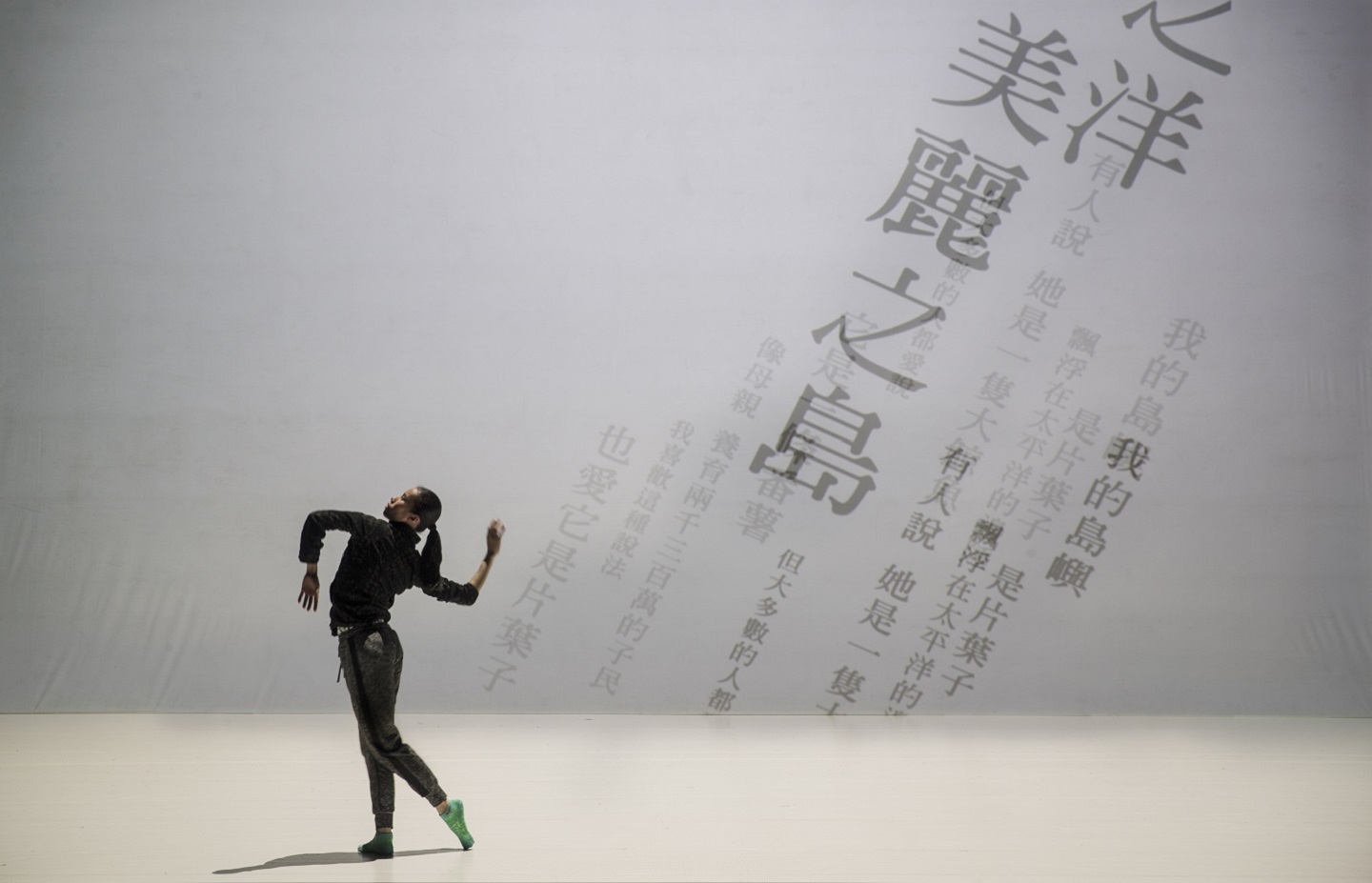

A dancer gracing the stage beside text projections (Photo: Cloud Gate Dance Theatre)

Are words alone enough to describe the beauty of a place? Perhaps not, but it can certainly be a catalyst for imagination. In the case of celebrated choreographer Lin Hwai-Min, words were the starting point of his most recent work, Formosa, an award-winning production by Taiwan’s foremost contemporary dance company, Cloud Gate Dance Theatre.

The title itself draws inspiration from the exclamation of Portuguese sailors as they first laid eyes on the East Asian island in the 16th century. “Beautiful!” they declared of its lush vegetation and mountainous landscapes.

Echoing that is an unabashed tribute of love to a nation that, through his distinctive brand of East-meets-West dance creations over four decades, Lin has helped put on the international map. Beyond being a trailblazer in the Asian contemporary dance scene, the founder and artistic director has given visual life to the often tumultuous Taiwanese narrative over the years through the stage, his pioneering works of Western dance technique imbued with Oriental roots carrying a spirit of unyielding identity — both of its land and its people.

As he is set to retire this year, Formosa is likely to be Lin’s swansong with Cloud Gate, and so what better way to end an illustrious career than with a sort of “valedictorian meditation” of his beloved country, as The Guardian aptly put it in its review of Formosa’s staging at London’s Sadler’s Wells Theatre last year.

The show, which went on to win the Stef Stefanou Award for Outstanding Company at The Critics’ Circle’s National Dance Awards 2018 in the UK, will make its way to Istana Budaya this weekend for its only performance in Southeast Asia.

Viewers can expect a world-class dance performance as well as a contemplative experience, stirred perhaps by the unmissable digitally projected Chinese characters, or Hanzi, presented throughout the performance. In an interview with Options, the man behind the video art, Chou Tung-Yen, shares its significance in the show.

“When Lin began working on Formosa in 2015 and 2016, he invited me to join the project. He said he wanted a video projection based on the Hanzi. I mentioned that it’s quite a common thing to do in popular culture these days, but he said, ‘It’s okay, what we want to do is something different’,” explains Chou.

“It wasn’t just about turning on our computer programme and typing some words in stylistically. Master Lin first found a Chinese writing expert to conduct a class for us. We learnt about the history of its development, like how the printed language came about, how it transformed and evolved … From the get-go, he also gave us a wealth of literary works related to Taiwan, from poems to prose,” Chou shares.

The established video artist, documentary filmmaker and theatre director then led a team of artists in designing a video projection for the hour-long performance, a process that he says was like plumbing Lin’s mind and trying to see his vision.

Another visual cue given was American abstract expressionism works from the 1960s and 1970s, while Chou himself also looked into works by Cai Guo-Qiang, the Chinese visual artist. Nature also provided inspiration, both in wording and visuals.

“There are sections where we used simple texts such as names of mountains in Taiwan, its rivers and seas as well as indigenous and common local birds. Visually, we looked at things like shale, formed through volcanic activity and lava flow … how it is created layer by layer. We then created our graphics to that effect,” illustrates Chou.

After studying the literal meaning of the text materials, the video artist’s challenge was then to deliver a work that is cohesive with Lin’s narrative, yet have a new graphical meaning that transcends the boundary of language. “Our most important emphasis wasn’t on the words’ literal meaning, but their abstract one that would, in the end, still bring forth the idea for the scene. An example is the 1999 Jiji Earthquake. Lin wanted us to use text to recreate that idea of catastrophe,” he says.

He admits that working on Formosa was quite an uncommon process. Chou says Lin worked individually with the musicians, dancers and costume department, which makes it all the more fascinating how it came together. He also choreographed the dances after the video projection took shape.

“We only saw the big picture at the final rehearsals,” he adds. The result is a work that has the trademark Cloud Gate poetry and elegance, juxtaposed against a stark and bold backdrop of visual texts and guttural vocals for a soundtrack. Amidst it all, the dancers move lightly and fluidly at junctures and distorted and manically in others, narrating the story of a nation coming to be, its growing pains and its reckoning with what it is.

The ebb and flow of the text, co-existing on stage, speaking a different language but sharing the same message, underscores that shifting of landscape. “Ultimately, it is about the people, individuals, their relationships, the ones who are in love, the ones who have encountered catastrophe, how they respond to that … How do we bring it out?” Chou asks rhetorically. I guess we will have to find out for ourselves how a story of beauty can be conveyed through dance and words.

'Formosa', Panggung Sari, Istana Budaya, KL. 012-502 6883. Mar 16, 8.30pm; Mar 17, 3pm. RM98-468. Buy tickets here. This article first appeared on Mar 4, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.