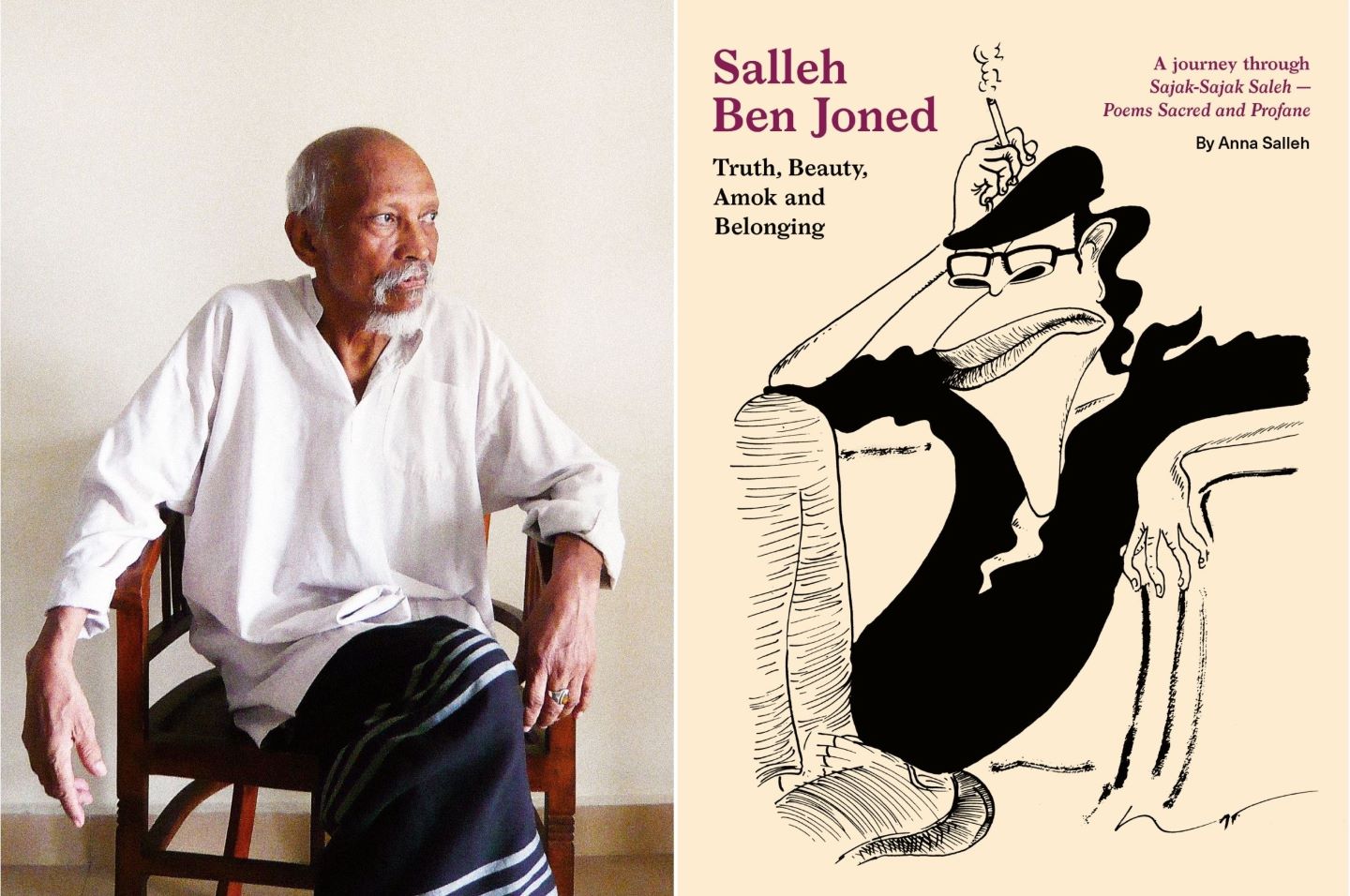

Malaysian poet Salleh Ben Joned (Photo: Hawa Salleh)

Long before her father’s death in 2020, Anna Salleh realised Salleh Ben Joned had contributed something quite special to Malaysian literary and cultural life despite being sidelined by mainstream circles for writing about fake piety, dogma and taboos, ecstasy, sensuality and more. Curiosity piqued, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) journalist started recording interviews with him and those who knew him well.

Anna read academic writings that discussed Salleh’s work and engaged with younger writers and artists influenced by him. She did research in Hobart, Australia, where he studied and lived for over a decade from the early 1960s, digging through the archives of the University of Tasmania’s student newspaper, of which he was an editor.

Her efforts culminated in A Most Unlikely Malay, a two-part podcast series for ABC released in September 2020. A month later, on Oct 29, Salleh, 79, died. Looking at the outpouring of tributes to him, Anna knew her work was not done: While her documentary was an emotional story about his personal life, from a daughter’s perspective, there was little about his works.

Then, close family friend Sheila Rahman-Natarajan suggested doing a collector’s edition of Salleh’s first book, the bilingual poetry collection Sajak-Sajak Saleh: Poems Sacred and Profane. Over time, the book grew into something much more.

“It became an exploration of my father’s literary journey via a selection of his poems, prose and photos,” says Sydney-based Anna, who was in Malaysia recently for the launch of Salleh Ben Joned: Truth, Beauty, Amok and Belonging. “Another important component was stories about the people that inspired him and who, in turn, were inspired by him. Again, I was the narrator.”

Late last year, she spent two months in KL collecting and processing archival material to include in the book. The trip enabled her to meet people face to face, “so important when you work largely remotely”. To give herself headspace for the project, Anna took extended leave from the ABC, where she works three days a week as an online journalist, and gave up her regular Brazilian jazz performances.

c_2006_sbj_and_anna_in_sydney.jpg

Knowing that Salleh lives on in the hearts and minds of the younger generation, artists, poets and students drives her to curate his legacy. “I’m particularly fascinated by the way young Malays in theatre and literature have been embracing him after he was essentially shunned by the Malay literary establishment for so long.” She includes their voices in the book.

Recent events have heartened her, too. In October, Aswara (the National Academy of Arts, Culture and Heritage) staged in full, for the first time, Salleh’s only published play, The Amok of

Mat Solo. An editorial in Dewan Sastera declared that his “truly liberated writings energised Malay literature and showed what was to be appreciated in forms like pantun”.

Anna’s project had its bumps. At the start, what daunted her were the practical aspects of doing such a complex book, such as the permissions and legal aspects of using material involving third parties. That aside, how would she weave the stories about the importance of creative relationships on his literary journey into some kind of narrative arc?

Editorial and design challenges posed another hurdle. The book is bilingual and cross-cultural, with different types of content — poetry and prose by him and others, hundreds of images, plus her narrative text.

The fact that Salleh is precious to so many people who feel very strongly about how he is represented was daunting, too. Anna says: “I am quite aware that despite my connections with Malaysia, I’m still very much an outsider who has been audacious enough to write a book about Malaysia’s ‘uncrowned poet laureate’.”

Anna is grateful for support from publisher John Lee of Maya Press, designer Jun Kit, and writers Saras Manickam and Lawrence Pettener, who worked on the copy editing. Both were introduced to her by Sharon Bakar after a night at Readings in KL. She also thanks her Malaysian family, from Melaka to Selangor, Singapore and Washington, DC, for sharing their memories of Salleh.

She hopes the book will travel far and wide and serve as a starting point for curious minds who wish to explore his world view, besides giving readers a deeper insight into what made him tick.

Beyond the apocryphal tales of outlandish behaviour, what did Salleh Ben Joned really stand for? “He did not provoke without reason. He was a rebel with a cause and used his incredibly well-read mind to try and make people question perceived wisdoms that he saw as deadening to the culture and prevented Malaysia from becoming the truly inclusive nation it could be. He was, in that sense, a true patriot.”

Sieving through his personal correspondence, Anna learnt “how deeply and passionately my father felt about the world, and his place in it. Like many great people, he was full of doubt and wondered if he’d lived life as he should. Yet, he was also absolutely driven to pursue his chosen burning path”.

She is constantly mining Salleh’s archives, spread between his home in Subang Jaya, Selangor — under the care of her half-siblings Hawa and Adam [his children with third wife Halimaton Attan] and in Sydney. There are photos, personal correspondence, notebooks, articles and his unique collection of books, as well as other things he wrote, from scripts for TV3 (where he worked for a while) to essays for newspapers, journals, art catalogues, conferences and magazines.

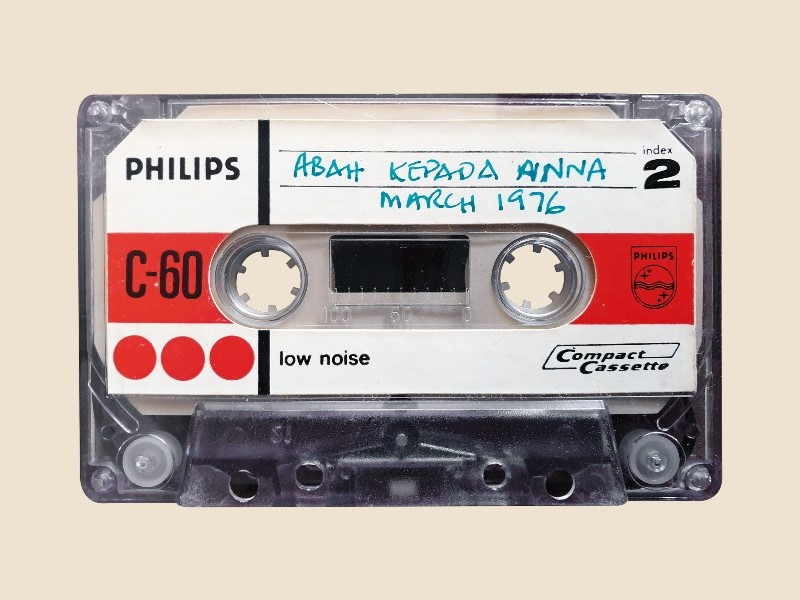

tape.jpg

Few know that before he became well-known for As I Please, his column in the New Straits Times that ran in the early 1990s, he wrote in Malay for Dewan Sastera and other Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka journals under the editorship of Usman Awang, in the 1970s.

“Salleh connected with so many groups of people, from dancers and artists to actors and poets and beyond. He was so prolific in those early days and I expect there is so much more archival material out there to be discovered, collected and published.”

If that means a project for another book, Anna, who cannot imagine life without writing, is ready. When she was eight and living in Tasmania, Salleh gave her a typewriter and she started writing an epic novel about the love letters between Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford!

“It was a kind of a fantasy that mixed up all kinds of things I was obviously hearing adults talk about around me at the time. I also still have diaries written at the age of nine describing my observations of the word. I had just come to Malaysia to live with my father, when he came back in 1973. I have always written in a journal.”

Did she ever wish Salleh was more like other fathers?

“I do remember at the age of nine, asking him to pick me up around the corner after school in Sri Petaling [in Petaling Jaya]. I didn’t want my friends to see his long hair, jeans and open-necked shirt. So, yes, like many children, I wanted to fit in.

“I could wish he was more responsible at times — he was a bit slow in enrolling me in school when we moved to Kajang. But then, those six months were when I listened to his Ella Fitzgerald and Nina Simone record collection on non-stop rotation and I’ve no doubt this was key to my musical education!

“I am not as extreme in my personality as my father, but I think we share a conviction that nothing is black and white, and the juice of life is in the grey areas.”

After Anna returned to Australia in 1976 to live with her mother, Ariel Salleh, her father would write her letters or send audio missives using cassettes. Their correspondence kept her connected to Malaysia and she would visit regularly.

c_1968_salleh_and_his_first_wife_ariel_salleh_and_daughters_anna_and_maria.jpg

“I never forgot the basic kampung Malay I learnt during my three-year stay. And it turns out those letters Abah sent me would play such a crucial role in my understanding of his inner life when it came to writing about him decades later.”

When he wrote, Salleh spoke to her as a confidant. “He told me about his work, his friends, his joys and sorrows. The letters were so very rich and often beautifully written, not only in terms of content but form. He always loved calligraphy, thanks in part to his Australian mentor James McAuley’s obsession with the art of handwriting.”

Around 2000, when medication failed to help his depression, Salleh had electroshock therapy. Did it gut her to see the chilling effect it had on his mind?

“Yes, I always describe our relationship during the last 20 years of his life as being one very long, slow goodbye as he gradually lost the ability to do what he loved — explore ideas through reading, writing and conversation. It was hard managing peoples’ expectations when they came to visit after not having seen him for a long time. Where was the Salleh they knew?

“It was hard, too, realising that, although I had interviewed him back in 2011, by the time I got serious about documenting his life and work, it was too late to ask him all the questions I had. He was alive when the podcast was made and released, and what few words he said indicated he was pleased but surprised that he was important enough to be the subject of such a project.”

Anna says she needs to recoup before thinking about her next Salleh project. What she would love to do is have his library safely curated somewhere accessible because many younger people want to read what he read.

“I’d like to get funding to digitise his personal archives; I think a more academic text about his work could be appropriate; I need to publish material that is out of print or unpublished, including his Malay writings. And, of course, there are the many letters that in their own right could, I think, make for a fascinating publication.”

What does she miss most about her father? “His smile, which was as wide as the ocean.”

Purchase Salleh Ben Joned: Truth, Beauty, Amok and Belonging (RM80) here.

This article first appeared on Dec 11, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.