Many stories started out as a way to make sense of the world, says Heidi. The geo-mythical tales in her book explain how people in the past, who did not have access to the knowledge we have today, tried to understand natural phenomena such as earthquakes and tsunamis (All photos: Heidi Shamsuddin)

The oft-told cautionary tale about Si Tanggang who sails away to find his fortune and returns home rich and royal, then denies his old and poor mother, kept Heidi Shamsuddin up at night long after her father told it to her. It was the first time she had been completely obsessed with a story and something about it stayed with her.

Heidi’s fascination with the wonder and magic of fantastical stories grew from childhood until she hit her teens, when it became uncool to read them. So she put those books aside and went on to study law, then worked as a litigation lawyer in London before returning home to Malaysia in 2007.

Motherhood brought her back to fairy tales as she started reading them to her three children. “I would buy new books on the pretext that it was for them, but it was actually for me.” Revisiting old favourites as an adult, she saw them in a different way and also noticed details she had completely missed before.

“I discovered I never really grew out of them. In fact, they had hidden facets, which only became accessible once I had experienced a bit of life. This is what I like most about fairy tales — each person can take what she needs from a story and interpret it according to her own experiences.”

Written in the universal language of symbols and images, fairy tales are deceptively simple, short and lack any kind of description. “However, their flat, undescriptive nature allows the reader to fill in the gaps with her imagination and put herself in the shoes of the protagonist.”

Heidi went beyond that. She started rewriting a few local folk tales, keeping brief notes about the history and background of each as a record for herself. As her research expanded across borders, she noticed variations of the same stories in different countries. For example, Si Tanggang exists as Malim Kundang and Lancang Kuning in Indonesia, and Mahkota Manis in Brunei.

It also surprised her that there was no comprehensive collection of folk and fairy tales from the region, “our own version of Grimms’ Fairy Tales or the Arabian Nights”. So, she adapted and compiled 61 fables, myths, legends, folk tales, epics and wonder and magic stories from Southeast Asia and Nusantara: A Sea of Tales was launched early this year.

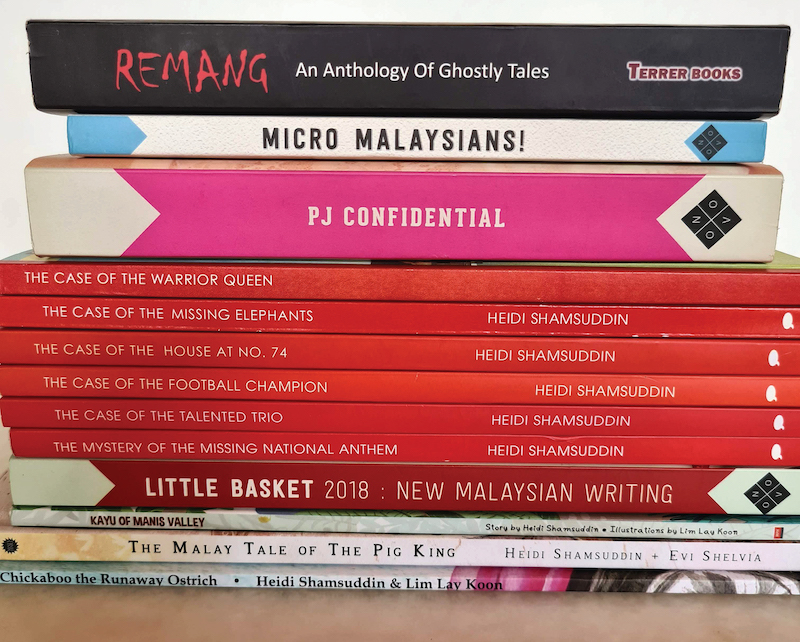

Tracking down the source of those stories, many of them folklore passed down orally, was like a treasure hunt, says Heidi, author of The Door Under the Stairs series for children, Kayu of Manis Valley, The Malay Tale of the Pig King and Chickaboo the Runaway Ostrich (illustrated by Lim Lay Koon), inspired by an ostrich that made the news running down the Federal Highway in Kuala Lumpur in June 2016. She wrote the screenplay for Batik Girl, which won Best Animated Short Film at the Festival de Largos y Cortos de Santiago 2019 in Chile, and the gold medal (regional category) at the 20th DigiCon6 Asia in Japan.

20200906_111451.jpg

On the Nusantara collection, she says: “I want these stories to move and adapt in the way they were meant to and inspire other writers and artists to use them so they will spread once more.

“I believe a fairy tale is a form of transport. Like a car or train, it transports us to other places. Fairy tales travel and move; they come from our distant past, into our present and are the stories we leave behind for our children. If we stop telling them, they will die and eventually be forgotten. But if we keep telling them in different forms, be it through print, media, art, music or dance, they will live and flourish. I am looking at new and more relevant ways to preserve and share these stories.”

Bent on that, she launched a YouTube channel, Nusantara Fairy Tales with Heidi, in January 2021. Between that month and September last year, she uploaded one video every Friday morning. To date, there are more than 41 episodes and she wants to do more, drawing inspiration from Angela Carter, one of her favourite fairy tale writers, who said: “I believe there is something in these old stories that does what singing does to words. They have transformational capabilities, in the way melody can transform mood. They can’t transform your actual situation, but they can transform your experience of it. We don’t create a fantasy world to escape reality; we create it to be able to stay.”

Moving from print to online was a completely new experience for Heidi, who figured that as the old tales she had put together began as oral traditions, the ideal approach would be to tell them in her own words and talk a bit about how they can be relevant to our lives today and how they reflect our culture. “With fairy tales, each retelling adds something new and enriches the story further.”

The technical aspects of filming, lighting, audio and putting videos up on YouTube, all of which she had no knowledge of, was challenging. Heidi watched tutorials and took classes on video editing and got help from her daughter, Layla, who set up the channel, designed the original thumbnails and even composed the theme song, her favourite part of these videos. She engaged a local artist to design her avatar — a Nusantara pirate looking for lost stories — to make the channel as attractive and professional as possible.

Heidi records the episodes in a tiny studio at home. “It was really awkward at first as you can probably tell from the first few videos. I kept looking in the wrong place, spoke too quickly and my editing was very choppy. But gradually, the quality improved and I felt more comfortable in front of the camera.”

The idea of having a YouTube channel to get the Nusantara stories out to the world came to her during the early dark days of the Movement Control Order in 2020. It certainly has. Listeners wrote in to share their own versions of what she showcased as well as resources to other stories. “One guy even gave me his thesis on a famous Nusantara folk tale called Hikayat Parang Puting. The videos have given people a lot of joy and comfort.”

20220614200707_img_1554.jpg

What amazes Heidi is how some of these fantastical, outlandish, unrealistic stories reflect her own journey through life. “These untrue stories contain some of the most realistic truths”.

In her younger days, she was drawn to tales about protagonists facing hardships that drove them to embark on journeys that saw them learn and grow. Now, she prefers those about the older woman, the witches and stepmothers, and have begun to question the reasons behind their actions.

Many fairy tales appear didactic on the surface, but dig a little deeper and you find other elements to the story, she says. Si Tanggang had her asking, How could the son treat the mother that way? Must we obey our elders in all circumstances? What if our elders are in the wrong? Why is the punishment so severe? “These questions, I discovered, were what kept me up at night when I was a child.”

Heidi is working on a second volume of tales from the Nusantara, which will include more stories outside of Malaysia, and is slowly categorising them so people can easily locate their origin.

Last September, she stopped her weekly video uploads to care for her mother, who fell ill, but still does it when she can. Lately, the author has been experimenting on producing an audio version of the stories, as well as the idea of doing podcasts.

“When we listen to fairy tales, our soul is invited to journey into a place of horror and violence, as well as enchanting rescues and romances. They assure the listener that while evil, danger and violence do exist, they can be transformed. By entering into the magic of a fairy tale, we can find strategies for navigating the hardships life presents us with. This is why I love them,” Heidi says.

This article first appeared on June 27, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.