A 1950s photo studio recreated for the exhibition (All photos: Ilham Gallery)

In my 96-year-old grandmother’s room, there are a few large photobooks, mainly filled with snapshots of her in the later decades of her life, including those of her travels around the world when she was well into her seventies. But it is the haphazard pile of black-and-white photographs tucked within these books that fascinated me the most while I was growing up.

There are memories of occasional afternoons spent with her going through them, from the dignified profile photo of her as a young woman to prints of my father, uncles and aunt lined up in a row, from their childhood to young adulthood. They were always dressed formally, their expressions mirroring my grandfather’s sombre but striking presence.

During a visit to Ilham Gallery’s current exhibition, Bayangnya itu Timbul Tenggelam: Photographic Cultures in Malaysia, I was reminded of these images, mirrored by familiar scenes of hundreds of portraits and other artefacts.

2_sharifah_aini.jpg

“This project has been a few years in the making, and what you see is but about one-tenth of what we’ve collected,” says K Azril Ismail, one of the curators of the show. The exhibition was initiated by art researcher and historian Simon Soon, though co-curators Hoo Fan Chon and Azril came on board to help shape what has become a showcase of “photographic cultural mapping”.

Bayangnya takes a broad stroke approach to its subject. Typical of Ilham shows, there is a twofold timeline created by Soon as an overarching background — one related to the development of the history of photography and the other, marking key developments of image-making as a tradition. But beyond that, it does not stick to a chronological showcase, diving instead into several loosely categorised segments.

Azril, a photographer and artist in practice, as well as the head of UCSI University’s Institute of Creative Arts and Design, shares during our private tour, “I think we’ve mapped more of how Malaysians have utilised photography as a medium, and also how it affected us. It is more of an anthropological viewpoint.”

And that makes the show an interesting one. The ambitious and massive effort is clear to see, albeit the full potential of these works has yet to be revealed. Still, on a personal level, Bayangnya offers a fulfilling enough sample of an experience that was at once nostalgic, fun and almost intimate.

5_gold_teeth_a.jpg

We start at the photo studio section, complete with a recreated photo studio circa 1950s and 1960s with painstakingly sourced details, right down to a book of transparent watercolour-tinted paper and actual make-up from that era. This is Azril’s self-professed “playground”, where he was responsible for compiling the myriad of studio portraits spanning pre-World War I to the 1970s.

“For me, these photos show the best representation of themselves. Everyone seen here had their own challenges, no doubt. But when they settled down in front of the camera, it was putting their best selves forward,” he notes.

There’s something about still images and how they immortalise more than just a face. “I am present, hence I exist”, the professor echoes, as if voicing their collective subconscious. This seems to be a psyche particularly held by the Chinese community, who were undeniably the biggest operators and customers of photo services. “The Chinese tend to have their lives intersect with the photo studio at many points of life — birth, adulthood, educational or economic success, marriage, in old age with their grandchildren and, finally, death,” observes Azril.

I think back to my grandfather, who emigrated from Hainan island as a young man. The annual trips to the photo studio with his children were a luxury he insisted on, partly to have his family photos kept and mailed to relatives abroad — but also, perhaps, a subtle expression of pride for the life and family he has built here.

collage1_1.jpg

This idea of existence resonates throughout the exhibition, underscoring the cultural importance of photography across all segments of society throughout the 20th century. Apart from the elite, public figures and middle class, we also see a series of images found in an old studio in Penang, featuring “ladies of the night” — women who only came in the evenings to have their portraits taken, when they would not bump into the townsfolk. Some were professional shots for work while others were of second wives in bridal gowns or mistresses with their men and children.

“These may be the only evidence of legitimacy they have of their relationships. If the husbands die, they could at least have a claim to the estate,” Azril points out.

Then, there are the arresting portraits of Ava Leong, first discovered by Hoo, who had found images of a young man and a glamorous-looking woman in a photo studio and realised that they were the same person. So, he tracked down a friend of Ava’s and recovered an extensive collection of snapshots that encapsulates the story of her lifetime and personal evolution.

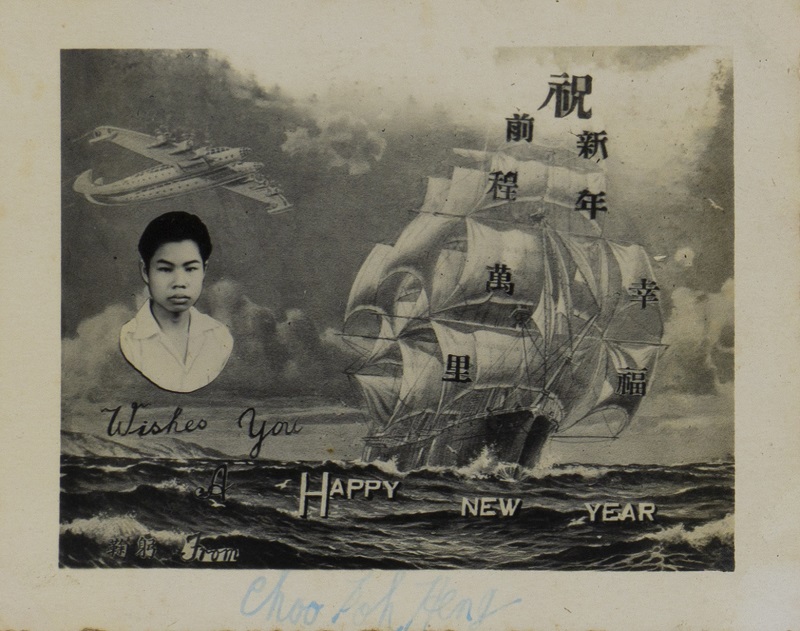

In the bigger picture of things, Bayangnya showcases the development of photography and its purposes, moving from sihir or black magic practices to formal organisational charts, and from personal greeting cards to magazine and album covers and advertisements.

11_moving_house.jpg

Among the quirkier images, we also see the theatrical elements — “magical” shots of people perched on a flying plane, or on top of a building, or dressed in sombrero hats. One may laugh, but I wonder whether future generations will equally judge us for our “bunny ears” and other zany social media filters and poses in the years to come.

Today, with the ability to capture a moment with just a touch, images feel more dispensable. Nonetheless, the magic of photography remains its ability to stir the imagination beyond one’s reality.

Like how Munshi Abdullah recorded his experience of seeing a daguerreotype being created in 1841, “Tapi bayangnya timbul dan tenggelam” (his shadow emerges and disappears), there is the idea of possibilities, memories and emotions evoked. “They are jewellery pieces, heirlooms,” Azril says at one point.

While he was referring to the physical value of silver contained in the photographs, the description feels apt, be it of the people in the portraits or of the treasured tapestry of unspoken narratives that tell us who we collectively are.

'Bayangnya itu Timbul Tenggelam' is available for virtual viewing here. The physical exhibition will run until Dec 31, although it is temporarily closed to the public due to the Conditional Movement Control Order.

This article first appeared on Nov 16, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.