Jeremy "Sequoia" Nagamatsu is an American novelist and short story writer (Photo: Sequoia Nagamatsu)

Climate researcher Clara had fallen to her death at the Batagaika Crater in Siberia shortly before discovering the 30,000-year-old remains of a young girl, believed to be the victim of an ancient virus. When archaeologist Dr Cliff Mayashiro arrives at the research outpost in 2030 to help finish his daughter’s work, a quarantine had just come into effect — standard protocol, he is told — because scientists there had reactivated viruses and bacteria in the melting permafrost.

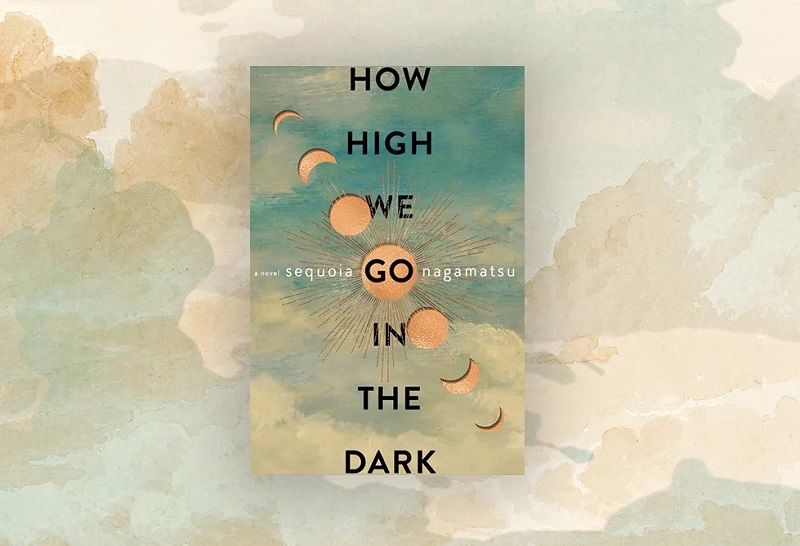

With this alarming start, How High We Go in the Dark takes readers across centuries and continents, beyond time and space, following the arc of an Arctic plague that punctures the lives of interconnected narrators.

The individual stories in Sequoia Nagamatsu’s debut novel are haunting: A scientist who could not save his own son experiments with donor pigs to produce organs for dying children; a researcher studies how patients fall apart even as doctors race to keep them alive and intact; lonely strangers meeting in virtual worlds; a costumed attendant who secures infected children on the theme park’s roller coaster for one last ride before their hearts stop; and an elegy hotel worker whose job is to cart bodies from bed to crematorium after families have curled up with the corpses of loved ones to say goodbye.

But Nagamatsu does not wallow in tragedy and loss. His characters react to the global crisis, and mend, in different ways. Community is the glue that holds them together and resilience the force that lifts their heads skywards to look for the stars. In an email interview, the Japanese-American writer tells Options about his book.

How did the idea for How High We Go in the Dark come about years ago and what prodded you to complete the manuscript in 2020?

The earliest seeds of the book began around 2008 while I was living in Japan. I had been doing a lot of research and story brainstorming revolving around alternative forms of grief and innovative funerary practices in the wake of my grandfather’s death. The increasing merging of technology and major metropolitan realities, along with tradition and spirituality, was something that fascinated me. I began asking myself: Are there better ways for us to grieve? Are there better spaces for us to enter into a dialogue with mortality when capitalism and busy urban life so often leave very little room for memory and homage?

The plague backdrop entered into the manuscript around 2014 after I read an article in The Atlantic magazine. I published a story collection [Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone] in 2016 and had been working on other unpublished manuscripts along the way. So, I wasn’t consistently working on this book as a project the entire time, although what would become the novel was simply growing and evolving, at its own pace. I was developing as a writer and living my life — getting tenure as a professor, several major moves across the country, getting married and so on.

how high.jpg

In the acknowledgments, you named books that helped you wade through the complexities of death and grief. In interviews, you mention estrangement and reconciliation with your father. Was writing this book cathartic? Did it bring you consolation or closure?

It was in a lot of ways — some of the chapters are very autobiographical (especially Elegy Hotel), and especially when I was revising this book during the pandemic: wading in a plague that was far worse than our own was oddly comforting. Being in conversation with my characters who were often wading with their own losses and own decisions about how to move forward helped me make the right decisions in my own life and find closure when my father died a little over a year ago.

Bloomsbury got your draft in April 2020 and this book was released in January. In the interim, were any parts tweaked to reflect how the coronavirus had affected the world?

I was deepening character connections between chapters, evolving the world over generations across the book in terms of the virus, climate change and technology, as well as creating hints that would help the reader appreciate the framing of the opening and final chapters. Beyond these revisions, I was also making sure to diminish any clear parallels that may have appeared in the novel by coincidence that would remind the reader too much of our own pandemic.

Additionally, I wanted to ensure that the Asian characters in my novel were existing on their own terms and never ‘othered’ for a white audience. I wanted the Asian and Asian-American characters simply to exist as victims of a tragedy like anybody else, especially given the rise of anti-Asian hate in recent years.

In light of the global pandemic, would you say your book is prescient?

It’s strange, certainly, but I resist calling anything prescient at this point since the word seems to have lost meaning. A lot of things can be seen to be prescient whether they really are or not, but I think I’m more concerned with how narratives and media are genuinely engaging in a dialogue with how we are living and how our culture moves beyond this moment.

If my novel had been published in 2020 instead of 2022, I imagine the reaction would have been very different (and many may have resisted reading it despite the fact that it’s not really a pandemic novel with a capital ‘P’. In other words, it’s not a novel about a virus so much as community, connections, grief and resilience).

Entering into the third year of the Covid crisis, I think more people are willing to engage with what it means to be living in this moment, how we’ve already changed, and how we can use this moment to reimagine better versions of ourselves and society.

You and your wife (writer Cole Nagamatsu) founded Psychopomp Magazine to publish fiction that redefines traditional storytelling and genre borders. Why do speculative fiction, the supernatural and parallel realities appeal to you? Is that what new and younger writers and readers are exploring today?

We started the online journal in 2013 as we saw a need for more publications to support emerging writers who write innovative prose. The landscape has changed dramatically since, but at the time, there weren’t many publications open to newer writers who blurred genre and form.

For me, speculative and fantastical fiction appeals because these narratives serve as an exciting/eye-catching lens through which to unpack human behaviour and society from outside our everyday worldview.

I also think science fiction in particular is increasingly becoming a default mode for many writers (even those who might consider themselves realists), seeing that the gap between ‘our reality’ and what one might consider ‘the future’ is ever shrinking. We are living in the future. We are living in a dystopia. We are living in a climate crisis. In a lot of ways, conventional realism fails to address these conditions in a way they deserve to be explored.

As a child who read, did writing come naturally to you? Does teaching creative writing (at St Olaf University, Minnesota) bring something to it? You struggled and ‘floundered’ too. What kept you going?

I was always a bookish child. I read a lot and liked telling stories. But, like most people, pursuing the arts seriously isn’t something that comes naturally because our parents or society tells you that isn’t realistic and you should pursue careers that might be more financially stable. But I kept coming back to the writing and eventually returned to graduate school to pursue it seriously.

I was honestly just lucky (and certainly worked hard) to get where I am now as a tenured creative writing professor — a lot of talented writers want these positions but aren’t able to get them. I don’t know any writer who doesn’t struggle or flounder. It’s just part of the process, part of the life. But I keep going because it’s something I ultimately love doing.

Every story in How High We Go in the Dark leads back to the Arctic plague, and characters from the earlier pages have a link, directly or indirectly, to subsequent stories. What are you trying to tell readers?

The connectivity between all of us in time and space in big ways and small, the focus on community and relationships in helping us emerge out of dark times, but, of course, the ripple of tragedy is also there. All of those things are present. You can’t really have one without the other.

People escaping to virtual worlds, funerary skyscrapers, grave friends, robot dogs and a talking pig reared for science — how did you come up with these ideas? Despite all the sadness, would you say this novel is about hope and healing?

Well, I come [up with] story ideas from many, many different sources but oftentimes the seed is a merging between a character I have in mind, alongside real world research — a new article, an experimental technology or theory, or a collage of my own experiences transplanted on a near future landscape. And while there is a lot of loss and death in this novel, that was never the point. It’s a book about hope and healing and connections. But to experience and portray this I, of course, need to create a loss from which our characters can venture forth.

Do you have a routine when writing?

This really depends on the time of year. Being a professor is a huge time commitment (and I also often have other demands on my time beyond my primary job). But I try to write, or at least think deeply about my writing, for an hour every morning. When I’m on a deadline, I try to carve out three to four hours a day, which is about my time limit before my creative brain ceases to be efficient. That said, there were moments when writing How High We Go in the Dark [that] I wrote for 12 hours a day for multiple days in a row. It isn’t my normal routine, but sometimes this is just part of the process when you work with a publisher.

What are you reading now and which writers have influenced you? Are you working on any new books?

I’m reading the Children of Time series by Adrian Tchaikovsky, Out There by Kate Folk and The Cat Who Saved Books by Sosuke Natsukawa. As for writers who have influenced me: Italo Calvino, David Mitchell, Haruki Murakami, Yoko Ogawa, Kevin Brockmeier, George Saunders and Kelly Link. I’m currently working on a second novel for William Morrow and Bloomsbury called Girl Zero.

This article first appeared on Mar 21, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.