Saloma, Tan Sri P Ramlee and Tunku Abdul Rahman (Photos taken from Rosalie and Other Love Songs)

As the reverberations of Tunku Abdul Rahman’s cries of “Merdeka!” died down, as flags and streamers were cleared away, Radio Malaya’s Alfonso Soliano was told that the new Federation of Malaya needed an orchestra. Not just a dance orchestra; a proper symphony orchestra, with trumpets and clarinets and a large string section and a harp, befitting a nation about to take its place on the international stage.

This was a tall order in Kuala Lumpur, where musicians played mainly in nightclubs and the entertainment world. From these places, Soliano and music producer Ahmad Merican plucked them. The musicians were agile, able to improvise for hours, they had “chops”. But there was a major problem: few could read music.

This was one of Alfonso Soliano’s finest moments. To ensure they got through Radio Malaya’s auditions, Soliano helped the musicians learn the music by heart, so that at the auditions, they could pretend to read the scores. Once in, he set about teaching them how to read, note by note, cadence by cadence. Slowly, against all odds, an orchestra came into being, with perky saxes and mellifluous woodwinds. Compositions were written, rehearsals held. Musicians from the Federation Police Band, led by another extraordinary musician, Alias Arshad, augmented the orchestra. In under two years, the massive task of creating an orchestra from scratch was achieved. Its debut concert, Malam Irama Melayu, was held on Dec 2, 1959, at Dewan Tunku Abdul Rahman. That night, the privileged audience heard soaring crescendos, majestic timpani, brassy walls of sound. It was a triumph, of determination over lack of education.

As the years rolled by, music schools sprang up, more orchestras came together, and Malaysian music-making muddled along. Wealthy and middle-class children received formal musical education, as always. (The redoubtable lawyer P G Lim recalled not one but three pianos in her home in Penang.) But across the country, the average primary school pupil remained musically illiterate. There was never a convenient time to introduce music education into our public schools.

Which is curious, because music has always been a part of our country’s story. As we recovered from the hardship and depredation of war, music helped us back on our feet, leading to explosions of joget moden and Latin-infused dance music. As our politicians criss-crossed the peninsula rousing the people towards independence from the British, musicians such as Achmad C B went with them, writing fiery anti-colonial songs to whip up sentiments at political rallies. In 1956/57, during the intense months leading up to Merdeka Day, Tunku Abdul Rahman spent precious time overseeing a worldwide search for our national anthem and the creation of our first batch of lagu kebangsaan. When, in 1963, Indonesia threatened war against newly-born Malaysia, stirring patriotic songs such as Perajurit Tanahair, broadcast often on Radio Malaysia’s airwaves, played an important part in the psychological warfare between the two countries. (In 1997, after Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim’s sacking, this song was also heard on Dataran Merdeka as people chanted “Semboyan telah berbunyi/ Menuju reformasi!”.) When Konfrontasi was declared over, the song Berjaya by the master songsmith Saiful Bahri @ Surya Buana rang out on our airwaves. It earned such a place in popular memory that, when Malaysia won the Thomas Cup decades later and the crowds in Stadium Negara spontaneously burst into song, it was that song they sang.

In different times, Malaysians have sung other songs in unison, vociferously, with defiance, as water cannons turned the corner and batons met protestors’ skulls. Under even darker clouds, as the country hosted the SEA Games in 2017, it was music that illuminated the games’ opening ceremony and revived national pride, albeit briefly. And how will we ever forget one emotional night in May this year: how many voices, belonging to how many tribes in how many parts of our country, sang “Negaraku/Tanah tumpahnya darahku”, with emotions impossible to express otherwise?

As a nation, we are musically mute, because the vast majority of us were never taught how to sound our voices, to write our inspirations down, to express the music we might otherwise make

GE14 this year was monumental. Amid the euphoria, no one has any illusions that it will be plain sailing. Beyond governance challenges have arisen larger, more abstract matters: moral complexities, the effect of past crimes on the national psyche, identities being rapidly renegotiated and transfigured. Yet our hearts feel lighter, and again as at Merdeka, we embark on uncharted waters with optimism and hope.

This would be the time to reach into ourselves and sing our music. But what is that music? We do not know. Music schools teach the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music’s syllabus, sporadically there are classes on Chinese and Indian classical music and cool kids dabble in electronica. The child in Terengganu tinkering with a gamelan set could imagine a world of different possibilities, but it takes more than just imagination to move beyond Malay gamelan’s century-old repertoire. We have innovative people who could teach that child and equip her with tools, but the connections are not being made. Elsewhere in Malaysia, music-making consists of a handful of guitar chords, banging drums and singing, because that is what comes easiest, without education. Maybe later, that kid from Terengganu might go to Akademi Seni Budaya dan Warisan Kebangsaan (Aswara) and learn the rudiments of music. Or, perhaps later, she will teach herself, watching YouTube. But the youth who learns music at 20 does not have the facility of a child who is taught to expand his musical mind at six. As a nation, we are musically mute, because the vast majority of us were never taught how to sound our voices, to write our inspirations down, to express the music we might otherwise make.

Given this national scenario, top-down initiatives such as PERMATA have little chance of working, or will benefit a very few. In the Dewan Filharmonik, Lutoslawski has given way to Datuk M Nasir — a more realistic representation of our musical exposure. So, in this respect, since Merdeka, Malaysia has not developed. And so at rallies and national concerts, songs sung are from the 1950s and 1960s. Fans of Malay pop confide that Indonesian bands are superior. When asked for a national music icon, Malaysia still cites P Ramlee, whose heyday was in the 1950s. If the public were to be asked what kind of modern music binds this diverse nation, the frank answer would have to be K-pop.

Poignantly, as if unaware of this stagnant milieu, many attempts have been made to promote “Malaysian” music. Here lies pathos. What does Malaysian music sound like when it is not officially sanctioned forms of traditional music nor hip hop nor heavy metal? Is it something you can resolve into existence as a matter of policy? Culture officials and branding agencies seem to think so, and crunch angklung, tabla, erhu and sometimes a hapless sape together in hubristic soundtracks. Over the years, this sort of “fusion” has met with little success (and resulted in some ghastly manifestations).

Far more organic and vibrant is young Malaysians’ interest in questions of identity and social history. Every day, social media publicises events on topics such as religions predating Islam, communities’ traditions and rituals, flaws in official histories and historiographies, morphologies in architecture. Helped by thinkers such as Jomo Sundaram and Farish Noor and iconoclasts such as Hishamuddin Rais and Kassim Ahmad, young people want to find out for themselves, question what they have been told, determine their own identities. This needs details. What is the difference between Chitty and Chettiar, why do Straits Chinese look down on Chinese who arrived later, what about the Jews, Sufis, Armenians, Gujeratis, Japanese and Russians who lived among us and whose blood possibly runs in ours? It has taken a long time, but finally we are climbing out of the colonial boxes of “Melayu, Cina, India dan lain-lain”. And increasingly books are being written, films being made, that take us towards a more nuanced understanding of our many ethnicities and hybridities, complex heritage and multiple narratives.

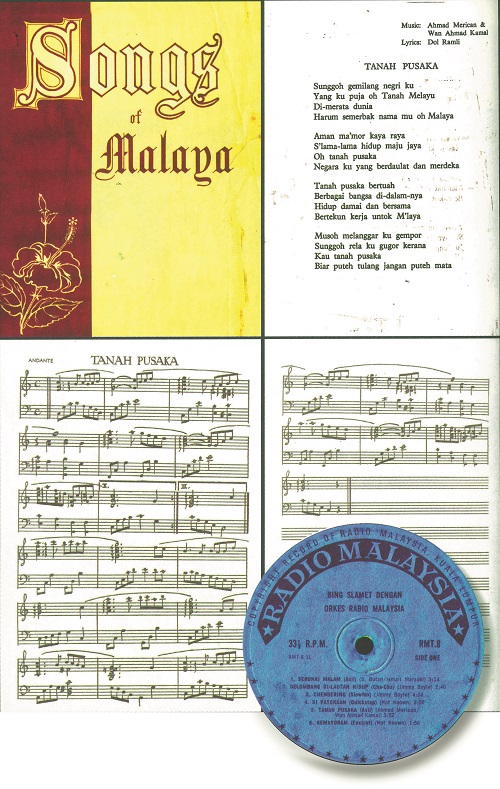

Dol Ramli with music by Tan Sri Ahmad Merican and the late Wan Ahmad Kamal

The story of Malaysia is not just one story, told by those educated enough to write it. The story of Malaysia is a million stories, waiting to be told. So, too, the music of Malaysia. So who will voice the musical impulses, the polyrhythms and melismas of a modern Malaysian Malayalee, a young Malaysian Hakka, a passionate Malaysian Bajau and Melanau and Bugis? Our music teachers are not trained to teach this. That syllabus does not exist. But if today we help young minds see more musical possibilities, teach them larger musical vocabularies, they might in time express it.

The evidence points to fertile ground. Having said that the state has done little for music, stars have emerged anyway. To speak of only one genre, out of many: in contemporary composition, there is Kee-Yong Chong (who worked as a plongeur for two years in Brussels to pay for his studies at the Conservatory and later won international prizes so regularly that he was called a “professional prize-winner”), Tazul Tajuddin, Yii Kah Hoe, Tengku Ahmad Irfan (also a superb classical pianist and conductor) and Chow Jun Yi. They are outstanding, not just technically, but because of their compositional idiosyncracies, shaped by where they grew up and their socio-cultural influences. These are the few, shooting stars whose internationally acknowledged brilliance and authenticity underline all the more the tragedy of their neglected peers.

Sixty-one years old and a nation reborn. As our leaders shape shiny new policies for Malaysia Baru, we must press them to give our children basic music education at an early age. The country is too old for this nationwide illiteracy. It is not acceptable to say that Malaysia is RM1 trillion in debt and, therefore, the arts must take a back seat. Despite music’s importance in our national narrative, despite the uniqueness of Malaysian musicians, music education in this country never had a seat in the first place, it was never at the table, it never even got into the room. Politicians will come and go, each with their notion of what is best for our economy. Priorities will evolve. But there can be no further excuse to keep our young ones in musical ignorance. Give our children the rudiments of music and they will create sounds richer than we could ever have imagined. And yes, maybe somewhere along the way, “Malaysian” music will come to be.

This article first appeared on Aug 27, 2018 in The Edge Malaysia.