The City and Its Uncertain Walls is Murakami's 15th work (Photo: Haruki Murakami)

Haruki Murakami wears all kinds of shoes that are not his. Some days, he slips into the role of a 15-year-old runaway fleeing from an Oedipal curse. Others, he traces the footsteps of a cat whisperer in a village where stray felines are delegates of another realm, or walks the path of a bohemian lass who discovers a romance so intense with another woman that it is likened to “a veritable tornado sweeping across the plains”. The Japanese novelist, who has written perceptively of budding infatuations and the vagaries of adulthood, calls the act of inhabiting others — some of which are projections of himself — a wonderful right and sensation that only a writer can taste. But even a master storyteller can overplant in his fallow field. The characters he has cultivated throughout the years, each performed to his patented shtick of shuttling radically between dreams and reality, are growing repetitive, as evidenced in his 15th work, The City and Its Uncertain Walls.

To be fair, the book’s elegiac and occasionally hackneyed quality is perhaps inevitable, considering its origins. Murakami’s eerie new release, his first in six years, began as an attempt to rework a 1980 novella originally published in the Japanese magazine Bungakukai. It was never allowed to be reprinted, however, because the author felt it was too raw and immature, a dissatisfaction he described as a “small fish bone caught in the throat”. Five years later, his maiden attempt at a revision developed into a jumping point for Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, a futuristic tale chronicling a garrulous man who ascends in an elevator to a corridor where a woman escorts him to a closet, at the bottom of which is a chasm with a river running through it. Only 35 years later, when Covid restrictions and our social pause began in earnest, did Murakami revisit the material and expand it into a tripartite novel that has been translated into English by Philip Gabriel.

In typical Murakami fashion, people and things in The City are moved around a chessboard of mental twists and shifts in a non-linear manner. A serendipitous meeting at a school awards ceremony draws a nameless narrator into the orbit of an eccentric 16–year-old loner struggling to distinguish her subconscious from real life. On a bench, secrets, kisses and saccharine promises are exchanged: “I was so taken by you, I thought of nothing else when awake,” confesses our protagonist, who falls tragically in love. The all-consuming summer affair between the two misfits, however, is cut short when the girl admits that she is, in fact, a wandering shadow whose corporeal self works at the library — stocked not with books but old dreams — in a city confined by high walls. Should the boy reach the real her, he could become the Dream Reader, tasked with reciting and calming the library’s dreams, lest they acquire the power to break free and bring destruction to the place. The only catch? She will not remember him at all.

The narrator alternates between episodes of his actual-life relationship as well as his experiences in the mystical city, which he does indeed reach, and where he encounters the girl again — except she is still 16 and has no memory of him. But no matter; our lovelorn man is simply pleased to reenact scenes from the past, spending time with her, sipping tea and reading the orb-shaped dreams nestled in this fantastical, yet ensconced, library.

The book is not hesitant about reminding anyone that its titular walls are viewed as a metaphor for the worldwide pandemic lockdown, and on an emotional level, the shield we put up to hide our vulnerability and insecurities from another human heart. But things are never that simple in the Murakami-verse: In this impregnable town not unlike a Hotel California situation, a strict Gatekeeper separates people from their shadows, grumpy unicorns roam the streets, clocks lack hands and towering sentient barriers realign themselves to contain the population. The tragic teen love unfolds across several chapters but, unfortunately, as the meetings between the pair become fewer and further apart, the girl suddenly vanishes without any explanation.

murakami.jpg

This lengthy arc, covering one-third of the chunky chronicle, is a throwback to Hard-Boiled Wonderland, but after this, the plot diverges from its source material. In the second and third parts, having found a method of escaping from the sequestered town that is idyllic and a jail, our narrator is snapped back to his “real” existence. Now in his mid-forties and fully grown into the standard Murakami hero — listless, jazz-loving and encumbered with spotty romantic histories — he impulsively travels to a mountainous area in Fukushima Prefecture to take a job in yet “another” library. There, he meets Mr Koyasu, a gentleman in his 70s wearing a navy blue beret and a skirt, as well as other people who, through more perplexing occurrences, subtly guide his way back to the walled-in city.

We cannot shake off the sense that Murakami has presented the book’s leitmotifs — isolation, the gratuitous mentions of cats and chests, and strange women who depart as suddenly as they materialise — better elsewhere, say, Kafka on the Shore or Sputnik Sweetheart. But The City, a creative impulse carried across decades, feels decidedly more pensive, as if the author is addressing his own journey: a literally stumped Mr Koyasu reflects Murakami’s writerly insecurities; Yellow Submarine Boy, another antisocial teenager with a savant-like memory, also entranced by the town in the book, mirrors his penchant for the Beatles and ferocious reading habits. Murakami’s novels, once whirlwinds of youth’s reckless wonder, have taken on a slower, more introspective gait as his late-career works resist the sharp edges of resolution. His protagonists, like their 75-year-old creator, no longer hunger to conquer their fates but instead seek delicate reconciliations — with lost time, guilt, grief or closure for relationships that ended abruptly. Ultimately, it matters less whether our decisions are guided by choice or destiny, as long as we can make peace with that ambiguity.

The fundamental and ghostly mysteries in The City, akin to a Möbius strip of the past and present intertwined, remain unanswered. A frustrated reader may be left wondering, “Where do our real selves exist?”, “Are we really living in the real world?” and “Why did Mr Koyasu’s wife leave two long, thick, splendid scallions in his bed and disappear?” There is no definite conclusion anyway, as Murakami wants his readers, as usual, to pick up on the hints and each arrive at their own, unique ending. The novelist perpetually leaves us uncertain of how firm the ground beneath us is, but it would have been helpful if certain details were fleshed out to provide context (What are those library dreams about?) rather than rhapsodising about events that lead to a fruitless chase.

In the novel, there are pointed references to Gabriel García Márquez and Marcel Proust, but Murakami, though an expert in melancholic and phantasmagorical narrative, evokes merely a scant trace of their magical realism flair. Nonetheless, his works may prove popular in times of political anxiety, as their sedative effect can feel like a comforting refuge from the physical world and its extremes. The universe is abidingly strange, Murakami’s allegories seem to demonstrate, but the nightmares will one day end. Coming to terms with life’s unresolved nature may be the closest we can get to a satisfying ending.

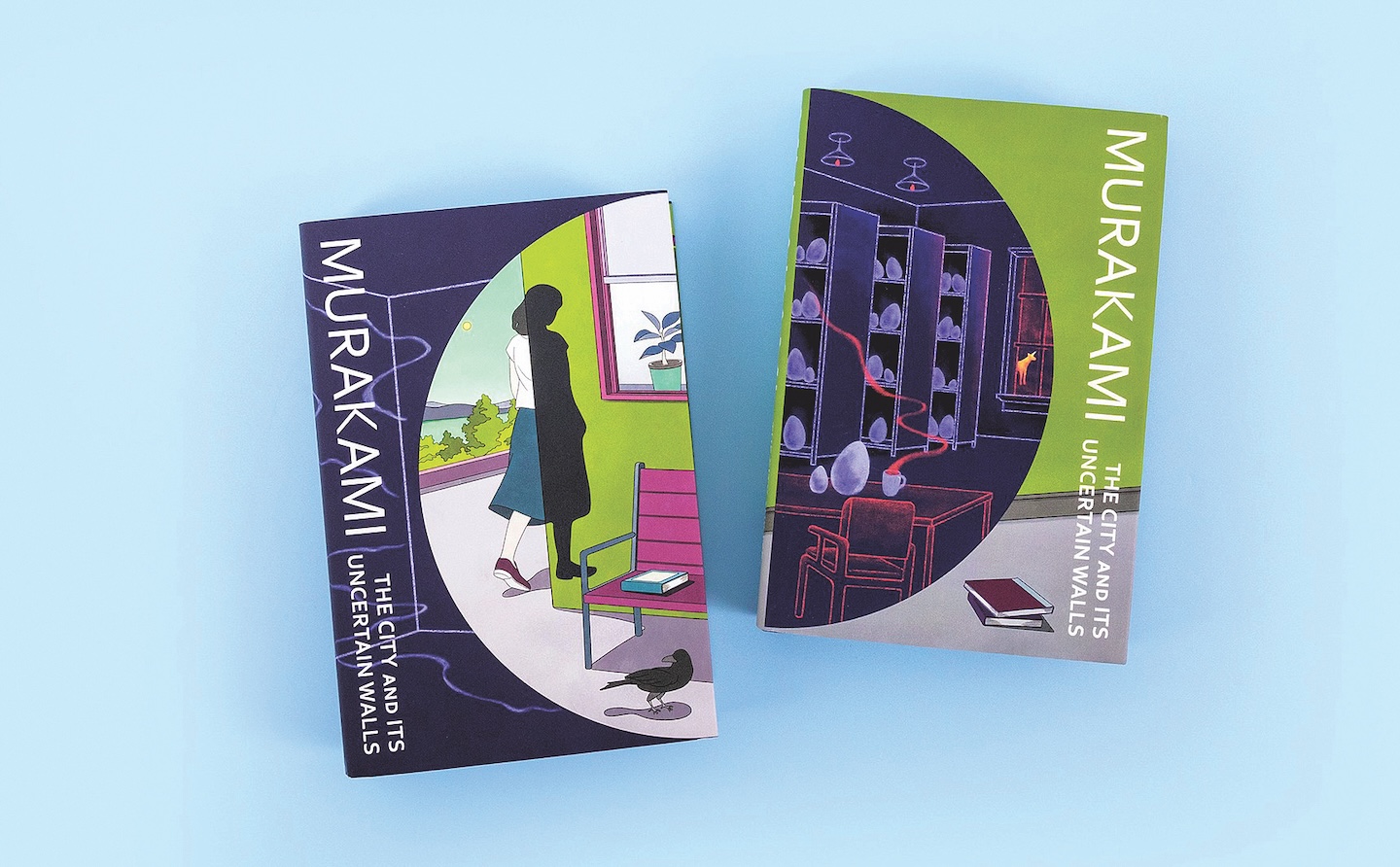

'The City and Its Uncertain Walls' (RM149.95) is available at Kinokuniya Bookstore, Suria KLCC.

This article first appeared on Dec 23, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.