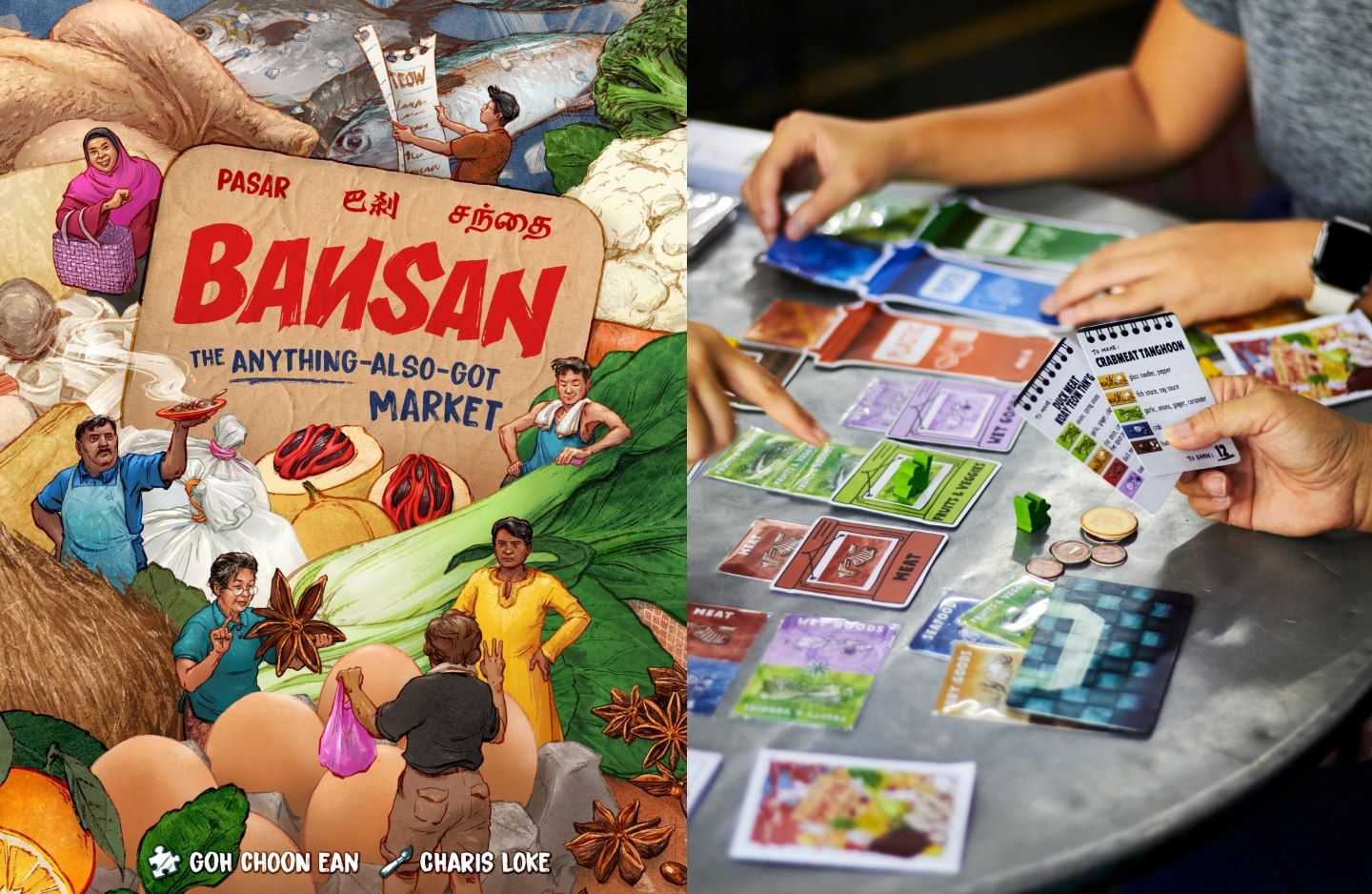

Bansan means wet market in Northern Peninsular Malaysia Hokkien (All photos: Bansan)

The wet market, or bansan in Northern Peninsular Malaysia Hokkien, invariably draws five friends to place a finger on its pulse wherever they go. “We all like to visit markets, not just in Penang but all over the world. Whenever we go to a place, we will head to the market to look at things and see how elements there reflect local culture,” says Chen Yoke Pin.

When Chen, Goh Choon Ean, Ooi Win Wen and Stephanie Kee, all based in Penang, and Charis Loke — who lived and worked there for some years — decided to inject culture and heritage into a board game, they did not have to look far: Its name and concept were right before them.

Bansan is the brainchild of media artist-cum-video producer Goh, who spread the initial sketches on her bed and worked out the mechanics and playing experience through the pandemic. The game will be launched officially on July 15 at Penang’s Chowrasta Market during the George Town Festival; July 16, Seberang Jaya Market; July 18, Air Itam Market on the main island.

Designed for one to five players, it is inspired by the multisensory experience one encounters at a bustling local market. Players are vendors who bao ka liao (take charge of everything): deal with fellow vendors, wholesalers, customers and municipal council officers; buy and sell ingredients; and cook and serve a variety of hawker stall dishes, drinks and desserts.

The gameplay follows the flow of produce that passes from wholesaler to vendor to customer. On top of this, vendors have to manage waste generated in the market from various activities. They can also take part in any of 40 Malaysian-flavoured events and prepare food to sell from 54 recipes, to increase their income and become the Bos Bansan.

bansan_main.jpg

Other game components include Event cards that resemble old calendar pages and player screens designed as Wallets used by different market characters.

“Chowrasta is the source of inspiration for the game, although Bansan is not modelled on any particular market,” says Chen, who co-produced the game with Goh.

Chen is senior manager of Arts-ED in Penang, which focuses on community-based arts and culture education. She and Ooi, who also works with the non-profit organisation, are responsible for the research and stories in the game.

Loke, who curates community storytelling projects and illustrates speculative fiction novels, created the images for Bansan as well as Kaki Lima, a tabletop game about pedestrians navigating their way through a grid of five-foot ways, which Goh designed and published in 2019.

Kee works with a social enterprise, besides managing a mentorship programme for Malaysians to create video games with social impact. Besides helping to promote Bansan, she is collating what the project team has shared and will turn them into bite-sized stories that will be uploaded online to reach a different target audience.

bansan_artprocess_prawnmaterials.jpg

“Our key target really is youth who do not have much interaction with markets. This will be a very interesting way to let them think about how food is prepared and what ingredients go into their creation.”

The stories behind the many characters in the game and the local markets around us need to be told because they are important to our cultural fabric, Kee feels.

The team hopes a bargaining element whereby players strive to get the best price for whatever they want to purchase will entice youngsters to Bansan, whose gameplay duration is 30 to 50 minutes.

Goh recalls watching a girl of about seven or eight bargain hard to get a lower price for a particular item. “It was like she owned the role of the market vendor as she tried to persuade the other player [her mother] to ‘Give me two for one ringgit’.”

Seeing different people sit down to play Bansan surprises Goh. Watching teenagers put their phones aside as they are absorbed and begin to engage with fellow players, such as their family, is “really rewarding”.

More than just ringing the cash register at play, the game is a documentation of our culture and heritage, and how collaboration, bargaining and accessibility happen in real life, Chen notes. What they have done is interpret these aspects using a scenario people can identify and connect with.

bansan-writing_tools_typeface.jpg

Loke jumps in on Bansan’s documentation of cultural heritage. “What’s important for people, young or old, is being able to see their culture represented in the media. Games are a form of media and it’s rare to see your local market documented accurately. So, as much as possible, we’ve tried to stay true to how Malaysian markets are set up.”

She points out the hooks vendors use to hang meat and snack packets, and the way produce is laid out at stalls in different plastic and metal containers. There are also gadgets that make light work, like coconut scrapers. Waste that accumulates at the market and ingredients that go into the recipes featured in the game are authentic too.

Her illustrations do not materialise purely out of imagination. Loke referenced photos and objects at markets in different places before starting on the artwork. “As an artist, I think one thing you can do for people is make art that reflects them and their culture. It’s easy to draw a generic market by pulling things from everywhere. But something generic is harder to engage or empathise with.

“Conversely, things that are specific catch people’s attention and make them say, ‘Hey, I know this stall … My uncle has one like this.’ It also reflects their culture.”

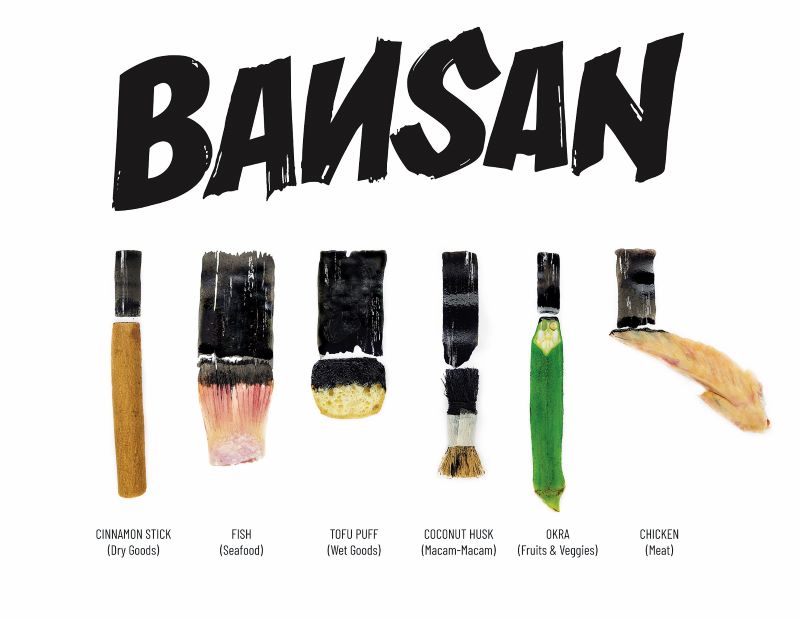

Loke combines digital illustration and printmaking to create vibrant visuals that evoke the myriad shapes and hues of the many goods and items one finds in markets. To layer in feel and texture, she collected discarded produce and waste materials from several wet markets, cleaned them up, and then utilised gel plate printing with lino ink to record silhouettes and impressions of them.

Objects she worked with include cardboard, chicken wings, fish tail, fruit wrappers and noodles. Prints produced from these became patterns and backgrounds for the game’s Produce and Stall cards and box inlays.

_mg_5203a.jpg

Goh chips in to explain how they engaged a font type creator to come up with the Bansan logo. Inspired by what Loke was doing, they used different ingredients from the game’s produce categories to “write” each letter in the logo. They then picked the best ones from a whole bunch of letters.

B-A-N-S-A-N was written with a cinnamon stick, the tail of a fish, a tofu puff, a coconut husk, okra and a chicken wing. The okra lettering was then expanded and digitised into a functional typeface and used as a display title font for the Market Stalls and Produce Cards.

She is happy with how the logotype turned out and that each letter is made from an item representing each of the six stalls in the game.

Loke admits that Bansan was a lot of work for one person, especially with the level of detail needed. “I’m also quite a perfectionist and it was very difficult for me to cut down [on the details] and do things that are passable but maybe not as good as they could be.”

She also illustrated Kaki Lima, which featured mostly Goh’s photographs and only had illustrations for the characters and scoreboard. “I don’t know if I would do it again, but it was a good experience.”

Goh’s experience with her first game will come in handy when Bansan is ready and they move on to marketing it. “We learnt the hard way with Kaki Lima. I don’t think we really thought about the selling part until we had the game.” This time, there will be distributors and game store retailers to help.

To pre-order Bansan, see here.

This article first appeared on May 15, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.