Remembering 8 May 1621 (All photos: Chang Fee Ming)

Fans of Chang Fee Ming’s works invariably know that they would almost always revolve around traditional life in Malaysia, particularly his beloved home state of Terengganu, or what catches his eye whenever he wanders the planet. After all, as he is fond of saying, “To travel and see and paint is, for me, a way of learning, and part of my life’s philosophy.” Presently working on a collection of paintings from his recent travels to the eastern regions of Indonesia, he shares with us what we can expect.

Options: Tell us about this new collection of paintings that centre around Pulo Run.

Chang Fee Ming: Actually, my latest series captures my ‘snapshot’ impressions of the Indonesian archipelago — my ‘Taman Indonesia’ — similar to those miniature parks that have representative displays ... like Taman Malaysia in Ayer Keroh, Melaka, for example. I have been working on this for the last 15 years. Pulo Run — the motherland of nutmegs that were once priced higher than gold — is of course a prominent place, but not really its centre.

This group of remote islands has such an interesting history that marked the beginning of massive colonial expansion in Southeast Asia by the Dutch exactly 400 years ago, marked by the massacre of the Bandanese Orangkaya and the decimation of their people. I thought it may be meaningful to expose something related to this dark part of human history in my Taman Indonesia series so that it remains remembered.

unnamed_3.jpg

What triggered this fascination with the Spice Islands?

Honestly, I knew very little about the Spice Islands, or the Moluccas to be exact, despite travelling quite a bit around Indonesia since the 1980s. I first heard about Pulau Banda in 2004 from a director of Archive Indonesia who told me about the island when I was setting up my exhibition at the Indonesian National Art Gallery in Jakarta. She kindly invited me to stay at her house in Banda Neira as she was sure that I’d be inspired by the place. Unfortunately, I had already made plans to travel to Tibet and Qinghai for my mission to explore around the source of Mekong River.

It was only after completing that series around 2011 that I started travelling in Indonesia again, to places I had yet to discover. Although Banda never left my mind, I began with Kalimantan, and quite a few islands in Nusa Tenggara until, finally, in 2019, I decided to visit the Spice Islands. The Arab traders who had been in business with the locals there for centuries before European arrival termed it Jazirat al-Muluk — ‘the island of the kings’ — from which its Indonesian name Maluku comes.

Can you share a little more of your travel experience there?

Indonesia is a vast archipelago and the Spice Islands consist of many groups of islands, with its capital being Ambon. However, my entry into the Spice Islands was via Ternate Island in April 2019. After transiting from Jakarta, I had to catch a boat and then a car to Halmahera Island. I continued to travel to Morotai Island as I wanted to be at the northernmost tip of Indonesia where I was supposed to later get an only once-a-day flight to Ambon.

unnamed_1_copy.jpg

Upon arrival, I then planned to spend more time going to museums before catching a 12-hour Pelayaran Nasional Indonesia (Pelni) boat ride to the island I had dreamt of visiting for almost 20 years — Banda Neira! Unfortunately, the flight was cancelled due to strong smoke from a nearby volcano. Not knowing how long the weather would take to clear, I had no choice but to skip Ambon and Banda and travel all the long way back to Ternate. Tired and disappointed at not making it to Banda, I decided to return to Terengganu. That whole trip lasted about two weeks.

In December 2019, my wife Jarina and I started a trip to Maluku again and this time we decided to only focus on discovering Banda and Seram. So, from Kuala Lumpur we flew via Jakarta into Ambon. From there you could either catch an overnight Pelni or take an eight-hour fast boat (yes, a fast boat can take that long) from the ferry port just outside Ambon.

Those who are used to long-haul travel and can sleep through boat rides will do well. Others may suffer from restlessness as there is very little to do and the seascape is pretty but unvaried for hours, without a single island in sight until you hit the archipelago. So bring a good book or have a few nice movies loaded on your device. But if you’re lucky and well organised, you can also catch a half-hour six-seater flight with Susi Air, which only flies a few times a week to Banda Neira, the main island. But the flight option, only slightly more expensive than sea travel, will depend on the weather or seat availability (if the plane is not chartered).

unnamed_2.jpg

How difficult is it to get to Pulo Run then?

It is getting to Banda that is the most challenging part of the journey because once you’re on Banda Neira, its not difficult to get to Run — located at the western tip of the Banda archipelago. You can easily charter a boat from there or hop into local taxis that ply between the islands. The journey takes a bit more than an hour with a chartered boat and is simply great as the water is amazingly calm in this part of the world. Dolphins sometimes swim alongside the boat and random manta rays can be seen leaping out of the water. Turtles can be sighted from the boat too, swimming near the surface. Most visitors stay in Neira or sometimes the coral-flecked Hatta, and do day trips to Run, as the cliff-dominated island does not offer much for visitors compared with the other two.

It has been 400 years since the Dutch East India Co (VOC) enslaved and massacred the Bandanese in order to secure the spice monopoly. How does that make you feel?

As a citizen of a former British colony, there is some irony in wanting to compare with the Indonesian-Dutch colonial experience, always asking who was a better colonial ruler and such. It does seem like we Malaysians usually end up feeling ‘luckier’ or even proud that our colonial masters treated us better than the Dutch did the Indonesians. When I think of how they had used Japanese ronin as their mercenary executioners who had beheaded and quartered the bodies of the Bandanese Orangkaya, or impaled others on bamboo sticks to be publicly displayed, I understand how the Japanese army was able to impose the same cruelty to people in China and Southeast Asia during the Second World War, which was just over 70 years ago, mind you.

The fact is the VOC genocide in Indonesia was just a small part of the bloodiest expedition during the era of colonialism in the world. So, we must ask questions like what is the most important lesson we have gained from this piece of history? Are they, the former colonists, kinder now to the people they damaged in the past around the world? After ruling the world for 200 over years, they are still deploying missiles at civilian areas, causing suffering to thousands and thousands of people. In the name of army training, murder can simply be committed against innocents in Afghanistan. How is that any different from 400 years ago? But, of course, they can also claim that genocide is happening in Xinjiang now too!

unnamed.jpg

So, will the nutmeg massacre be a constant theme throughout your new artworks?

The so-called nutmeg massacre will be a small part of my work in the Taman Indonesia series, but the history of nutmeg is so fascinating. Coupled with the beauty of these almost-untouched islands, I will definitely try to catch an opportunity to return to these places. I would really like to learn more about the culture of the people there, including the ‘new’ Bandanese who replaced the indigenous people who had lived there prior to the arrival of the Dutch.

What do you feel when, in most history books, the proud, talented Bandanese are often overlooked? Most books on the Spice Islands only refer to the two great European powers — the British and the Dutch.

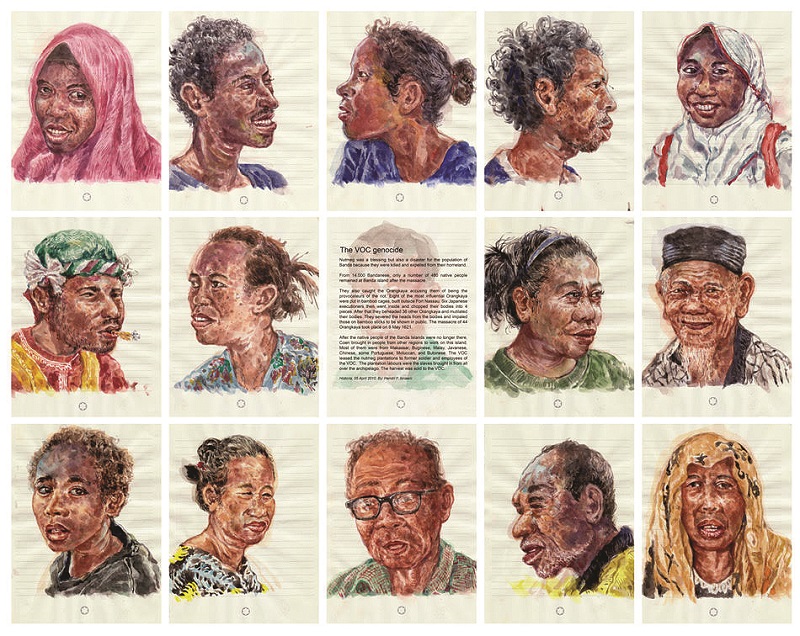

Kingmakers will write their own history! You can see how proudly the colonial powers describe their history — even a cold-blooded killer like Jan Pieterszoon Coen can be a national hero. This continues to be the case today. From what I have learnt, from originally 14,000 Bandanese, only 480 native people remained in Banda Island after the May 8, 1621 massacre. Some were then caught and sent to Jakarta as slaves. The Orangkaya, accused of being provocateurs, were beheaded and mutilated. May 8, 2021 marks the 400th anniversary of their massacre. A small group had escaped the island and managed to find refuge on a few neighbouring islands, particularly Kei.

Coen subsequently brought in people from other regions to work the land. The VOC then leased the nutmeg plantations out on the basis that all the harvest be sold back to them. Most of the present population of the Banda islands had come here from elsewhere, not only from various islands in Indonesia but also as far as China and Yemen. From this point of view, I believe that there is not much left of the original Bandanese culture. Today, it is hard to find a true native Bandanese when you walk down the main street of Banda Neira unless you’re lucky. So I hope my work on this subject will, in some small way, at least redirect the focus back to the Bandanese, past and present.

sketching_in_banda_neira.jpg

The Bandanese were outstanding traders and master navigators of their time, correct?

They were surely very sophisticated traders because, long before the Europeans found their way to the Banda archipelago, they had already traded with various people: those from the Malay archipelago, as well as Arab and Chinese traders who then introduced spice to the West. That is why they refused the proposed Dutch monopoly on nutmeg. The title of master navigators might perhaps refer more to the people of Celebes, as the Bandanese probably specialised more in tending to their precious nutmeg trees and then selling nutmegs, rather than venturing to far-off islands.

What do you want people to see or feel when they view your new Spice Island-inspired pieces?

I can’t say what I want to tell other people. As an artist, the painting process is a private moment where I relive the strong connections I felt from my travel and the sense of joy that these places gave me. I did learn a lot during the journeys I made in Banda and try to put in some of the energy and thoughts I had into the paintings and share the result with the public. Of course, if the paintings could inspire someone or make people want to visit this historical chain of islands, I would be most grateful.

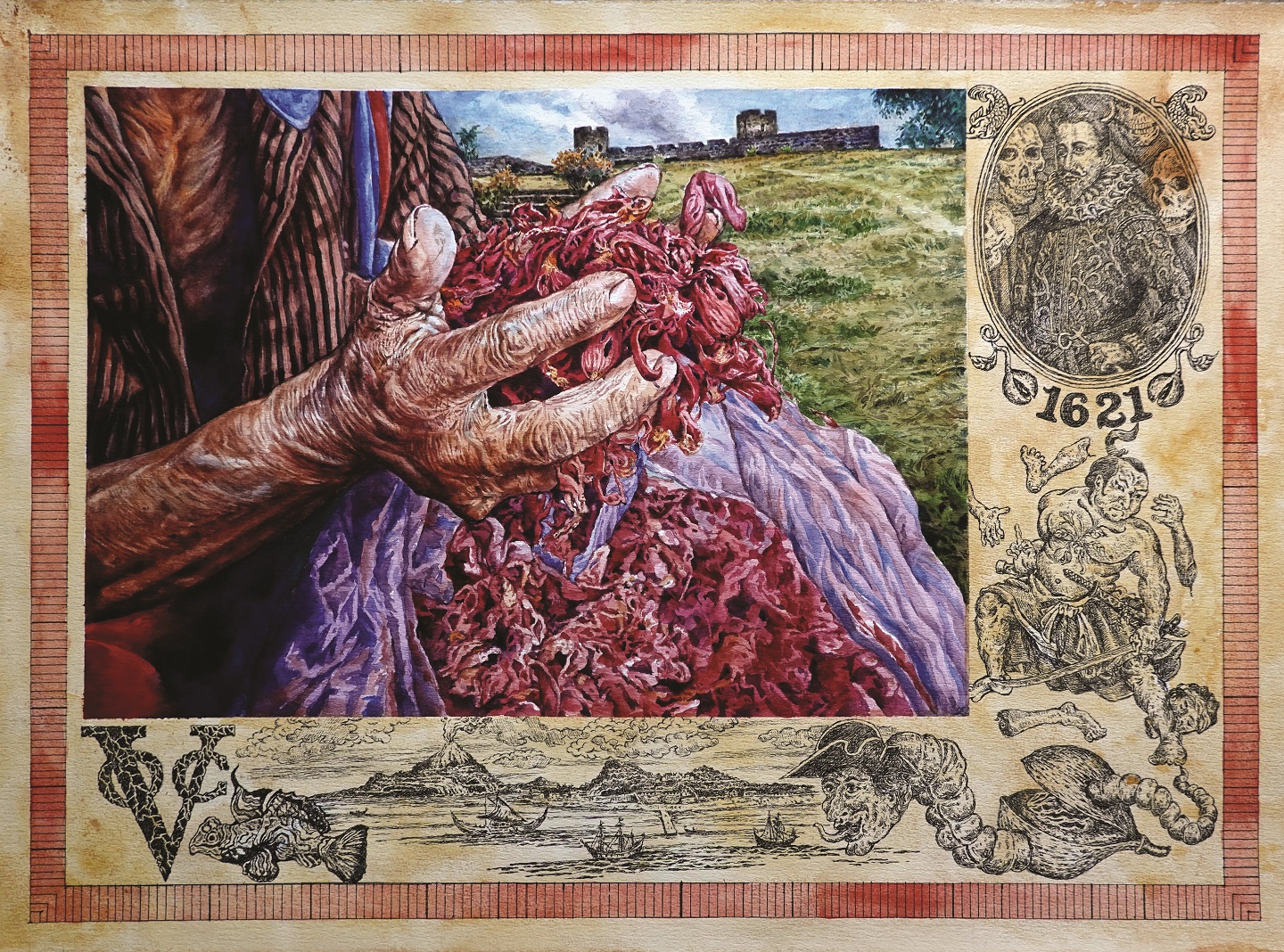

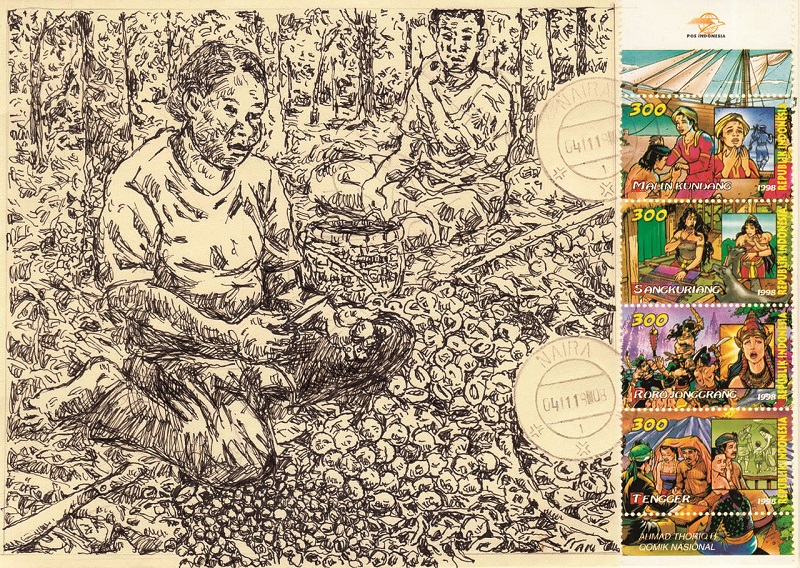

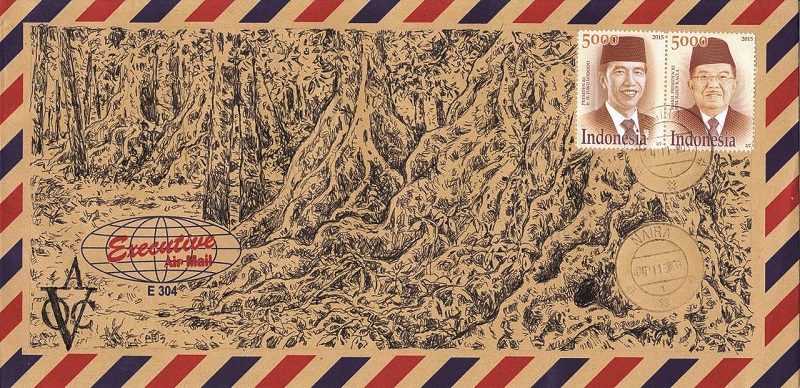

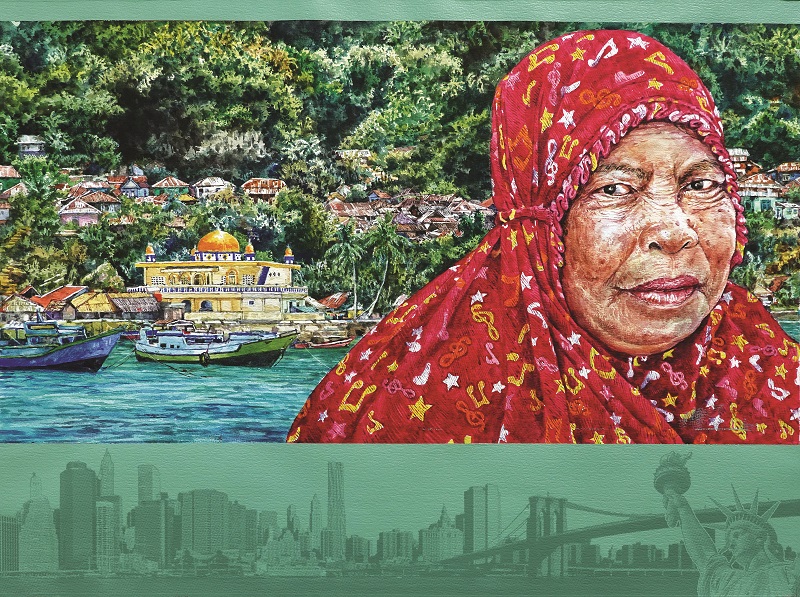

Right now, I have finished three major works on Banda. The first, Remembering 8 May 1621, features a nutmeg farmer I met near Fort Belgica and I combined some drawings created from an old illustration as the border of the painting. The Barter features a woman in Run Island today coupled with an illustration of the New York skyline, while The Descendant features a Chinese man in a 300-year-old Sun Tien Kong Temple. I combined that work with a Chinese text that I got from the Daoyi Zhilüe.

the_barter_july_31_1667.jpg

Today, we sprinkle nutmeg powder on our espresso, add it to eggnog, or mix it into the filling of a pumpkin pie. There is no doubt that most people may not be particularly curious about its origins. After all, it is found in the spice aisle of the supermarket, right? Fewer people will consider the tragic and bloody history behind the spice. Over the centuries, thousands of people have died because of nutmeg.

The reason Venice became the most powerful maritime empire in Europe was precisely because it controlled the nutmeg that Arab merchants transported to Europe. Later, the Arabs threatened to disrupt the supply of spice and nutmeg, so Venice launched the largest barbaric and most undignified plundering war in human history — the Fourth Crusade in 1204 — having recruited mercenaries from France and elsewhere and using them to attack the city and plunder ... after promising to share the spoils together, of course. The pawns always got the petty profits. I would say what was termed a Holy War was just a bid to control the most expensive commodity in the world at that time — oriental spices.

This article first appeared on May 3, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.