Burns' poetry ranged from sloganeering to the tender and created a complex poetic personality.

A close friend of my father’s — Thor Ghim Lock (Uncle Ghim Lock to me) — bald, straight-backed, deep-voiced and always with a cigarette, worked at the Oxford University Press offices in Kuala Lumpur. As shipments of that illuminating series — Oxford World’s Classics — arrived every few months, he would carefully set aside a box to bring them to me, a scrawny child with a touch of the inner wild but always tentative when among people.

Growing up in a new neighbourhood lyrically called Pantai Hills, carved between the new popular township of Petaling Jaya and the heart of the city of Kuala Lumpur, life was the vast outdoors — overgrown, craggy, snake-infested, with tadpole-catching in the now submerged Damansara stream down the road as a sport — or the deep interiors of my single room, proverbially buried in books.

I can still remember ripping the tape off the first box and discovering She by H Rider Haggard — an adventure story, apparently for boys. A decade later we would discover a version of this adventurer Horace Holly, its protagonist, in the form of an archaeologist called Indiana Jones. There were volumes also of a new series called the Classics of Asia Series, which featured the tales of Hang Tuah, carefully retold by Mubin Sheppard, and the immortal story of Lady White Snake. There was Kipling’s The Jungle Books, which would later lend me my first literary archetype — Mowgli, the Jungle Wolf Boy.

Then, there was, especially, the gasping Scotsman Robert Louis Stevenson, prone to pneumonia, who dreamt always of a tropical climate that would make breathing easier — and with that dream of good breath, unfurled the fantastical landscapes that would forge his classic novels and stories Treasure Island and The South Sea Tales.

rtr1kqwg.jpg

My best-loved of his books, however, was Kidnapped, set within the valleys of what was then for me the fabled city of Edinburgh, with its castle ruins, rebellions and first clipped syllables that bore my very name. It was also my earliest introduction to what would prove a lifelong intellectual fascination — radical politics.

The setting of Kidnapped — the aftermath of the Jacobite Uprising — inspired a sense of keen discovery in me. Troubled even then that such an interest might bear the traces of a benign colonialism, I reconciled in my head that loving the Scots was better than loving the English and so retain, to this day, a quaint partiality for Scottish independence. This trail of discovery was to lead to a deep search of Scottish history through the pages of that greatest educator the Encyclopedia Britannica, a discovery of Macbeth and finally to the histrionic figure of the poet Robert Burns.

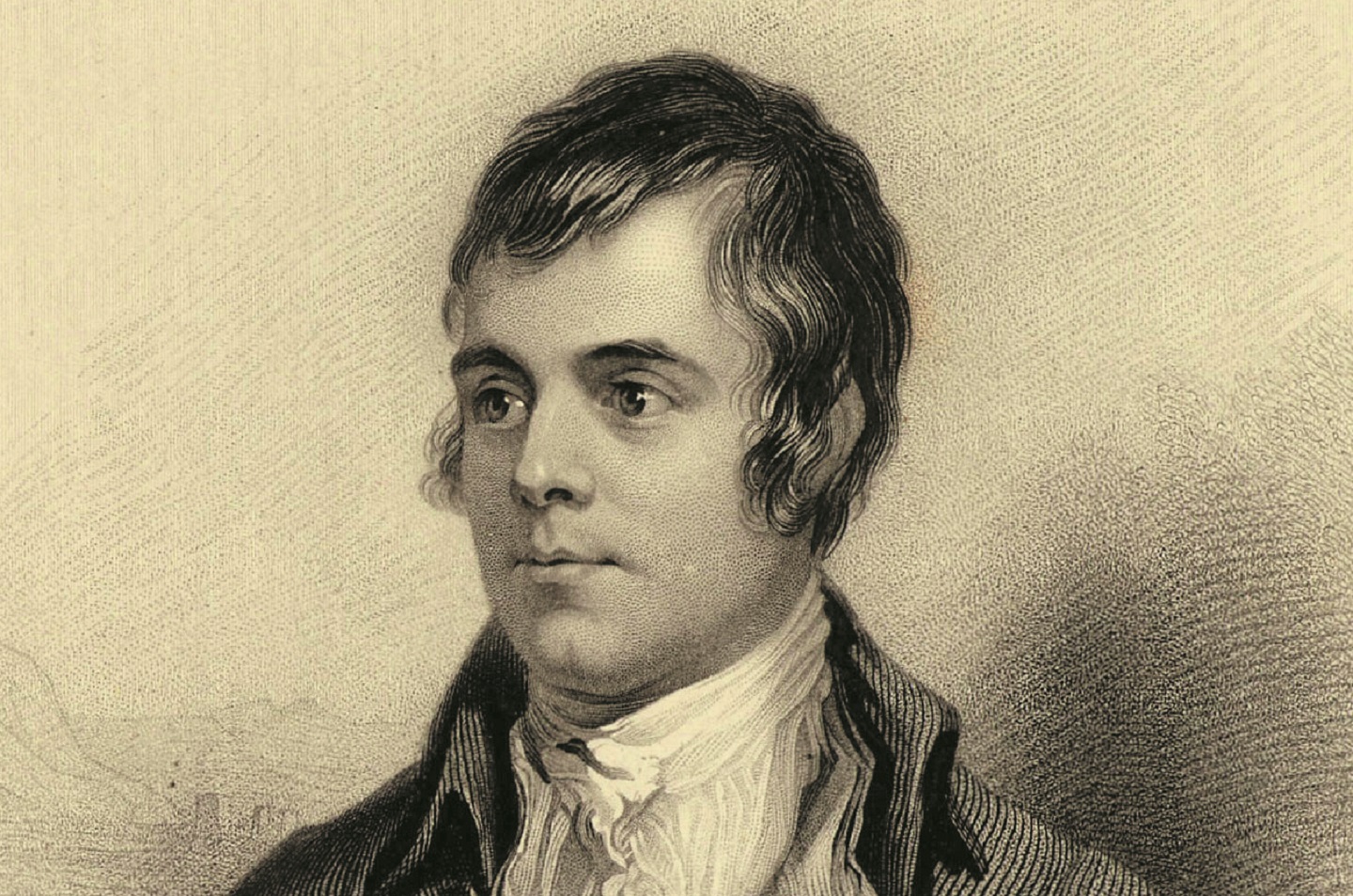

This mythic figure of everything Scotland has suffered the fate of most myths — a deflation of real meaning and a mutation into national sentimentality. Even today, the real radicalism of Burns would spark contentious debate.

Born in Alloway in Ayrshire, Burns, the son of a tenant farmer, grew to his radicalism watching his father beaten by authority. His radical ideas burned with the onset of the French Revolution and its promise of “liberty, equality, fraternity”. His poetry ranged from sloganeering to the tender and created a poetic personality of such complexity that he has since become everything to just about everyone. As the Scottish poet Don Paterson described, “Whatever you want to see, you’ll find: a crude boor and brilliant raconteur; a male chauvinist pig and a champion of the rights of women; an Ayrshire farmer and an Edinburgh sophisticate; an abolitionist and a supporter of the slave trade (he almost left Scotland to work on a plantation in the West Indies); a bad English late-Augustan poet, and a brilliant Scots early Romantic.” Or, in the words of one of Burns’ own songs, “Man is complicated”.

Yet, this maze through the Britannica and the labyrinth that is Scotland Robert Burns struck home when I discovered that the song Auld Lang Syne — long regarded as a family anthem at every whisky-driven New Year’s Eve, here and everywhere — was put together by the very same Robert Burns.

Declared by the BBC as an “international anthem and Scotland’s greatest gift to the world”, Burns’ Auld Lang Syne — a song of the deepest sadness, longing and dreams of reconciliation — was brought by the Scottish immigrants throughout the diaspora, especially to the regions of North America.

It is rumoured that in the American Civil War, the general of the Unionist armies, Ulysses S Grant, restrained the song from being sung by his cavalry for its theme of home and return would induce homesickness. But upon victory, he ordered the band to play it as a symbol of hope and healing. By the 20th century, the song had become a recurrent theme for renewal in silent cinema, used most poignantly by Charlie Chaplin in the New Year scene of the film The Gold Rush.

Closer to home, a striking recollection by Anthony Burgess in his memoir Little Wilson and Big God of a drunken New Year’s Eve night in Kota Baru — overlooking the Kelantan river, on the eve of a Malaya headed for independence, with his great novel The Clockwork Orange looming — has loud voices in the background announcing departure by singing Auld Lang Syne.

“I think that the reader should enrich what he is reading. He should misunderstand the text; he should change it into something else,” the greatest of our readers and one of the greatest writers, Jorge Luis Borges, once said.

It is how the misunderstanding of Burns’ Scotland and Auld Lang Syne takes place: I am five and six and seven in the midst of a swirl of bodies also driven over a little by whisky. We are mimicking a Scottish dance step. My gentle uncles are, in this instance, slightly boisterous. We have struck the turn of year. It is my beautiful mother’s birthday. An uncle’s hand reaches down and hoists me over his shoulder, and the song begins, Should all acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind…”

It is one of my clearest memories — this sense of great height.

Eddin Khoo is a poet, writer and translator as well as founder and director of Pusaka, a cultural organisation.

This article first appeared on Dec 23, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.