Fahd Razy and Daryl Kho

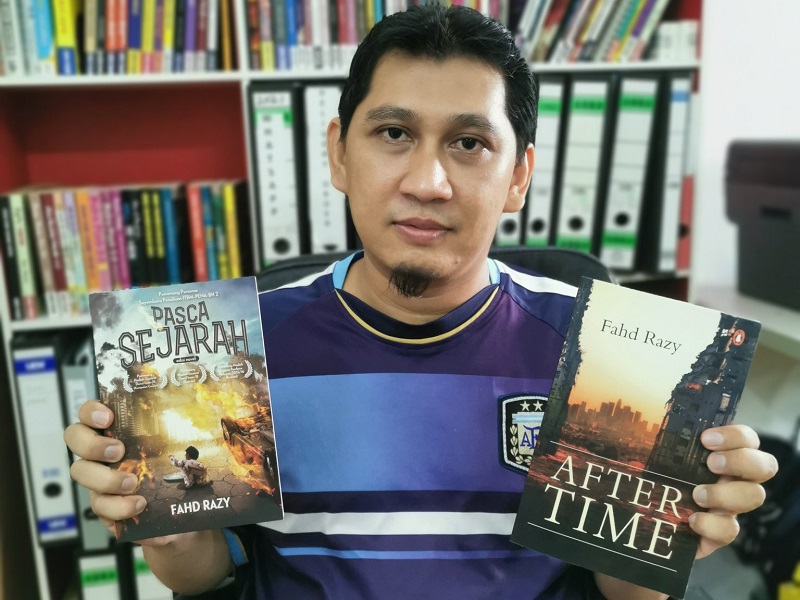

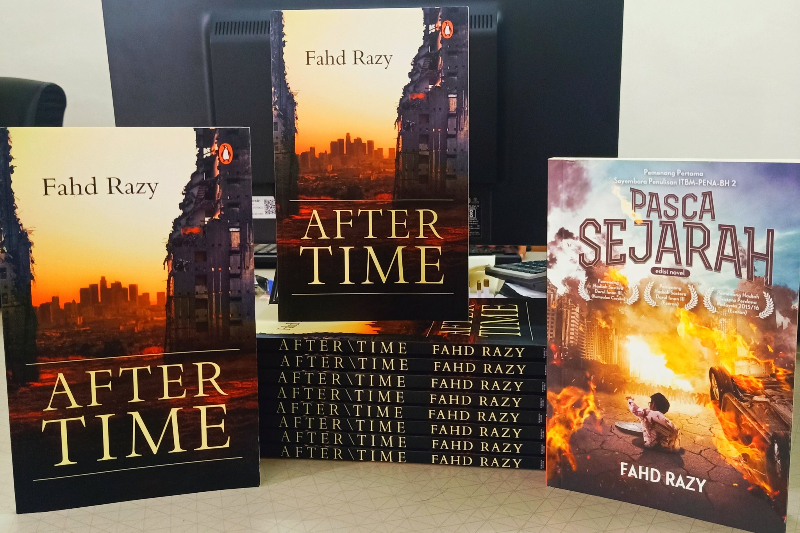

Dr Fahd Razy, a medical officer in Kuala Terengganu, started producing creative writing in 2000, from short stories and poetry to play scripts, essays and anecdotal books on his field of work. His debut novel, Pascasejarah, was a finalist for the Hadiah Sastera Perdana Malaysia 2017. Translated into English as Aftertime and published by Penguin Random House SEA, it will be launched at the GLTF. Fahd now runs Penerbitan Kata-Pilar.

How did your journey into creative writing begin?

In 1998, after watching Deep Impact and Armageddon, I suddenly had this strange urge to write science fiction. The idea of bringing the world to the brink of extinction really fascinates me. I just picked up a pen — I was in boarding school then — and started to draft a story. The plot and characters had been haunting me, which made the writing process fast and smooth. Without thinking or hoping too much, I mailed the story to Dewan Siswa magazine. A few months later, they published it in 1999. I had no idea people could be writers. I was not an avid reader either. Because of that story, I was invited to a week-long writing workshop (Minggu Penulis Remaja) and also won my first literary prize (Hadiah Sastera Siswa-Bank Rakyat 2000).

It has been 22 years since. How do you keep at it?

After my first published work, everything seemed to go wrong. I wrote a lot but all my works were rejected by editors. I tried poetry but failed terribly. I have kept copies of these and always laugh at myself when rereading them. I thought my good start was just a fluke. Then I took a step back and realised that becoming a writer is not just about writing. More importantly, it’s about reading — lots of reading. That’s how I grew fond of reading, up till today. At some point, I even memorised pages of the dictionary just to improve my vocabulary.

After three years, my second work, a poem, finally got published in a local newspaper. For me, writing is the end-product of reading. If I stopped reading, my work would get dull, or perhaps I’d gradually stop writing. I find beautiful phrases, sentences and metaphors really captivating. I can keep reading the same poem, even the same line, over and over again, amazed by how the writer arranged the words. Maybe that’s why I love to write poetry more than prose.

I guess the major obstacle during that early miserable period was myself — too eager and overly confident of my capability. During my time at the Royal College of Surgeons, Ireland, I had difficulty accessing reading materials. Every time I returned to Dublin after the holidays, 80% of my luggage was taken up by books, whereas other students had sambal, ikan bilis and serunding. I was able to set up a mini-library there, which piqued my classmates’ interest in literary works.

dr_fahd_razy_aftertime_pasca_sejarah.jpg

Do you have to juggle between medicine and writing?

I have been writing since secondary school, which means medicine has had to slide in and adapt to my reading and writing. Writing is my passion; medicine is my responsibility. Once you’re dedicated to something, there’s always a way. Besides, writing is my way of relieving stress.

Is it unusual for medical doctors to write fiction?

Perhaps during the early 2000s, when I started. Nowadays, there are many medical doctors who excel in creative writing; most are my friends. But people still believe medicine and creative writing are opposite poles; they think science and art are like oil and water. It’s not true. That’s why, when invited to give talks to students, I emphasise how anybody can be a creative writer — you don’t have to choose one and drop the other. Science and the arts are applied and manifested in our lives.

Are your books for a specific audience?

After writing lots of literary works, I realised I hadn’t really used much of my skills and experience to contribute to my field. At that time, most medical-related books were didactic and factual, making health subjects seem exclusive and less appealing. People love stories and humour, and we doctors have lots of that. Before we can educate people, we must first make ourselves approachable. I started to write anecdotes with a more relaxed and humorous tone to entertain and also teach the public about medical issues and facts. We doctors are human, with lots of weaknesses and limitations. I want people to see our field from our point of view, not the hype and grandiosity portrayed on TV or in movies.

What will you be doing at the GTLF?

My publishing company, Kata-Pilar Books, is also involved in GTLF. We are launching Bayang Sudah Pandai Mengejek by Zul Azlin Razali and Seluruh Alam Dalam Sebutir Debu by Saharil Hasrin Sanin, both short fiction, on Nov 25. On Nov 26, Penguin Random House SEA will release Aftertime, my first book in English. The next day, I will take part in a forum discussion on Surrealism, Futurism and the Absurd with Bora Chung, Daryl Kho and Badrul Hisham Ismail (which makes me very nervous).

fahd_razy.jpg

You have more than 50 books and even written and directed plays. Does writing come naturally to you?

I always create opportunities for myself. If I just write and send my work to the editors and wait until it gets published (or thrashed), it will take a very long time. That’s why I build my own platforms. During my college years [2004 to 2009], I created an online literary community called Grup Karyawan Luar Negara to promote literature among Malaysian students abroad. It had up to 500 members from over 20 countries, with more than 10 subdivisions. We had online discussions, meetings, workshops, writing competitions and publications. Many of the group members have established themselves as writers, publishers and book advocates.

I wouldn’t say I’m a natural writer. Maybe because of my science background, my thought processes are more technical and concrete. I always feel writing is like finishing a jigsaw puzzle — there are many wrongs before I get it right. I need to really search for ideas, plots, sentences and words. My problem is, I’m never satisfied with what I’m writing. I have hundreds of raw and unfinished drafts on my phone and laptop, waiting to be finished.

What do you hope readers will get from your writing?

When writing about medical subjects, whether facts or anecdotes, I hope to educate the public. There are a lot of myths, misconceptions and ignorance related to health and medicine, which sometimes result in heartbreaking consequences. I love to experiment when writing prose, explore different techniques, construct unexpected plots and create a new world while conveying my thoughts on a subject. Most of the time, ideas and settings come first. For me, good plots equal good stories.

Will you eventually concentrate on just a few genres?

Currently, I’m more into poetry and medical anecdotes. Since having my own publishing company, I’ve found a new kind of satisfaction in recruiting new and young writers, besides seeing my own works published. Seeing theirs get published, receiving positive feedback and even winning literary awards makes me feel very excited.

How did Penguin Random House secure Aftertime?

Aftertime is a translation of my debut book, Pascasejarah, first published in 2015. It won first prize in the Sayembara Penulisan ITBM-PENA-BH. ITBM had planned to bring out a translated version, but that didn’t materialise. Then my friend Dr Adibah Abdullah — she’s a doctor and a very good creative writer too — translated it into English.

Initially, I thought of self-publishing, but since it’s my first English novel, I wanted to get it right. I started researching publishing companies and came across Penguin Random House. I still can’t believe my manuscript has been accepted by such a big and well-known publisher. I’m now working on an English version of short stories about my experience in the medical field — all the interesting, heartbreaking, inspiring and peculiar cases I’ve encountered in the past 13 years.

Aftertime is about humans destroying themselves because of greed and cunning. Why this story?

The idea for it started while I was in medical school. I really loved history and mythology at that time and read a lot about them. I found a pattern in human behaviour, particularly with regard to the growth of civilisation. One terrifying fact that has never been refuted is that all civilisations, without exception, will collapse. The big question is: When will it be our time?

Did you have encouragement from anyone in particular when starting out?

I must not forget my secondary school teachers, Cikgu Rabita and Dr Shamsudin Othman, who first noticed my interest in literature and encouraged me to pursue it. Then, there are fellow writer friends who create an encouraging environment for me to write. Writing is solitary work, but becoming a writer is a collective process. I don’t think I’ll last by working alone and isolating myself. My family has been very supportive too. When I have something in my head and need to write it down, they immediately understand and give me the space to do so. I always share my ideas with my wife and she constantly gives constructive feedback. Each time I finish a new piece of work, she becomes my first editor and proofreader.

What about authors who influenced your writing style or content? Do you have any recurring themes?

I used to read Dewan Sastera magazine and still do. It exposed me to different styles of writing by different authors. For short stories and novels, Faisal Tehrani, S M Zakir and Anwar Ridhwan are my favourite authors — they enlighten me on how to write good prose. For poetry, I read a lot of works by Dr Shamsudin Othman (who introduced me to lots of writers and good books), A Samad Said, Zaen Kasturi, Rahimidin Zahari. My writing has evolved. Initially, I focused more on spiritual and religious themes, perhaps for catharsis. As I travelled during my student years, I wrote about foreign history, culture, civilisation and politics. I have met lots of patients and their relatives, each with their own unique attitudes and circumstances, who give lots of inspiration and stories. I also began to explore new genres, such as medical anecdotes and non-fiction.

You have won many awards over the years. Do they spur you to write more and better?

Awards motivate me to do more. I feel acknowledged. At the same time, they set bars that I must surpass. Attention and publicity from awards create awareness and discussion. Besides producing a good piece of work, making sure it reaches as many readers as possible is also important if one wants to be a successful writer.

Any particular interests besides writing and reading?

I really love martial arts. I was a founding member and instructor of a gelanggang silat in Dublin. I also love watching movies; they are really helpful in getting new ideas and techniques for writing. Currently, I’m quite into collecting LEGO mini figures.

---

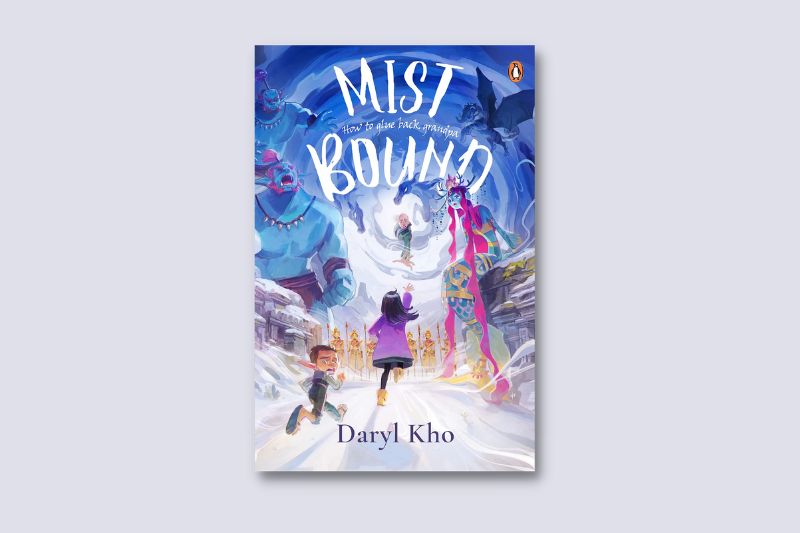

daryl_alexis.jpg

Daryl Kho’s Mist-Bound: How to Glue Back Your Grandpa (Penguin Random House SEA, 2021) is a fantasy novel inspired by his father’s affliction with, and eventual passing from, dementia. It won the Hedwig Anuar Children’s Book Award by the Singapore Book Council, given to the country’s most outstanding children’s middle-grade book of the past two years. It then won the 2022 Singapore Book Award for Best Young Persons Title (ages 7-18 years), presented by the Singapore Book Publishers Association. Now based in Singapore and working as a media rights licensing professional in the regional broadcast industry, Kho sells other people’s stories for a living. During his student days in Malaysia, Canada and the US, he composed poetry, songs, plays, musicals and even kung-fu skits.

Would you say events such as the GTLF are a good vehicle for reaching new audiences?

Yes they are and even more so indirectly. They’re great for industry networking, with other authors, publishers, distributors and press: connections that could potentially lead to doors to new markets and audiences. More so, conferences and festivals are amazing learning experiences for me, especially when I was starting out as a clueless wannabe author. Particularly so the Asian Festival of Children’s Content, because they had sessions like ‘How to get published’ and ‘Great Book Openings’, which served as Beginner 101 courses on the publishing industry and the craft of writing. In addition, the AFCC provides an amazing platform for aspiring authors to pitch in person to publishers, in a ‘speed-dating’ type set-up. That’s where I pitched to Penguin SEA, which eventually led to my book deal. This will be my first time at the GTLF and I’m really looking forward to it!

You started writing seriously again after your father’s dementia diagnosis. Did it help you come to terms with that, and his death?

This book came to mean many things for me. Originally, it started out as a paper bottle of memories, created to contain mementos of my parents, to be passed down to my daughter Alexis, and even her own kids and grandkids.

Unintentionally, it ended up also becoming for me a repository for sadness and an outlet for grief and guilt. Sadness about his condition, for his lost memories and lost personality that then turned into grief when he passed. Guilt for failing to be a better son, for failing to be there much, for not just being unable to prevent but also inadvertently causing his condition. You see, he had his first stroke hours after we’d had an extremely unhealthy fat-laden father-son catch-up meal at my favourite kopitiam.

The making of this book also became a refuge from a series of career setbacks that I was going through then. It gave me much-needed reassurance that I still had it within myself to create, and still had value to offer.

mist-bound_daryl_kho_2.jpg

Between the time you started working on Mist-Bound and completing it, your daughter grew up. What did the book do for her and the family that amazed you most?

Yes, Alexis literally grew up with this book. She saw it come together piece by painful piece, through reading way too many drafts for me, witnessing papa tearing his hair out at the keyboard on weeknights and cursing at the computer screen on weekends. She also experienced the results at the other end of the road, years later. Joining me for story readings and author talks, getting interviewed by the press herself and, perhaps best of all, getting to see her own illustrated alter ego sitting on bookstore shelves. Being a teenager now, Alexis would probably deny it, but I suspect she finds it rather neat to be the star of her own book, and that its readers from various places know her by name. She is currently in the literary programme of an arts-based secondary school in Singapore. Again, she would be the last person on earth to admit it, but I’d like to think it went some ways in inspiring her to be a writer herself. Like Alexis in the book, she’s becoming her own storyteller.

Which part of Mist-Bound was the hardest to write? Did its fantastical characters come easily to you?

The hardest part to write were the opening two chapters. Those went through the most rewrites. Because they had to do so much: capture my father as he was before his memory loss; illustrate the relationship between Alexis (the star of the book) and her grandfather as I’d dreamed for it to be had dementia not happened; describe the ‘real world’ the story opens in; contain the inciting incident that took away his memories and through all that, somehow still try to be as entertaining as possible for easily-bored and distracted young readers.

Coming up with the characters and creatures was fun and thus not too difficult. Hitting on the main story idea was even easier. It was perhaps a day after my daughter turned five. I was packing up my childhood bedroom as I was moving my parents to an apartment where dad — not having full mobility as the result of his strokes — wouldn’t have to deal with staircases anymore. I happened across a box of my old college plays. Rereading them re-lit a forgotten flame. That was when I knew I needed to write again. Because Alexis’ birthday was still fresh in my mind, who to write for and what to write came a minute after.

My dad’s stroke, semi-paralysis and memory loss came just three months before she was born, and through that resulting tough period, her birth was the only thing the whole family had to look forward to. As it drew closer, even my dad’s condition improved significantly. Her Chinese name was chosen to reflect that: Rui Qing, which means the first flower bud of spring. It was as though she was his cure, and the end to our winter. So, voila, it dawned on me to write a story of how she would go on a quest to gather the cure to restore her Grandpa’s memories, and one of the key ingredients would be nectar from the First Flower of Spring.

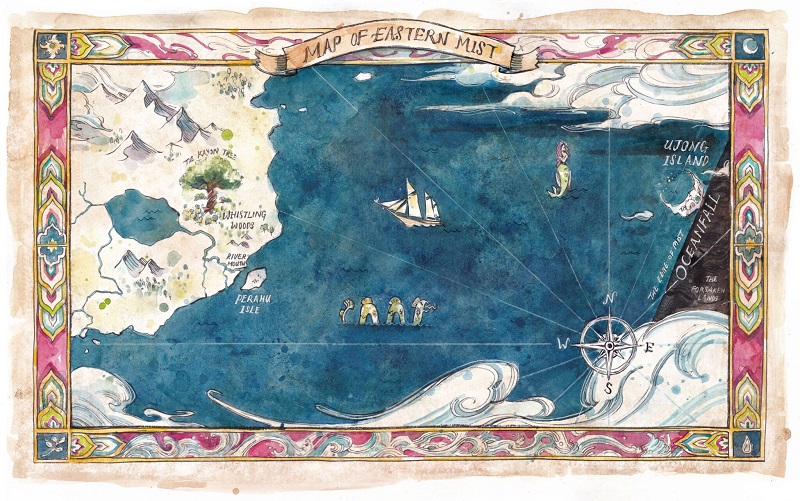

daryl_kho_mist_map.jpg

The artwork for the book is beautiful. Have you worked with Silly Jellie before?

Silly Jellie is an amazing illustrator from Miri, Sarawak, introduced to me by my cousin Serah (a very talented artist herself). It’s our first collaboration and working with her to paint out on paper what I had dreamed in my head was definitely one of the best parts of this book’s journey.

What do you get most from writing?

Rather than joy, the process more often brings me angst and frustration! I’d also say writing was something I turned to whenever I was sad, lonely or depressed. I suppose tears often make good ink. I realised discovering something that helps make you less sad is just as important as finding something that makes you happy. Perhaps even more so. It offers you a way to take something dark or painful and turn it on its head into something of beauty. Like taking a person’s illness and death and turning it instead into a celebration of his life and legacy.

Are you planning to continue with creative writing? Any particular themes or types of books?

In June, I had a short story about the metaverse published by HarperCollins Kids in its anthology for sci-fi and mystery stories called Flipped! It’s a spiff-up of a piece I’d first published way back when I was a high school student. As for writing new material, yes I would like to, but the day job is not allowing me to think too much about that yet. Furthermore, I suspect Mist-Bound will continue to keep me busy outside the office. Post-GTLF, there are a couple of author events slated, including a fundraiser for dementia. At this time of writing, a publishing deal is baking in the oven to translate Mist-Bound for a major book market. I recently signed with a Korea-Los Angeles-based producer who is working on bringing the book from page to screen. (Caution: These things typically take years, if at all, to happen.) So, fingers and toes crossed, Mist-Bound’s story is only just beginning!

Dementia is a growing concern today. Are you involved with groups helping patients and carers? How best can books help?

Sort of like a prosocial enterprise but in book form, I wanted Mist-Bound to entertain but also do some good at the same time. Specifically, it has four main aims, which are to increase appreciation of our grandparents; the importance of family; stories, folktales and myths, especially those from our region and from within the minds of our elders; and to grow awareness of dementia. All these are held together by this central quote that served as the book’s North Star: “When an old person dies, a library burns to the ground.” (Amadou Hampâté Bâ)

When an old person dies, a treasure trove of knowledge, experience and stories is lost forever. When a person has dementia, it’s as though the shelves are in flames and burning through the books while they’re still standing and breathing. Dementia is an increasingly prevalent issue facing families and society, yet it’s often difficult to talk to young children about this disease in an insightful and thoughtful way.

Through its fairy-tale premise, this book helps serve at least as a starting point for early awareness among young readers, and a jump-off platform for conversations to be had about the topic with them, by parents or teachers. Hopefully in a more fun and engaging way, compared to hitting them over the head with dry facts, figures and jargon through a medical textbook.

To drive the dementia awareness objective, Mist-Bound has been supported by non-profit organisations such as Dementia Singapore (part of Alzheimer’s Disease International, or ADI) and TOUCH Community Services, a social services charity. I’ve also worked alongside the Alzheimer’s Disease Foundation of Malaysia (ADFM), which is part of the ADI Network. I’ve done fundraising campaigns, Intro to Dementia radio talks and dementia-related interviews for various video and print publications, groups like ProjectWeForgot (a support community for dementia caregivers), as well as continued to speak about it to students in schools.

A caregiver sharing session event I did last year for the ADFM had special meaning because my dad used to attend daycare there and it was invaluable in keeping him mentally and physically occupied while simultaneously giving my mum much needed time off as a caregiver.

Is fantasy close to your heart? Would you say it’s a quick and most effective way to reach young readers today?

The books that I read as a child gave me the palette from which I paint my world to this very day. There were definitely many influential and inspiring ‘realist’ books. But I think for me, the folklore and fantasy-based stories expanded my range of hues in more ways and directions. They opened my mind to the idea that I could dream up entire worlds that didn’t have to be exactly like the one I live in.

I’m not qualified to speak on what way is most effective. I can only speak from my own experience, as a former young reader and still-overgrown child. Fantasy books are probably why I’m still a Toys“R”Us Kid who never grew up, and why I remain a hopeless, impractical dreamer. But like Grandpa tells Alexis in Mist-Bound: “What are dreams, but memories just waiting to be made? Like ink, waiting to be spilt onto paper and woven into words. Memories make us who we are; dreams make us who we’ll become. So always remember … to dream BIG!”

For more on the George Town Literary Festival, see here. Check out darylkho.com for details on Mist-Bound and its author, and @fahdrazy for information on the doctor-writer.

This article first appeared on Nov 21, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.