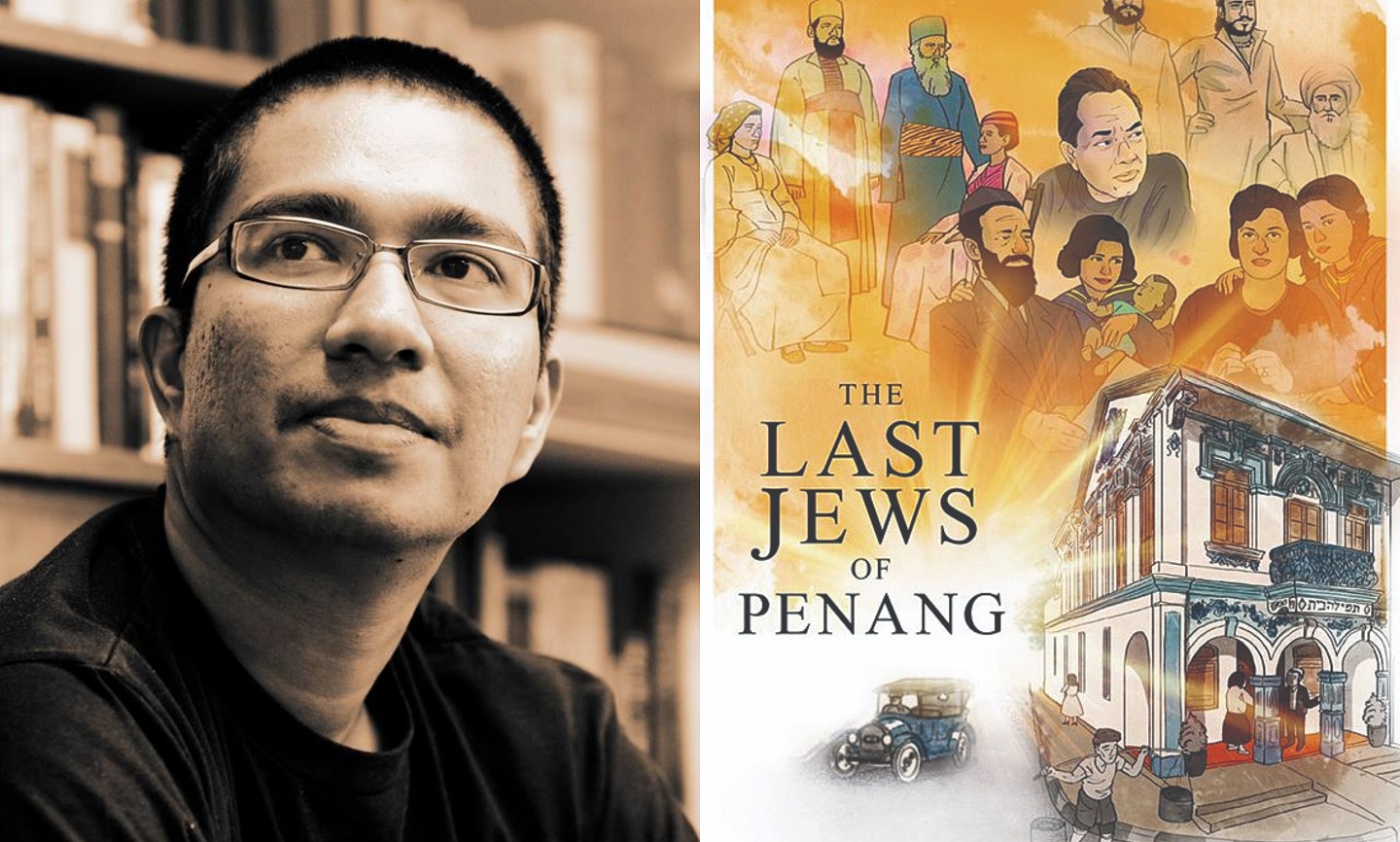

Amir is also open to a Malay translation of The Last Jews of Penang (Photo: Matahari Books)

Publishing The Last Jews of Penang was a symbolic gesture by Amir Muhammad to pay tribute to the Jewish writers and filmmakers he was drawn to when he graduated from chidren’s books and stories. Off hand, he names William Goldman, Billy Wilder, Woody Allen and Marc Leyner as among those whose work he enjoyed.

Not that they have anything in common with the Jews featured in his illustrated book released last November. Not to say, too, that they are orthodox. “Most of them are not. It’s a certain sensibility that comes with [being Jewish]. I owe a lot to them for all kinds of things and thought it’s my time to pay back.”

At the same time, no one else was doing such books in the country, so he thought he might as well, Amir adds.

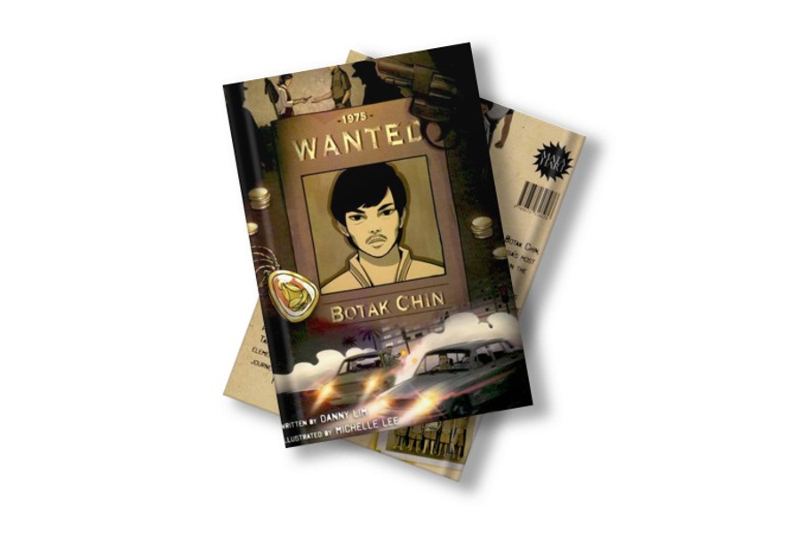

The Last Jews of Penang is the third illustrated title by Matahari Books, crowdfunded and following the same format as its predecessors. In 2020 and 2021 respectively, the imprint of Buku Fixi specialising in non-fiction released The Malay Tale of the Pig King and Wanted: Botak Chin.

The first is Heidi Shamsuddin’s retelling of the Hikayat Raja Babi, originally written in 1775 by Semarang merchant Usup Abdul Kadir, with illustrations by Evi Shelvia. The second is freelance author Danny Lim’s 40-page biography of Wong Swee Chin, aka Botak Chin, based on news report of Malaysia’s most notorious criminal in the 1970s. Michelle Lee did the pictures.

A fourth book, on the Batek, indigenous hunter-gatherers living in the Kenyir area north of Pahang, will be out later this year. The writer is Wong Pui May, whose proposal was among the 27 Matahari received in response to ideas for illustrated titles Amir hopes to bring out yearly. Wong’s work will be written in English, Bahasa Malaysia and the language of the Batek, who number about 1,500 today, and focus on sustainability, centred on a question a child might ask: Why can’t we take more?

botak_chin.jpg

“Her proposal is quite complete — she knows what she wants, the approach and all that. Some of the other ideas just wanted to get a message across, which is what adults do in children’s books — they want to teach, whereas children don’t want that. Even the Batek book has to be fun enough to draw people in and make them want to find out more,” says Amir, a writer and filmmaker who publishes to “delight” readers.

Going back to The Last Jews of Penang, he thinks many will wonder about the cemetery alongside Jalan Yahudi (now Jalan Zainal Abidin) and the synagogue at nearby Jalan Nagor; what attracted the people to the island; who was the first person to be buried there (a Mrs Shoshan Levi in 1835); how the Penang Jewish community continued to observe traditions like the Sabbath; what were its numbers during its heyday (172); how the community shrank as a result of the war; the last person to be buried at the cemetery in 2011 (David Mordecai, general manager of Eastern & Oriental Hotel), long after the synagogue closed in 1976, and its present use as a restaurant.

Amir had wanted to do something about this intriguing community since 2011, after reading “The Last Jew to Leave Penang”, published by Free Malaysia Today. “I liked that Stephanie Sta Maria put faces and a family history into this rather abstract idea that there used to be Jews in Penang, something we all knew because there used to be a Jalan Yahudi. Hers was the first article that interviewed one of them and it was a very concrete, warm kind of factual story.”

But he could not decide what to do with the story. He thought of a documentary — “Who to interview; everybody is dead?” — or mockumentary, in which someone is flipping through the channels of a Jewish version of AlHijrah.

A tentative first step came some years back when he did a talk at Khazanah Nasional, and imagined what if there had been a series of movies made by the Malayan Jewish community, with titles like Suami Aku Rabbi and Izinkan Aku Menjadi Kosher Pada Ku. “I roped in [graphic designer] Arif Rafhan and we made posters on that. It was quite well received; some people were credulous enough to think it was real. It died down after that.”

In 2021, hostilities broke out between Israel and Palestinian resistance groups and there was a flurry of activity on Twitter. “Zayn [Gregory] was one of those countering a tweet that said, ‘This is why we should have killed all Jews’. That’s why I thought it was a good time to start an illustrated book.”

matahari_books.jpg

It was timely too because Amir was casting around for ideas for a third such book. He then contacted Kuching-based Zayn (they have never met) to write the text and Arif (who illustrated Buku Fixi’s Hikayat Nabi Yusuf and Hikayat Raja Babi). Interstate travel was restricted and they had to work virtually. But with everyone looking for things to do during the pandemic, there were no distractions once the project began.

Limited verified information and visual reference on the Jewish people who lived on what was then Jalan Yahudi (“Yehudi” is Hebrew for from the kingdom of Judah) in Penang, was a challenge. Old pictures from the Penang Heritage Trust were a big help, but some were so blur they could not tell what was going on. The illustrations were strictly based on what they had because “our aim was to record, not embellish. It was better we got it right than put in things that were not there”.

Amir is open to a Malay translation of The Last Jews of Penang, if there is interest. Unlike the Jewish writers and filmmakers who have had an influence on him, this book is “just a little thing to show we have done something about that community. At the very least, it provides a visual vocabulary for something that maybe we would not have a vocabulary for before this”.

What’s next? “It would be nice if we could have an illustrated book on a subject other publishers wouldn’t do. Like the Kadazan ritual of talking to the dead a few days after their passing, to ask if there is any unfinished business. It’s meant to be a kind of closure.”

This article first appeared on Feb 28, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.