Dina explores themes of love, grief, loss and longing, and the magic in our lives (All photos: Dina Zaman)

What Dina Zaman missed most during her Chevening scholarship year in the UK was the sea. “English seas didn’t smell the same as those in Terengganu,” the writer and researcher says. “I love England, I really do, but I didn’t think I could do a Wuthering Heights too long.

Going up and down Lancaster and London was fun, but her mind would wander back to Kuala Terengganu (KT), where she had fabulous times when young. Lancaster University, though brilliant, was near farms and she remembered thinking “all the animals were fat, while our cows, sheep and goats back home were anorexic”.

Thoughts of home found their way into stories that started as her creative writing master’s project in 1998/99. It gave birth to three works: I Am Muslim (Silverfish Books, 2007); King of the Sea (Silverfish, 2012) and The Road to Elvis, a novel she has turned into a film script.

After I Am Muslim — a compilation of selected articles she wrote for a column in Malaysiakini about what Islam means to Muslims in the country — Dina’s publisher Raman Krishnan suggested a book of short stories. As she had all of them in her hard drive, it seemed the natural thing to do. That led to King of the Sea (KOS) in 2012.

“To be honest, I don’t wake up thinking of [doing] a book. My writing, fiction and non-fiction, has always been organic. I scribble here and there, in diaries, post-it notes, and pool them in one pad or word document. Then I take it from there.”

Likewise, the 2024 edition of KOS released this month by Clarity Publishing was unplanned and sudden.

Dina had signed up with Devina Sivagurunathan, who co-founded literary agency Sivagurunathan & Chua with Rosalind Chua, to publish another book, Malayland. When the latter asked for a copy of KOS, she sent one and did not think much about it.

After reading the first three pages, Chua decided she could not let KOS get out of print, and suggested that Dina include new stories to show how her writing has evolved. As the latter was doing more work in Terengganu then, she set to it last November.

Thus, The Treasure Hunt, The Last Indian Man Left Standing in Kuala Terengganu, and The Birthday Cake (first published in Everything About Us: Readings from Readings 3, 2016) were added to the collection.

In Birthday Cake, Rohani meets her lost love from decades ago at a deserted playground near midnight. “Why now,” Razif asks. She has a question for him too: “Why didn’t you come for me that night?”

Looking back, Dina admits to being “very tentative” when working on the original edition, and thinks she went deeper with the characters in the new pieces. A lot of her fiction, the writing at least, is inspired by American authors. They are spare in their sentences, but allow the reader to indulge in their imagination.

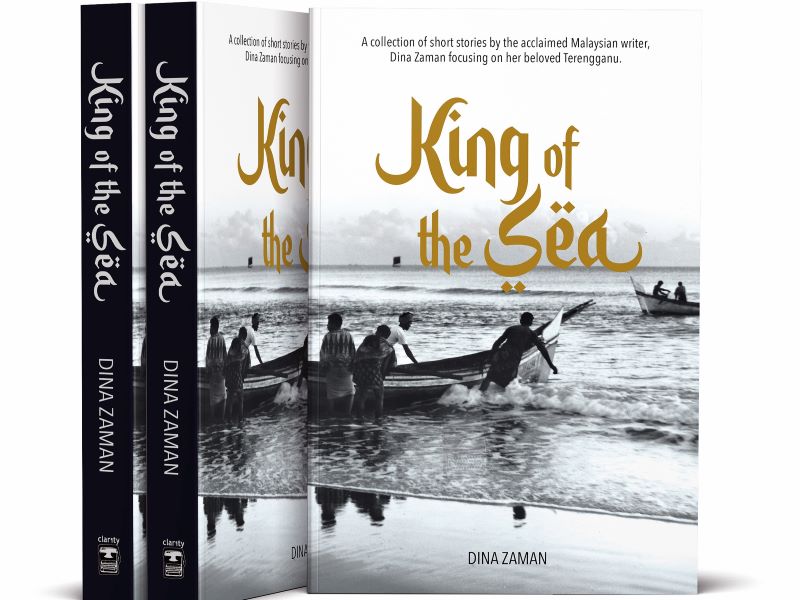

Harry Sinclair Lewis and Richard Ford are among those she adores. The female writers tend to be French, but she looks up to them for the same reason, from Marguerite Duras, Françoise Sagan and Nobel laureate Annie Ernaux, to the astute Italian novelist Elena Ferrante. KOS is about “love, loss and longing in a land where mountains meet the sea and magic fills the air”. On its cover is a picture by Almarhum Sultan Ismail Nasiruddin Shah of Terengganu, the fourth Yang di-Pertuan Agong and an avid photographer, courtesy of his grandson Raja Ihsan Shah, Dina’s cousin.

Some of the tales were inspired by those her mother told her — such as, Masbabu, set in Kampung Bunga Keladi, where the men around Ipeng, who wants to fly after his wife dons feathers and dies in a fire, begin to change after too-colourful, too-loud Masbabu arrives with her husband.

king-of-the-sea.jpg

There are strange accounts of bunian, spirits, angels, a missing child who returns as a chicken, and a boy grieving for his father who meets a ghost that tells him he is king of the sea.

“Of course, I believe in magic. All these stories were part of my childhood,” says Dina. “You cannot be Asian without having a healthy regard for it.

“Now this is where I get academic: I feel when the ordinary Malay(sian) moves to urban areas, they lose a huge part of themselves. Traditional spiritual healing plays such an important role in the Malay psyche. One ends up in the Klang Valley, and all this is replaced by modernity, science, gadgets.”

Local dialect crops up in conversations in KOS. It is not deliberate, more a natural course because “when I think or write in Malay, it is in the Terengganu dialect”, shares Dina, who spent years abroad. Her diplomat father had long overseas assignments and the family was in Japan and Russia in the 70s and early 80s. But happy days in Terengganu with her maternal grandmother are imprinted in her memory.

“What I can remember of my childhood is that when we were in Kuala Lumpur, I’d attend Convent Bukit Nanas or suddenly I’m in the car on the way to my grandparents’ place. I didn’t spend years under my grandma’s care, but I did spend a lot of time.

“KL has never been home, though it has given me a platform to write and work. I guess home is Terengganu. Maybe I’m romanticising it, but the state makes me happy. Yeah, it’s PAS led-now. I don’t care. I just want to do my thing, and be left alone.

Again, water comes to mind when she talks about home. “I remember the rain a lot. Monsoon season in the East Coast will either make you mad or sanguine. The rains in KL are tepid and hold no stories.”

Such as The Rainstorm, in which a dripping wet girl peeps through a window and sees two pairs of legs sprawled and intertwined on the bed — her mother’s and another that is slim and taut, with a small scar near the ankle. Or The Last Indian Man Left Standing who, every time it pours, imagines a heavy breasted woman crouching over his tiny house, beating the roof with her breasts while crying her heart out.

Terengganu, like Kelantan, has this reputation of being conservative, dead and boring, says Dina, who has written extensively for Malaysian newspapers, reckons the media perpetuated that image of both states.

“Yes, we have problems, but KL also ada. I will say this: Terengganu is very sensual. I have family and friends there, and they do very interesting things. We are more than just a green flag.”

Seeing her artist friends dump the capital city to move to the East coast, Dina hopes she will be “next to abscond, although Indonesia and London are great too”.

She is still a regular contributor to the Jakarta Post, writing about politics and what makes Malaysians tick. “No, it doesn’t get harder with time; it’s more like needing more time.

“I’m one of the founders of IMAN Research and I fundraise for the outfit. I’d rather research, read and write than fundraise these days. But non-profits in Malaysia always no money, so kena cari la duit.”

With stories and books on identity, religion and politics to her name, Dina says fiction allows her to create whatever she wants. “Writing that and film scripts — these I don’t expect to be produced, I just do them for fun — is freeing. It’s like weight training, therapy and yoga — it’s just you, you, you.”

She is also author of Holy Men, Holy Women (SIRD, 2018), a collection of essays resulting from her two-year journey around Malaysia, during which she met with and talked to people about faith, what they believe and how they worship.

Malayland, part memoir and part observation, will be co-released by Faction Press and Ethos Publishing in November. It explores what it means to be Malay and Muslim in a Muslim-dominated country that is still insisting on more Malay-Muslim rights.

Meanwhile, the script for The Road to Elvis, a coming-of-age tale about three Terengganu kids in the 1980s, is sitting in her G-drive. “Do you have money for us to produce it?”

And, always, home calls. Dina’s current passion projects revolve around Terengganu Royal History. She has no idea where this will lead but is hoping for a documentary. “I’m not seeking a Datukship, if you’re thinking that! Whatever I do is driven by curiosity.

“Terengganu’s history, royal or state, is very interesting. We are a state of rabble-rousers. We were also once a renowned regional port. We may be religiously conservative, but we’re also socially capitalistic. We’re neoliberals, really.”

This article first appeared on Aug 19, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.