The National Museum of Western Art, designed by Le Corbusier, was the premier public art gallery in Japan (Photo: National Museum of Western Art)

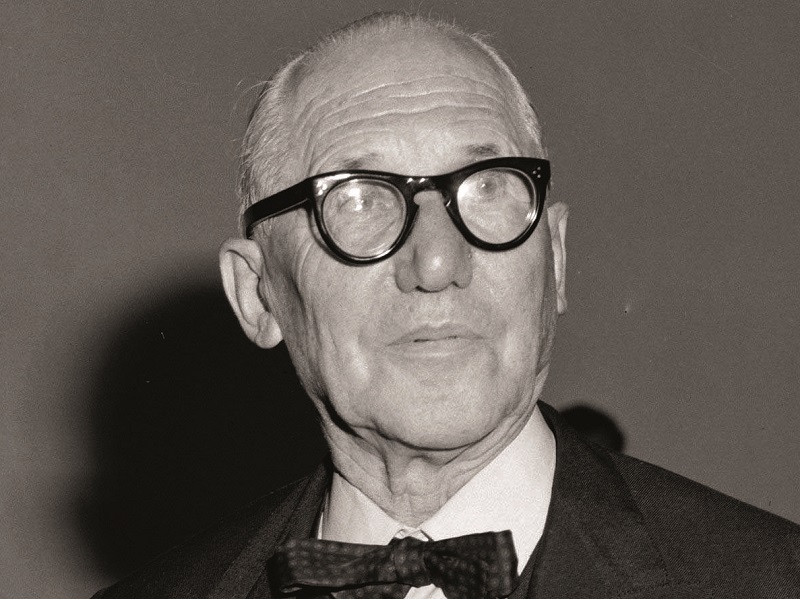

Love him or loathe him, few architects were as iconic — and polarising — as Le Corbusier. Fans use words like “genius” and “visionary” to describe the master of Modernist architecture, while detractors prefer “ahumanistic”, “soulless” and “tyrannical”.

Those familiar with Le Corbusier’s body of work approach it with either complete reverence or hatred — few adopt the middle ground. Even his onetime friend Salvador Dali could not resist a jibe, commenting how Le Corbusier created “the ugliest and most unacceptable buildings in the world”. It does not help that the taint of fascism and anti-Semitism continue to cast a long shadow on his legacy, with the Swiss government removing the Franco-Swiss architect and urban planner’s face and work from its 10 franc bill in 2017, replacing it with the key motif of time instead. Pioneering qualities and peccadilloes aside, no one, however, can dispute the impact Le Corbusier left on the world and how he continues to feature strongly in the vernacular, even over a half-century after his passing. Unesco also saw fit to award 17 of his worksites with World Heritage status in 2016.

From mountains to architectural mogul

Born Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris in La Chaux-de-Fonds, the famous Swiss watchmaking town in the Canton of Neuchâtel where brands like TAG Heuer and Girard-Perregaux are headquartered, the young man was in fact well on his way to assuming a position in the world of timekeeping — as a watch engraver and enameller like his father — before fate, in the form of his teacher, intervened. It was Charles L’Eplattenier from the local Ecole des Arts Decoratifs who felt the precocious lad would thrive as an architect and steered him towards that course, changing his life — and the global architectural landscape — forever.

Not one to shy away from self-expression, Le Corbusier was very vocal indeed about looking to the future, embracing modernity and technological advancements with fervour. He did not hide his disdain for frippery and the Victorian sense of aesthetics, eschewing them in favour of a clean and almost-frugal beauty which, along the way, inspired the next great wave of modernists and minimalists. An amusing side note: Followers might recall Philip Johnson’s rounded glasses which were famously based on Le Corbusier’s signature frame, except that the American architect had designed his own and got them made up at Cartier.

1200px-le_corbusier_1964.jpg

Le Corbusier never wavered from following the guiding light of functional principles, while religiously avoiding the darkness of overabundant detailing and statuary. Even his birth name was not spared. He trimmed it down to just four syllables at the age of 33, adopting a mononym based on his maternal ancestor’s surname of Lecorbésier and thus reinventing himself in the process.

“Le Corbusier is indeed one of the most influential architects … for a variety of right and wrong reasons,” laughs Rene Tan, one half of the well-known Singapore-based architectural practice RT+Q, which he co-founded with T K Quek. “I think it is because Le Corbusier is seen to be ‘over-worshipped’ and that might have become unfashionable within the profession. There have been numerous attempts by students and architects to emulate the master — with varying degrees of success — resulting in pro- and anti-Corbusier ‘camps’.

“Also, because of the wide-ranging aesthetics of his works, which range from the sleek form of the Villa Savoye, and the sublime light at the Convent of La Tourette, to the efficiency of the Unite d’Habitation and grotesque primitivism of the Ronchamp Chapel, he has often been misunderstood. Some love Le Corbusier for his poetry, others hate him for his insensitivity in city planning. He may be praised for his heroics or condemned for his brutality … resulting in sides being drawn.”

Of forms + functions

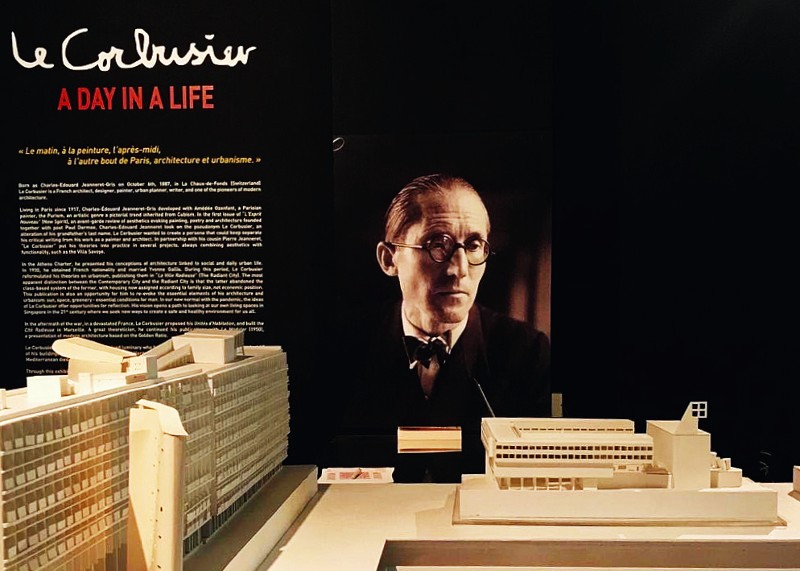

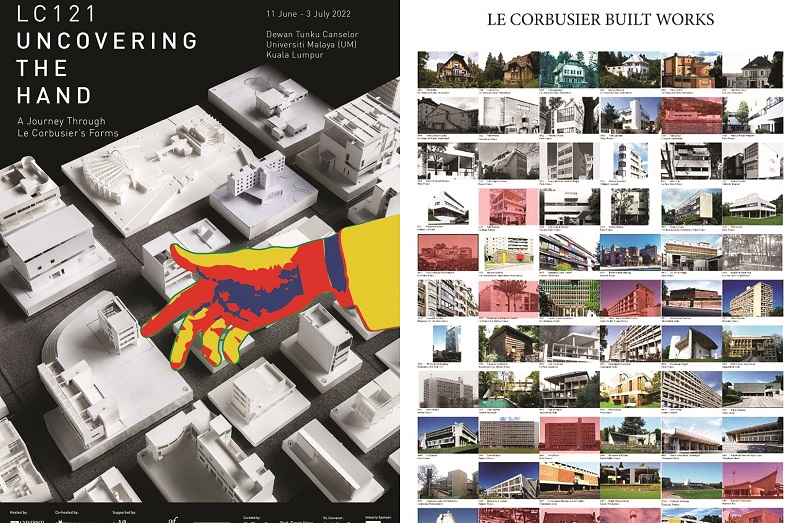

It is this ongoing debate within the architectural intelligentsia that makes the upcoming LC121 Uncovering The Hand: A Journey Through Le Corbusier’s Forms so pertinent. To be held in Kuala Lumpur and Penang, LC121 is the latest incarnation of RT+Q’s ever-growing and evolving collection and exhibition of Le Corbusier models.

“It started last August when Andrew Lau and Fabian Forni of Alliance Francaise and Archifest Singapore found out we had a modest collection of 27 Le Corbusier models,” says Tan. “They mooted the idea of an exhibition so we expanded it to 45 models for the AF/Archifest show in October 2021.”

When ideas are good and exhibitions inspiring, they tend to take on a life of their own. The collection then grew — to 75 models — for the second show at the National University of Singapore, followed by 88 for the third at the Singapore University of Technology and Design and 115 for the fourth — and most recent — show at the National Design Centre. The models displayed are, in fact, the products, observations, discoveries and passion of RT+Q’s young staffers.

“Through the years, it has become tradition for our interns to spend their first week studying and building a scaled model of a Le Corbusier project. Rather than filling up minds with lessons, the aim is to acquaint the aspiring architect with the diverse design legacy of perhaps the most encyclopaedic architect of the 20th century. We amassed quite a few models over the years,” Tan shares.

lc_poster.jpg

Visitors to the Malaysian exhibitions will be able to view a grand total of 121 models for the first time. “We actually have 125, but four are in somewhat bad shape,” he laughs.

Tan’s main collaborator and driving force behind the exhibitions here is none other than Lillian Tay of Veritas Design Group and past president of Pertubuhan Akitek Malaysia (PAM).

“This is a rare and unprecedented oeuvre complète (complete works) of Le Corbusier,” Tay says. “I have seen Rene build up his army of study models over the last 16 years, stacked all over his Singapore office and I wanted the exhibition of models to come here as we have more than 10 architecture schools in the Greater KL area. Students will surely be inspired to see and experience the entire works in tangible, three-dimensional form. The physicality of models gives depth and dimension, making up for two years of online, flat screen learning during the pandemic.”

Tan also shares how he wants visitors to see the larger picture of Le Corbusier, the extensiveness of his ideas and variety of his forms. “He truly was the most versatile of creators and I have often described him as the personification of the architectural encyclopaedia and thought that architecture after Le Corbusier is perhaps just footnotes of him. I myself was influenced by Le Corbusier … but no more or less than any architect of my generation ought to be.”

As the forerunner of the Modern movement, it comes as no surprise that Le Corbusier was taught to everyone who attended architecture school, particularly in the 1980s.

“I grew up in Malaysia then,” shares Tan, “and admired some very nice reinterpretations of the great master in Penang and Kuala Lumpur; most notably, Roof-Roof House by Dr Ken Yeang, the Bank Negara Building by Datuk Lim Chong Keat and Universiti Malaya’s (UM) Dewan Tunku Canselor (DTC) by the late Datuk Kington Loo. Like him or not, Le Corbusier’s influence was pervasive. No one could escape him!”

Saving modern Malaysian architecture

The venue for the KL leg of LC121 Uncovering The Hand was not by happenstance either. Originally designed by Francis Bailey of Booty Edwards Partnership (now BEP Akitek), UM’s DTC comprises many elements of Le Corbusier’s tenets of Modern architecture but adapted to the Malaysian climate.

“The foyer, where the exhibition will be held, is a lofty, naturally lit and ventilated space with a gridded sunshade screen of manually cast bare concrete,” says Tay. “This distinctive brise-soleil, together with the grand beton brut cylindrical stairs of the Dewan is a revered landmark for UM, etched in the memory of every student and teacher. Its unique curving raw concrete staircase will also be featured in a rare architectural tour of DTC on July 3 as part of the exhibition programme in conjunction with PAM’s Kuala Lumpur Architecture Festival 2022. Hence, displaying RT+Q’s 121 models here at DTC is a fitting tribute, both to Le Corbusier and the remarkable legacy of Modern architecture in Malaysia.

lc121_1.jpg

“I must also add how all this would not be possible without Dr Helena Hashim, head of the School of Architecture at UM’s Faculty of Built Environment, who unhesitatingly took up the opportunity to host the exhibition at DTC; PAM president Ar Sarly Adre Sarkum, who promptly helped with funding; and Tengku Zatashah Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah, who is a passionate royal patron of our arts and architecture, and the Alliance Francaise in KL, Penang and Singapore.”

Tay also posits how, in the larger context, Malaysia’s formidable legacy of Modern architecture buildings, particularly the immediate post-Merdeka national buildings of the late 1950s and 1960s, should be better recognised and appreciated as fine examples of Modern architecture in Malaysia, all of which were cleverly adapted to the tropical environment with elements of local cultural motifs.

“Our Modern architecture buildings from this era are practical, climate-responsive buildings. Today, you would rate them as well-performing, sustainably-designed buildings,” says Tay. “Unfortunately, lack of awareness and maintenance has resulted in deterioration and demolition while some faced the worse fate of being insensitively renovated.”

Besides DTC, other notable examples of Modern architecture heritage buildings include but are not limited to Parliament House, Masjid Negara, Stadium Negara, Chinwoo Stadium, Angkasapuri, Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, the Penang General Post Office, Chowrasta Market, the Petaling Jaya Civic Centre, public housing projects like the now-demolished Pekeliling Flats and the soon-to-be-demolished Sungai Pari Flats in Ipoh, and many churches and mosques.

Tay adds, “Visitors to the KL exhibition at DTC will have the unique experience of learning about Le Corbusier’s works in one of the most iconic spaces of Modern architecture in Malaysia still remaining! In that light, RT+Q’s collection of models should perhaps sit in a museum one day … in Singapore, Paris or Penang.”

Friends + collaborators

Long-time friends Tan and Tay met at Princeton University. Tan had earlier completed his BA in Music and Architecture from Yale but earned his Master’s in Architecture from the New Jersey institution.

“Like Lillian, my classmate, great friend and mentor, we perhaps paid more attention only because of being constantly reminded of the famous encounter between Le Corbusier and Albert Einstein at Princeton in 1946! And, of course, we had teachers who themselves were great interpreters of Le Corbusier — in design and in theory. But beyond that, Le Corbusier speaks to me rather personally too, through his provocative paintings and the fact that his mother was a piano teacher and his brother a violinist. I entered college intending to become a pianist myself, but that’s another story,” he says.

20190802_peo_pam_presidentlillian_tay_pg-8.jpg

“Rene and I were in the same class and yes, he reluctantly came to architecture after first aspiring to be a concert pianist at Yale,” affirms Tay. “We shared a lot of formative influences — Le Corbusier’s legacy being one — and many long, late nights in the architecture studio. I recall how Rene worked red-eyed with little sleep, absorbed in classical music, and always presented twice as many hand-rendered drawings as anyone else to the final jury. He doesn’t believe in doing things in small measures; likewise, his building up of this large collection of models capturing the entire works of Le Corbusier, including unbuilt ones from his early research, while teaching a course on the master at Syracuse University.”

Although Terengganu-born and Penang-raised Tan eventually settled in Singapore, he and Tay often made “pilgrimages” to the temples of Modernism upon their return from the US. “Rene would bring his young interns and architects and we travelled to Brasilia, Chandigarh, Paris and all over France to see Le Corbusier’s projects, and the works of other masters like Oscar Niemeyer and Mies van der Rohe.”

The student conundrum

Architecture demands a notoriously long period of study, often requiring seven years to complete a degree programme. Tan and Tay themselves were educated at the world’s most prestigious universities. So, it may surprise people to know that Le Corbusier himself never formally studied the discipline.

“Neither did Frank Lloyd Wright nor Mies van der Rohe,” adds Tan, “yet all three emerged giants of 20th-century architecture. I believe it was precisely Le Corbusier’s lack of formal training that opened him up to things architects from the academy could not see, liberating him from the shackles of academia and all its lessons and formulas.

“I have often told students, half-jokingly, that the worst place to study architecture is — ironically — the architecture school itself. Like Le Corbusier, we should open our ‘eyes that do not see’ and be prepared to be influenced outside of the classroom by ‘objects of poetic reactions’.

“I often remind myself never to think like an architect! Having said that, I feel it is important for young students to have other creative skill sets to enrich their architectural vision. These skills will also lead them to see beyond architecture and onto the next design idea. So, come [to the exhibition] not to fill your minds with images and models, but to open them up to the variety of ideas!”

Perhaps Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, summed up the Le Corbusier effect best when he commissioned the architect to design Chandigarh, the new capital of post-Partition Punjab, which would serve as a symbol of the New India … a city that embraced modernity and would unite its divided social classes while serving as a source of inspiration to future generations of thinkers and inventors. As the Pandit famously said: “The most important thing [about Chandigarh] is not whether you like it or not, but that it hits you on your head and makes you think.”

'LC121 Uncovering The Hand: A Journey Through Le Corbusier’s Forms' will be held until July 3 at Dewan Tunku Canselor, Universiti Malaya, and from July 14 to 24 at UAB Building, George Town.

This article first appeared on June 6, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.