Malachi also founded Men Matters Online Journal (All photos: Malachi Edwin Vethamani)

Malachi Edwin Vethamani came into poetry late, in Form Six, when he had to study T S Eliot for his Higher School Certificate. It immediately had an impact and a strong hold on him. Five decades on, his favourite literary genre still serves him well in his love of language and desire to use it to express himself.

“I’ve always felt poetry is the best and most powerful vehicle to convey the human condition, experience and emotions,” says the writer, editor, critic and academic.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson and W H Auden were early influences, while Eliot continues to fascinate him. Malachi sees poetry getting a lot of attention today, with contemporary writers such as Ocean Vuong, Sudeep Sen, Cyril Wong and Jericho Brown making their presence felt in the literary landscape. This motivates him to write and reach a wider audience.

Kuala Lumpur-born but now living in Seremban, this 67-year-old writes to make sense of what he sees or is happening to people or things around him. But it is not all about self. “I do write with an audience in mind and also to give voice to the many silences I see in things that matter to me.”

Most of his poems centre on life, love, desire and unfulfilled longing, sourced from personal experience and his surroundings. “I am a keen observer and listener. Often what I see, read and hear become triggers for me to write.”

He hopes readers will connect with his work and draw whatever they want from it. “Negotiating relationships — those with family, partners, people, nature and the environment — is something that recurs in my poetry. Contemporary life is filled with complex and complicated [ties] between people, fellow creatures, nature and the environment, and I try to make sense of these things.”

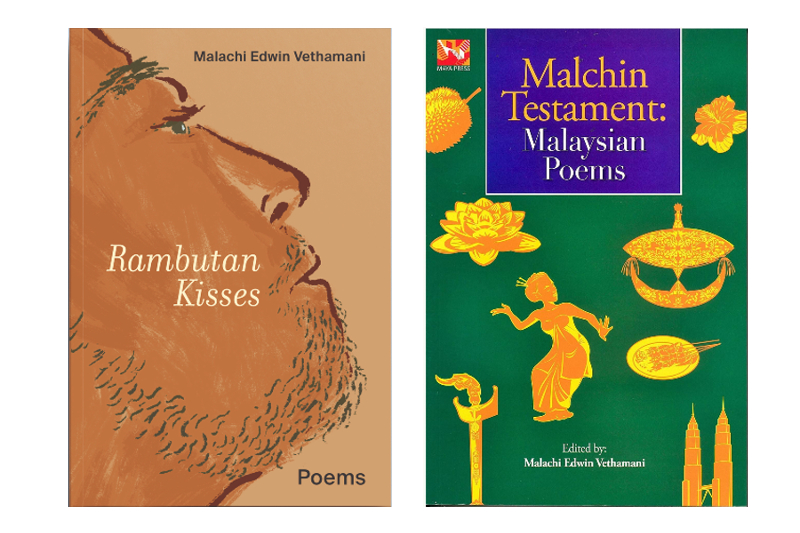

There are several poems on the pandemic in Rambutan Kisses, his third collection, launched at the George Town Literary Festival and the Asia Pacific Writers and Translators Conference in Bangalore, India, last year and in Kuala Lumpur last month. Written over five years, it explores themes from two earlier volumes, Complicated Lives (2016) and Life Happens (2017).

Covid-19 struck before Malachi retired in January 2021 from University of Nottingham Malaysia. It kept him homebound and was a “surreal way” to bring to a close his 42-year teaching career”. He taught at Universiti Putra Malaysia’s Faculty of Educational Studies from 1986 to 2009, was founding dean of Wawasan Open University’s School of Education, Languages and Communication (2009 to 2011), and then joined Taylor’s University as founding dean, School of Education in 2011.

Writing has kept him busy the last few years. In December 2020, he founded Men Matters Online Journal. Published twice yearly, it focuses on topics concerning men, masculinity, gender, culture, politics and sexuality. It also examines what it means to be a man in contemporary society. The sixth issue is due out in June.

He organised two national-level competitions, for poetry and short story writing, in 2021 and 2022 respectively, and has been working on publications resulting from the events.

Malachi’s research interests are currently related to Malaysian literature in English and Malaysian English. He has edited and co-edited scholarly works on Teaching English as a Second Language (TESL).

Moving between academia and creative writing was seamless for him because both are closely linked, he says. “My own writing is informed by what I teach. I was one of those who had to choose profession over passion. Being an academic paid the bills. It helped nurture my passion for writing. The timing was also right as I achieved my goals — I got my full professorship in English literature.”

Asked if he is the rare Malaysian Indian writing poetry in English, Malachi says no, and points out two compatriots. Cecil Rajendra from Penang has been at it since the 1960s and not stopped. And among the younger generation is Ipoh-born Melizarani T Selva, founder of KL’s monthly spoken word poetry open mic, If Walls Could Talk.

malachi_books.jpg

These days, he observes, poets have more opportunities to reach the lay reader when invited to literary festivals, events like Readings@Seksan organised by Sharon Bakar, and open mic events where they get to read their poems.

Spoken word performances are popular with young poets and younger audiences, and he taps these avenues to engage with then. Social media is another platform writers employ to reach new readers, via Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok. He uses all of these, except TikTok.

For those who are keen but step back because they think poetry is inaccessible, Malachi has tips on how to approach it. He suggests that they read poems aloud and pay attention to words and patterns in sentence structures. “I tell them reading poetry is different from reading prose.”

Editing is another opportunity for him to draw attention to other poets, both young and old. “I made a decision quite early in my academic career that I would focus my research, publications and conference presentations on Malaysian literature in English.”

Two books he edited in the last five years speak to that commitment. Malchin Testament: Malaysian Poems has poetry in English from the 1950s to 2015, by more than 50 established and emerging writers. A lot of them were out of print, he says by way of explaining why the anthology, published in 2018. It was one of the results of his research on Malaysian writing for the second edition of his book, A Bibliography of Malaysian Literature in English (2015).

Works featured range from those by early poets such as Wong Phui Nam, Muhammad Haji Salleh, Shirley Geok-lin Lim and Salleh Ben Joned, to pieces by contemporary spoken-word performers like Jamal Raslan and Melizarani.

Local author Uthaya Sankar SB, who writes in Bahasa Malaysia, blogged that Malchin Testament “fills a gap since Edwin Thumboo’s The Second Tongue (1976), a landmark volume on Malaysian and Singaporean poetry in English”.

In 2021 Malachi edited Malaysian Millennial Voices to provide poets aged 35 and below an opportunity to have their writing published and available in bookshops. “It is a great motivation for them to see their work in print.”

Readers also get to find out what they are writing about. The 69 poems form a chorus that speak about everyday concerns, from searching for identity to growing up, and dealing with the loss of parents and grandparents. There is also political satire.

He follows local writing and is heartened to see young writers venturing into new genres. Many of them are gaining attention abroad and being shortlisted for and winning literary prizes.

What disheartens him is that Malaysian writers are not given due recognition on the national literary scene. There needs to be government support for all creative writing in the country, in terms of awards and grants, he says. “But, despite the ambivalence and apathy towards Malaysian writing in English, it continues to grow, thrive even.”

Speaking out is something Malachi seems to do quietly, often unnoticed. Three of his tales from Coitus Interruptus and Other Stories were reworked as monologues and performed as Love Matters by Playpen Performing Arts Trust in Mumbai, India, in 2017 and 2018. A short story, Best Man’s Kiss, was turned into a short play for Inqueerable, organised by Queer Ink in Mumbai, India, on Sept 8, 2019. The event celebrated the first anniversary of the overturning of Article 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which had made consensual homosexual sex illegal, by the Supreme Court of India.

Is giving LGBTQIA+ a voice his way of showing empathy or support? “I want to give voice to not just LGBTQ concerns, but all those who are kept on the margins, kept in the shadows or kept silent. This is evident in the poems in Rambutan Kisses. I believe everyone needs to be respected and valued.

“This is certainly a conscious effort on my part to show empathy. They are not given any tokenism in my writing but treated with honesty and sincerity. I have a strong desire to give voice to things others may not care about.”

Sex crops up in his poetry. Is he pushing boundaries? “Yes! And trying to make the invisible visible and giving voice to that which is often silenced. I hope to make people think about these things and, hopefully, there will be open conversations about the issues I raise.”

Coitus Interruptus, his debut collection, was released in 2018 but Malachi had his first short story published in 1995. He had submitted it to the New Straits Times Short Story competition and it won a consolation prize. Encouraged by the result, he submitted a second story to the paper’s then literary editor, Kee Thuan Chye, and it saw print too.

Over the next few years, Malachi wrote several more. When he had accumulated 10 stories, he showed them to a couple of readers, who had mixed responses. “There were concerns about the subject matter and as I was a government servant, I decided to put the stories aside for a while.”

He only returned to them, and wrote a few more new ones, from 2015. “I found a good editor and the stories took on a new life.”

By then, he was a professor at an international private university, which resolved earlier concerns about what he could write.

Last year was a busy time for Malachi, who names Virginia Woolf, Whitman, Auden, Shelley, Lord Alfred Tennyson, Rumi and Agha Shahid Ali as favourite authors. Besides Rambutan Kisses, he released two other collections, Love and Loss and The Seven O’clock Tree (2022).

Reading is a way “to learn, to enjoy and to enter new worlds”. As for what books are on his table now, Malachi, who tends to read a few writers at a time, cites volumes of poems purchased from recent trips to India, and Preeta Samarasan’s Tale of the Dreamer’s Son, a multigenerational family saga by the France-based Malaysian writer.

Will there be a novel, eventually?

“I’m afraid not. There will be more poetry, I hope. My immediate project is a second collection of stories. I’m reworking a set and getting them edited. Hopefully, they’ll be ready by year end.”

This article first appeared on Mar 13, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.