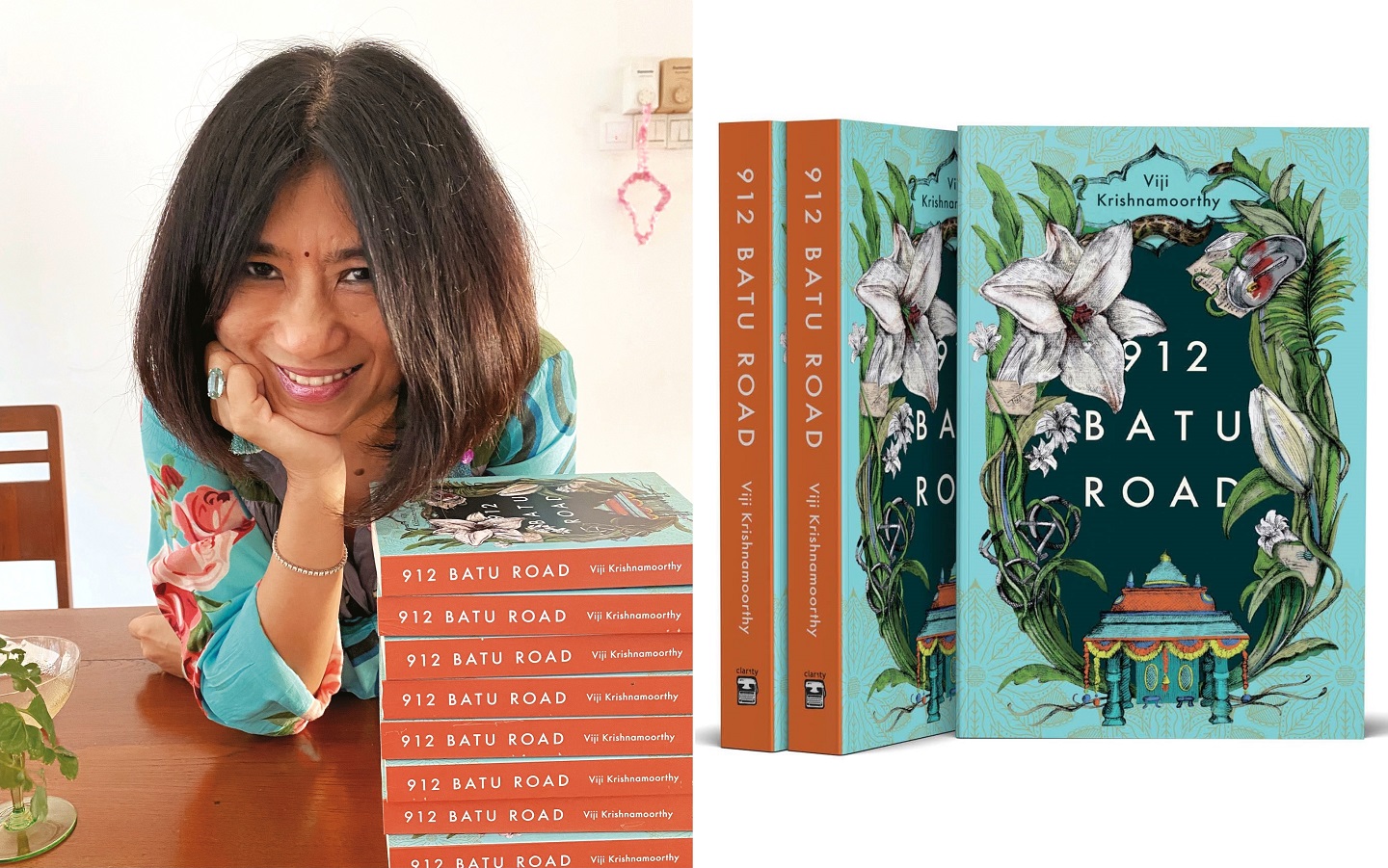

'912 Batu Road' started off as a single chapter more than 20 years ago (Photo: Clarity Publishing)

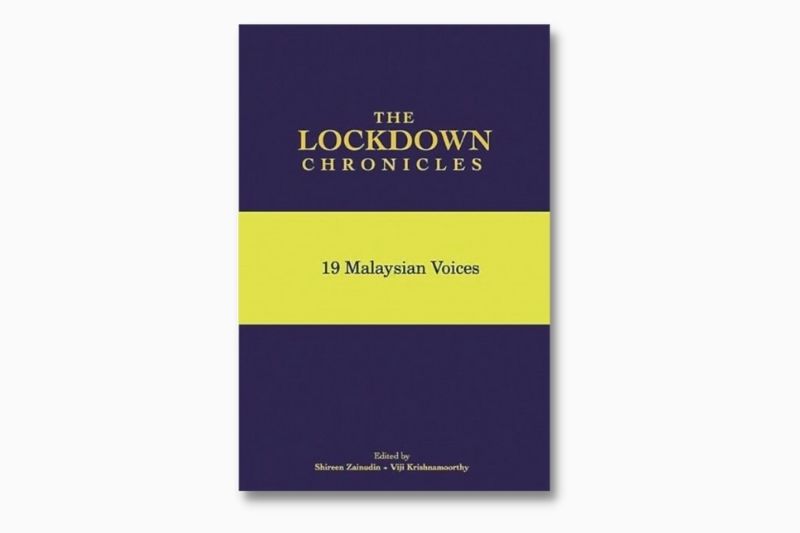

Viji Krishnamoorthy gets a high from spending quality time with family, breaking bread with close friends, having an evening sundowner — a glass of ice-cold Sauvignon Blanc — with her husband, inhaling the scent of a good bookshop and cracking the spine of a new book.

She will get to do a lot of cracking with her first work of fiction, 912 Batu Road, available in bookstores from September. It is her second book, after The Lockdown Chronicles: 19 Malaysian Voices, which she co-edited last year. Here, Viji talks about the seed of the novel, the people, smells and tastes that colour its pages, and writing from a deep place within herself.

Options: A book titled after an address is not common. Is 912 Batu Road a real or fictional place?

Viji: It is not very common but two titles come to mind: 44 Scotland Street by Alexander McCall Smith and 84, Charing Cross Road by Helene Hanff. There is a little backstory as to how my book came to be called 912 Batu Road.

When I bought my first car, I requested either 219 or 321 for the number plate. The only number available was 912. When I drove the car to my aunt’s house to have it blessed, she stopped in her tracks and asked me what I knew about 912. I didn’t, except for the fact that it was the reverse of 219! That was when she told me 912 Batu Road was the house my father was born in. I didn’t realise its significance until then.

Since many of the scenes from the past centre around a Tamil Brahmin household, 912 Batu Road made sense, as it sort of anchored the book. That number has followed me ever since, in small and significant ways. That’s why I wanted this title.

viji_krishnamoorthy.jpg

What was the seed of your story?

It started off as a single chapter, a birthday gift to my husband Ranjit, more than 20 years ago. With some tweaks along the way, it became part of chapter one — Getting to the Mandapam — which is primarily about the bristly and sticky friction between Geeta and her mother Parvathi. It really was a joke and a lame excuse of a gift. All through the years when we dated, Ranjit and I wrote letters to each other. This was a nod and a throwback to that simple but meaningful mode of communication, really.

We live in such an instant world today, we have forgotten the longing and agony of waiting for an aerogramme. This was around 2000 and we started doing some research — Ranjit helped me with that — but I didn’t seriously put pen to paper for the next seven years. My first draft was completed in 2010 and even though a few friends read it and encouraged me to polish it up, I had such self-doubt. It wasn’t until 2018 that I plucked up the courage to do something with the manuscript.

Sybil Kathigasu, Gurchan Singh and Lim Bo Seng figure in the novel. Why this interest in war heroes?

The past in this story is historical fiction. It starts in 1940, when war was already on the horizon. After Japan invaded Malaya, Sybil Kathigasu, Gurchan Singh and Lim Bo Seng were patriots instrumental in the war effort against the Japanese. Gurchan was one of the key figures behind the Malayan Resistance Movement, The Singa Organisation, that was responsible for the morale-boosting Singa posters. Lim, a Singaporean who returned to Malaya to join the Resistance, was one of the leaders of Force 136. Nurse Sybil, together with her husband Dr Abdon Clement Kathigasu, treated wounded members of the Resistance, despite the grave and life-threatening risk of being uncovered by the Japanese.

These heroes are woven into the pages of the book. It would not be possible to write a story set between 1941 and 1945 without acknowledging their contribution and pay tribute to their bravery and love for the country.

Historical fiction allows writers to take liberties with facts. Did you?

Yes, of course I did. (Rabindranath) Tagore’s visit to Kuala Lumpur and the Victoria Institution on Aug 4, 1927, is historically correct. He did read his poems from The Crescent Moon, but I am not sure if The Merchant was one of those he read. Sybil’s and Gurchan’s acts of bravery and patriotism are accurate but are threaded through fictional plots. For example, the bicycle race at the Penang Turf Club is fact, but Gurchan’s escapades with Tochi are fictional.

Does your own background — Tamil father and Hokkien-Chinese mother — inform the novel?

Yes, there are certainly brushstrokes from my own memory bank that have coloured aspects of the story. Although I am of mixed parentage, my upbringing was entirely Indian. I speak Tamil fluently and learnt Barathanatyam at a young age and was sent along with my sister to boarding school in then-Madras. We grew up in an extended, very close-knit and noisy family of uncles, aunts and cousins. Sunday lunches were very much a part of my young and adult life and that of my two children’s too, as were the siestas that followed!

Writing chapter five was so tactile. I could almost put my hand through the page and touch the slightly oily re-purposed Nutella bottle of ghee, smell my favourite tart lime rasam, open the lids on all the different pickles my aunt used to make and, truly, the conversations we had as a family around that dining table made for weighty memories. The priority was food, family and, always, the politics of the day.

As I spent several years in the UK as an economics student, some of the places Geeta visits are favourites of mine, as are her love for Jo Malone’s Orange Blossom perfume, Sauvignon Blanc, the colour orange, Malaysian artist J Anurendra’s work and Indian authors. When writing the book, I retreated to a place deep within me and drew from smells and tastes that were not just familiar and experiential but embedded and often buried under the debris of living.

A three-generation framework is popular in fiction. Why did you use that?

I wrote from three different generations because ultimately, this is a story of migration. We read of stories of Indian migration to the West, but I haven’t read any that tells the story of a migrant Indian to Malaya, and the Tamil Brahmin community in Malaysia is very small. And it would have been a similar journey my grandfather made in the early 20th century.

Does history bring something to a book that real-time narratives lack?

This story has both — history and real-time narratives in the present. I am no historian, but historical events lend a colourful and often dramatic canvas to set a story against. And history informs us of where we come from; it affords us hindsight and insight and is the thread that stitches us to the future. In 912 Batu Road, the letters Rangaswamy writes to his father in Tanjore are the link that connects Geeta to her forefathers/mothers.

the_lockdown_chronicles.jpg

Plot, setting, dialogue, fact check, rewriting — which was the hardest for you?

I think it would be all of them at different times and in varying degrees. Because this book has taken so long, my language and style have evolved with time, age and life experiences. I would say rewriting or wanting to rewrite parts was most pressing, but working on the structure, plotting it all out, making sure the ages stacked up, the years were right, that places existed in the years I wrote them in and even the language Rangaswamy used when he wrote to his father, very different then, was authentic.

How did Clarity Publishing come into the picture?

Rosalind Chua, the principal of Clarity Publishing, is a close friend of a close friend. We were introduced to each other. After she read the first draft, she saw promise where I saw doubt.

Ever get writer’s block? When that happens, what do you do?

I walk away, do a jigsaw, light a candle, play some mahjong, have a glass of wine or two if it’s in the evening! Or I talk to my sister and close friends, who always bring cheer.

Any early book influences or favourite writers, and what are you reading now?

Always, books by Enid Blyton, from Noddy to Malory Towers; Rupert Bear by Mary Tourtel; of course, the inimitable Alice in Wonderland; A House for Mr Biswas; and Pride and Prejudice. My favourite authors are John Steinbeck, Jane Austen, Rohinton Mistry, Elif Shafak, Erma Bombeck, Chinua Achebe, R K Narayan, Jhumpa Lahiri, Anita Desai and Elena Ferrante.

I am currently reading Disoriental by Négar Djavadi and keep dipping into and out of The Best of A. A. Gill. The man is a genius. I enjoy reading historical fiction and clever stories like The Time Traveller’s Wife, Q & A, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, The Kite Runner, Educated and the four Neapolitan Novels.

20210406_peo_viji_shireen_6807_izw.jpg

What did you learn from working on The Lockdown Chronicles that helped with this book?

The Lockdown Chronicles was a project my co-editor and dear friend Shireen Zainudin suggested to me soon after we met after the lifting of the first Movement Control Order. We gathered 19 voices as a nod to Covid-19 and each wrote a piece of fiction to reflect the unparalleled global phenomenon we were all navigating.

912 Batu Road was written and completed long before The Lockdown Chronicles but, for sure, there were lessons to be learnt: primarily, to realise not everyone will enjoy, like or appreciate all the stories but to accept them in the spirit in which they were offered. Shireen and I are now working on a coffee table book. I also contribute to Mynd.Asia, a delightful digital platform.

Do you worry about how readers will take to your debut novel?

Absolutely! The hardest part for me was to pluck up the courage to put my work out there in the public space. I am still not comfortable with it, which was part of the reason it has taken so long for it to see the light of day. I wrote this quote by Rick Rubin on the front page of my diary: “You are one-hundred percent successful as soon as you send your project off into the world … regardless of how it is received.” I am not there yet, but I try and remind myself when I feel unmoored.

Purchase a copy of Viji Krishnamoorthy's '912 Batu Road' at RM39 from Clarity Publishing here.

This article first appeared on Aug 16, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.