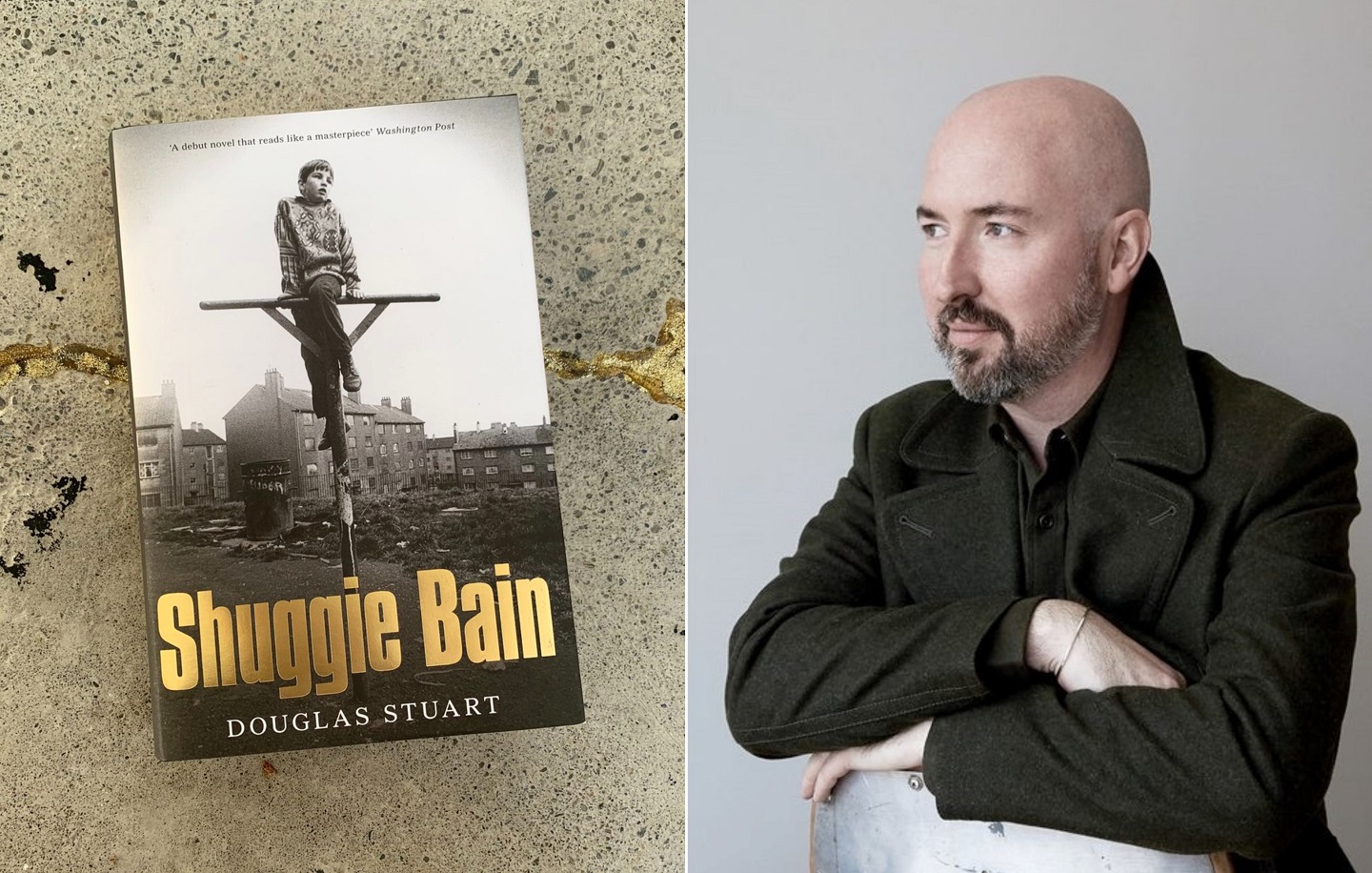

At the end of Shuggie Bain, readers may wonder: Must one lose himself so that others can find themselves? (All photos: The Booker Prizes)

Just hours ago, the Scottish-American was named the Booker prize winner this year for his debut novel Shuggie Bain. “Destined to be a classic” as The Guardian calls it, the story is based on his own life that follows a boy growing up in poverty in 1980s Glasgow. Read our full review below:

Shuggie, named after his father Shug Bain, lives in cramped lodgings in the southside of Glasgow, Scotland. Readers are introduced to him as an independent young man who has worked at a takeaway for over a year, despite having an employer who fails to notice their grimy surroundings.

Douglas Stuart’s rich description of the city in Shuggie Bain takes us on the road travelled by this unfortunate but diligent lad who is loyal to his mother, Agnes Bain — a road he wishes to divert from but cannot. Battered by harsh reality, the Bain family heads towards a dead end.

It is the 1980s and Glasgow, in the throes of deindustrialisation, is filled with unemployed miners and housewives stuck at home with their “weans” — the little ones. Poverty narrows one’s options. With nowhere else to go, Agnes finds escape through alcohol and eventually ends up in the crematorium.

She is married to taxi driver Shug, a typical working-class guy, and they live with her parents Lizzie and Wullie in a high-rise housing estate in Sighthill. Shug assures his wife and their three children that the future will be promising if they move out of the confined quarters. Already an alcoholic, Agnes is excited about starting anew in a different place, hoping to rebrand herself as a wife and mother in the traditional sense.

shuggie-bain_1.jpg

As hard as it is to break the cycle of poverty, so is the reinvention of Agnes. Heavily dependent on Shug, she looks to him to pull her out of the darkness. But her addiction, coupled with his philandering ways, disintegrates a marriage that was never solid in the first place. A master manipulator, Shug exploits Agnes’ trust as he abandons her and the children, leaving her deep in the dark world of drink.

Alcohol ruins the only constant relationship Agnes has with Catherine, Leek and Shuggie. One by one, the children start to give up on her for the burden she has become to them. Eventually, even Shuggie, who has been loyal throughout her manic episodes, tastes sour betrayal.

Objectification is a crucial element in Stuart’s story. Agnes’ graceful and alluring appearance, which she takes pride in, puts her at a disadvantage as she is viewed as another sexual object by ruthless men. Looks can be deceiving, and that is the case with Agnes, who models herself after Elizabeth Taylor: Her beauty veils the fact that her life is a wreck.

It does not help that Glasgow is also known as a masculine city for its industrial activities. Shuggie, far from the conventional male, and Agnes who is glamorous, albeit unsettled, soon find themselves outcasts. And like them, various female characters in the book become victims of male violence.

Shuggie is an isolated lad defined by the family’s struggles and his own confusion about his sexuality. His feminine traits draw him towards dancing, playing with pony dolls and hanging out with girls. As a result, he is subject to homophobia from the community and his own family. But as they cling to each other, Agnes is the only person who lets Shuggie be and shows him the true meaning of unconditional love: “If I were you, I would keep dancing.”

Stuart draws a clear distinction between Shuggie and his other characters, who have thick Glaswegian accents. Agnes teaches him to be polite and speak in a posh dialect, although that gives bullies more reason to taunt him for being “not man enough”. She believes he will always be kind and empathetic despite his unusual interests.

Though everything seems bleak and gloomy for the Bain family, Shuggie remains optimistic that his mother will eventually come out from her dark hole. Despite the many times she fails to deliver on her promises, he has faith in her.

“She was no use at maths homework, and some days you could starve rather than get a hot meal from her, but Shuggie looked at her now and understood this was where she excelled. Every day with the makeup on and her hair done, she climbed out of her grave and held her head high. When she had disgraced herself with drink, she got up the next day, put on her best coat, and faced the world. When her belly was empty and her weans were hungry, she did her hair and let the world think otherwise.”

At the end of Shuggie Bain, readers may wonder: Must one lose himself so that others can find themselves? This beautifully heartbreaking book explores love and pain. Neither pretty nor gruesome, it has a realist approach that walks us through the lives of a mother and child who struggle to find their place in the world.

It also teaches us an important lesson: As much as we want something to happen, some things are beyond our control. When Shuggie learns that, our protagonist moves on with his life.

This article first appeared on Nov 2, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.