying to arrange something with Connor outside the office. “I don’t know what’s happening to me. It wasn’t the kind of thing I did; wasn’t the sort of woman I was.” The next time they meet, Ana decides she likes Connor too, after her best friend Tanya notices his interest in her. She surrenders herself wholly to him because everything he brings is new and exciting.

As happens inevitably when one party wants more than the other can give, the affair loses steam when declarations of love and tiresome promises come to nought. The last time they speak, Ana calls Connor a prick and says she cannot trust him or carry on any more before hanging up, to shut out the “hollow clamour of our arguments”.

News of his death, relayed over the phone by his oblivious wife Rebecca, throws Ana into a tailspin. Feeling bereft and cheated of what she wanted from their liaison — easy domesticity, where you lie side by side, feet touching — she schemes to get something of his, as though to prove what they had together was real. The plan is single-minded and almost manic.

sarah_crossan_by_ger_holland.jpg

Here is the Beehive, Irish children’s laureate Sarah Crossan’s first adult novel, is written in verse that is terse, lyrical and revealing. It throbs with the intensity of stolen getaways in hotel rooms that are like boxes of lies, furtive phone calls, not at the weekend and not after five, and hurried meetings in places the pair knows they will not end with sex.

Crossan’s fresh, original approach to an old plot drives the story with an urgency perhaps reflecting the fact that life is finite: Flawed Ana confesses to lies and deceit with unflinching honesty as she comes undone. It is a riveting narrative that is raw and real.

The succinct prose allows her space and time to flit between present and past, to dart around trysts, telling the reader intimate details about Connor and talking to him as though he is there — sometimes amusingly, sometimes accusingly.

Acceptance that he is now nothing but ash after days of hopeful disbelief — could this be some trick or a case of mistaken identity? — layers their ongoing “dialogue” with a melancholy that evokes sympathy for Ana, the partner left behind who has to mourn her loss in secret.

From the start, Connor tells her he cannot leave because of Rebecca’s pain. Besides, she will never let him go. His best friend, Mark, the only witness to his relationship with Ana, puts it another way: “Rebecca is not the sort of woman you leave.”

There are things Connor does that remind Ana she is always the mistress, no matter how long or happy their romps. He hides her, makes her invisible — the other woman’s deal. In return, she is consumed by desire, by the smell of a man with whom, when she laughs, it rings around the room? “No one made me laugh like that or cared to try.”

Ana chooses to believe the picture Connor curates of Rebecca — his wife is tardy and given to drink; he cannot stand the smell of her. She paints Paul in a bad light and comes to believe it. She wishes Rebecca dead and wants Connor to want the same. When he is killed instead, it is as if the universe listens.

Paul is crushed that she is always somewhere else and Ana admits, “I had caused it. We had.” He tells his spouse, through a maze of silence, “Someone has to go.” Connor suggests they sort out their marriages, then find one another afterwards. His mother counsels that marriage is hard work and he attempts to try again and again and again with Rebecca. Ana, prepared to walk out following her heart, demands he chooses between them. Death takes that decision out of his hands.

Crossan leaves Connor’s three boys and Ana’s daughter and son out of the domestic picture until halfway into the book, which makes it fall short somewhat. They are there, a part of meals and chores, though not in the pressing, messy way kids are. That makes it easier for Ana to “fix” appointments with clients or spend nights away then slip back to her humdrum household, but harder for readers to feel her remorse and shame for hurting the family.

When her daughter, Ruth, snaps her monogrammed coloured pencils in half, then into quarters, Ana steps away, the sound of the snapping of her child too loud to ignore. In physical agony one night, she wonders whether her son Jon will remember her if she were to die then. Sadly, we do not empathise with her fear or pain.

Clients seeking legal advice and action add dabs of colour to Ana’s sorry story. Mr Young loves his son but will disinherit him if he becomes a she, chemically and physically. Mr Bray inherited a house from his uncle, who haunts him nightly, giving advice on where Mr Bray should watch the fireworks; when Mr Bray should plant a hyacinth. “He wants a restraining order,” she tells Connor.

People close to her slide in and out of her life because infidelity has room only for two. Tanya, who softens Paul in a way she never could, is the shark to Ana’s mermaid — his comparison. She abandons their gals’ travel plans at the drop of a stranger’s pants, but is there when it matters.

Older sister, Nora, who got what she wanted as a child by making cruelty a joke, tells Ana she does not look like dad and could be illegitimate. That would explain why Nora is pretty and her sibling, plain.

Their mother, rid of her philandering husband after years of pretence, is dating a much younger American Navy SEAL who is Dutch and lives in Islamabad. And why not? She is lonely and her daughters do not seem to care, whereas he wants to know how and where she is every day.

At a New Year’s lunch, Nora pretends not to see her husband flirt with a blonde by the bar. If Phil cheated more blatantly, mum remarks, she could leave, no blame.

Ana accuses her of allowing their father to cheat, hundreds of times. Mum tells her she is always so sad, not realising nobody wants that for her. “And you shouldn’t want it for yourself.” Is this her mother’s way of saying, be your own woman and choose joy?

Purchase a copy of 'Here is the Beehive' at Kinokuniya for RM59.90 here.

This article first appeared on Dec 20, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.