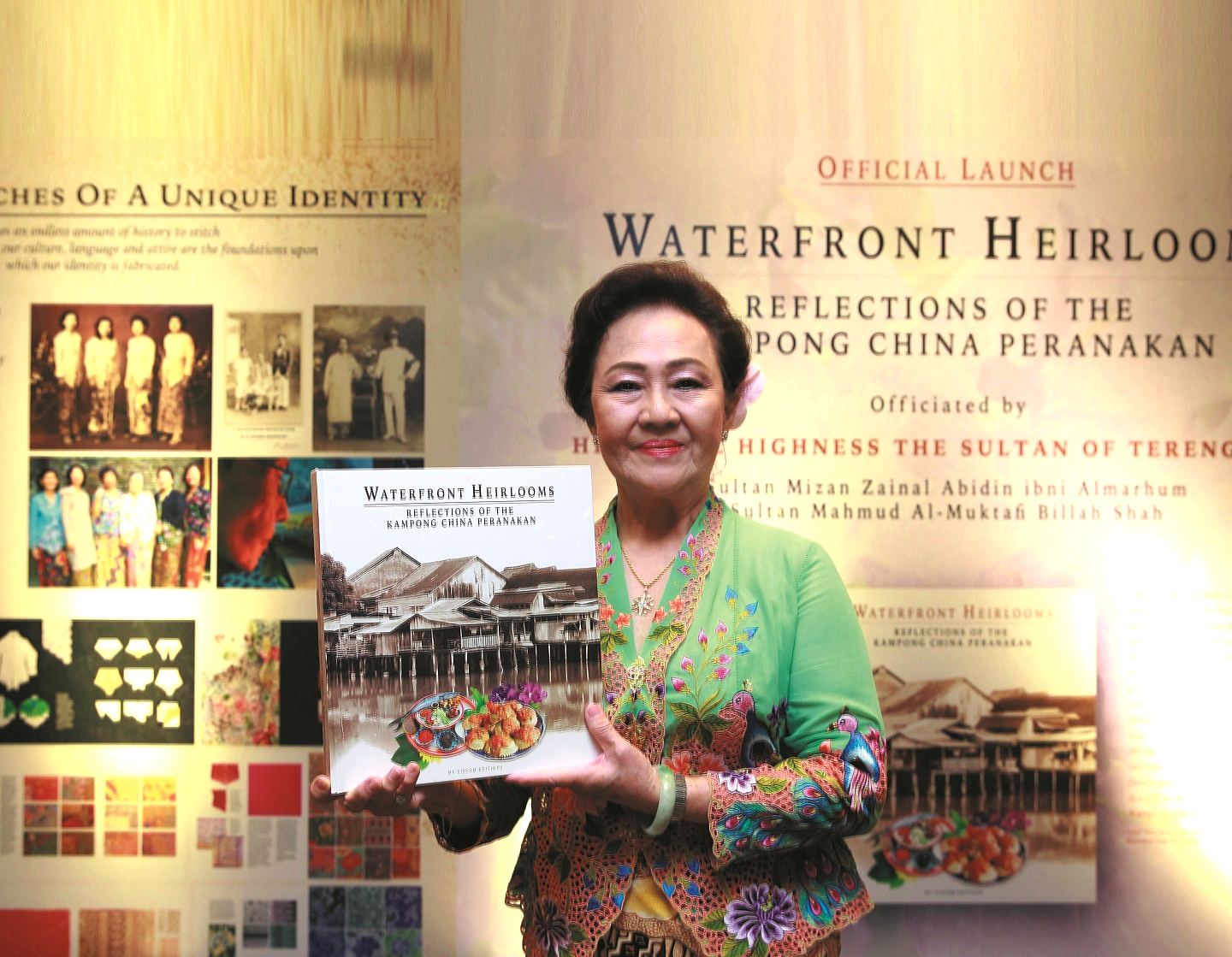

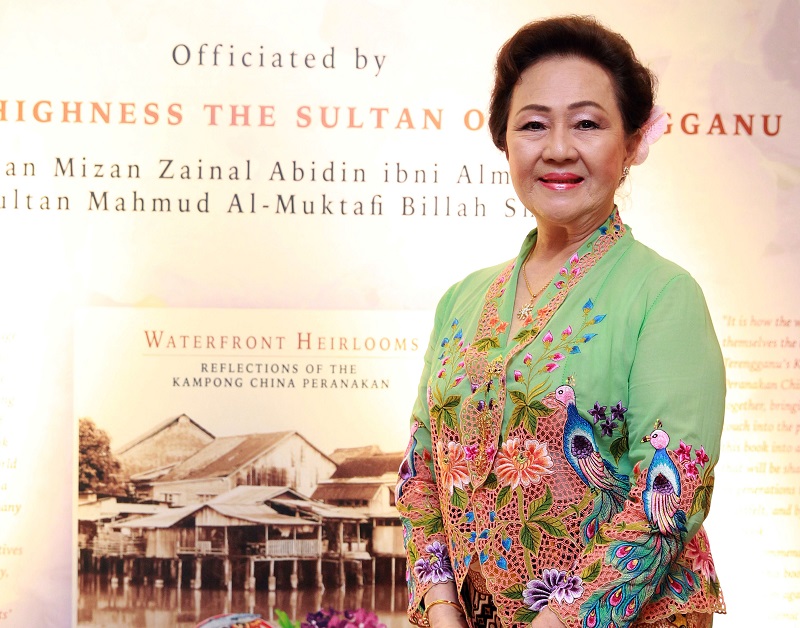

Missing home and family fertilised Rosita's desire to collate Waterfront Heirlooms (Photo: Shahrin Yahya/The Edge)

“Time is not on my side and I’m going back to my roots after 53 years. I left home and my Chinese family to get married at 19. What does a girl of 19 know about culture or anything?”

These words, spoken softly by Rosita Abdullah Lau, sum up her eight-year journey of looking back to her birthplace, Kampong China in Kuala Terengganu, where home was by the Terengganu River, a lifeline to the villagers and a playground for the children.

Rosita likens the research and hours spent gathering and talking to those still living in or are from the old village, where the oua hai (Hokkien for riverfront) houses with liam boey (timber decks) built on stilts at the back have been demolished and parts of the river reclaimed to a marathon. She has crossed the finishing line but instead of a trophy, she holds up Waterfront Heirlooms: Reflections of the Kampong China Peranakan, launched by the Sultan of Terengganu in Kuala Lumpur on July 6.

20190731.jpg

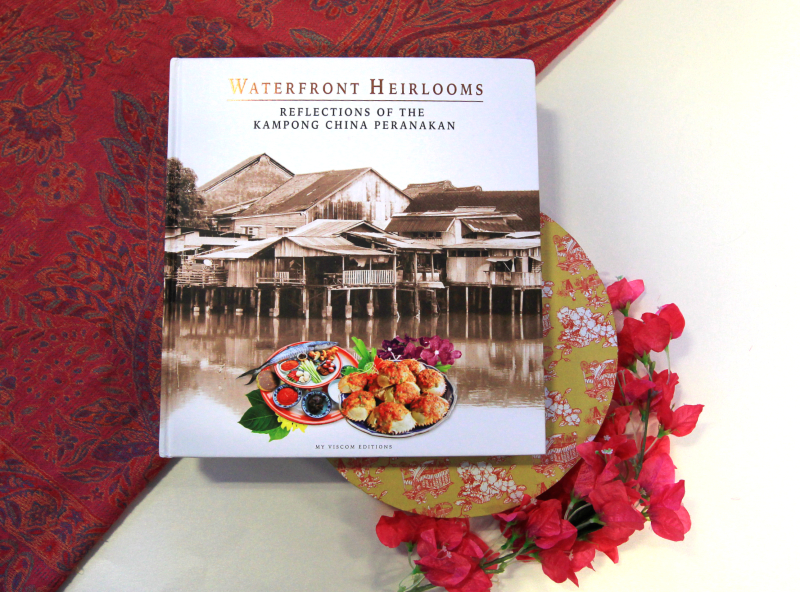

The 288-page book is a nostalgic, colourful and revealing record of the cheng mua lang (sarong-wearing community, as the Terengganu Peranakan refer to themselves), spread over five chapters: Footprints to a Legacy; Recipes to a Culture; Defining Stitches of a Unique Identity; Homage to Heaven and The Cycle of Life.

In the Introduction, Rosita talks about growing up in Kampong China, where the two rows of houses facing the 800-metre main road have distinct characteristics because one is oua hai and the other, oua sua (on the hill side). Her home was on the former and she remembers looking for oysters and crabs and soaking in the river of joy and abundance until the skin on her fingers puckered, and her grandmother and paternal aunt drawing fresh water before the rising tide turned it saline.

Kampong China, or Teng Lang Poh (literally, Chinese Village), was gazetted as a heritage site of Terengganu by the state government in 2005. Waterfront Heirlooms, published by Rosita under My Viscom Editions (registered in Malaysia under her and her son, Tengku Zainal Abidin), traces how the pioneer Chinese settlers made their way to Kuala Terengganu, the emergence of the Terengganu Chinese Peranakan — “descendants of male immigrants who came from China as traders and labourers as early as the 17th century and married local Malay women”, their culture, characteristics, patios, food, attire and identity, as well as festive celebrations, customs and traditions.

12.jpg

Captivating photographs — many in black and white — of the façades and interiors of old homes, people whose families lived in Kampong China for generations and have stories to share about pastimes and practices, recipes passed down by great-grandmothers, master embroiderers talking about the lost art, family shots and group pictures of dainty women clad in different types of kebaya and the rites, rituals and supersititions surrounding ancestor veneration, filial piety, birth, life and death — all these reflect the soul of a village that may soon remain a memory.

The tome on legacy and built heritage is enlivened with personal accounts by villagers who continued to have a special place in Rosita’s heart after she married into the Terengganu royal family, where she raised four stepchildren and three of her own.

Born Lau Yam Hong in 1946, the eldest of barter trader cum rubber estate owner Lau Beng Ann’s three children, Rosita, who now lives in Kuala Lumpur, says commitment to her new life meant she never got to sleep over in her old home after marriage. It was destiny, she thinks, which has led her full circle because missing home and family fertilised her desire to collate Waterfront Heirlooms. “I want to give back to my Kampong China. I love [the people]. They also loved me. All of us are slowly going. This book has so much soul. My soul is inside.”

The book has its seed in Kulit Manis: A Taste of Terengganu’s Heritage, also published by My Viscom Editions, in 2009. Kampong China is one of its six chapters, the others being Peranakan cultural heritage, food, architecture, handicrafts and conservation. The book, which packs 88 recipes shared by relatives, friends and food makers from Terengganu, was chosen the World’s Best Local Cuisine Book 2010 at the Gourmand World Cookbook Awards in Paris.

20190706_peo_rosita_abdullah_lau_1_msy.jpg

A year after that, gripped by “a serious case of nostalgia for Kampong China and this deep need to return to my roots and find out about our Peranakan culture”, Rosita broached the idea of Waterfront Heirlooms to May Chua and Sylvia Tan of Viscom Design Associates, the Singaporean designers who were the prime drivers of her first book. “They must have thought, ‘What is there to write on that one chapter?’ But they never gave up on me,” she says.

The project dragged because there were hardly any written documents to anchor it to. But Chua and Tan had visited the British National Archives to do research for Kulit Manis and extracted a lot of information on Terengganu, which proved useful. In the end, a good part of Waterfront Heirlooms comprises oral interviews, which colour the engrossing narrative.

“We had no bearing when we started — how to get the materials?” Rosita recalls. “I don’t think people believe in having a book. And no one takes much interest in conserving our culture.”

But funding proved the biggest challenge. “You get to know a lot of people when doing a book. Rich people do not part with their money. I had to beg for money. I am not ashamed to say it: I sold a piece of land my father gave me to fund the book. I didn’t have that connection with my family after leaving home. Now I have this book. I think Pa is smiling up there.”

Waterfront Heirlooms: Reflections of the Kampong China Peranakan is available at Kinokuniya for RM250. Buy here.

This article first appeared on July 22, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.