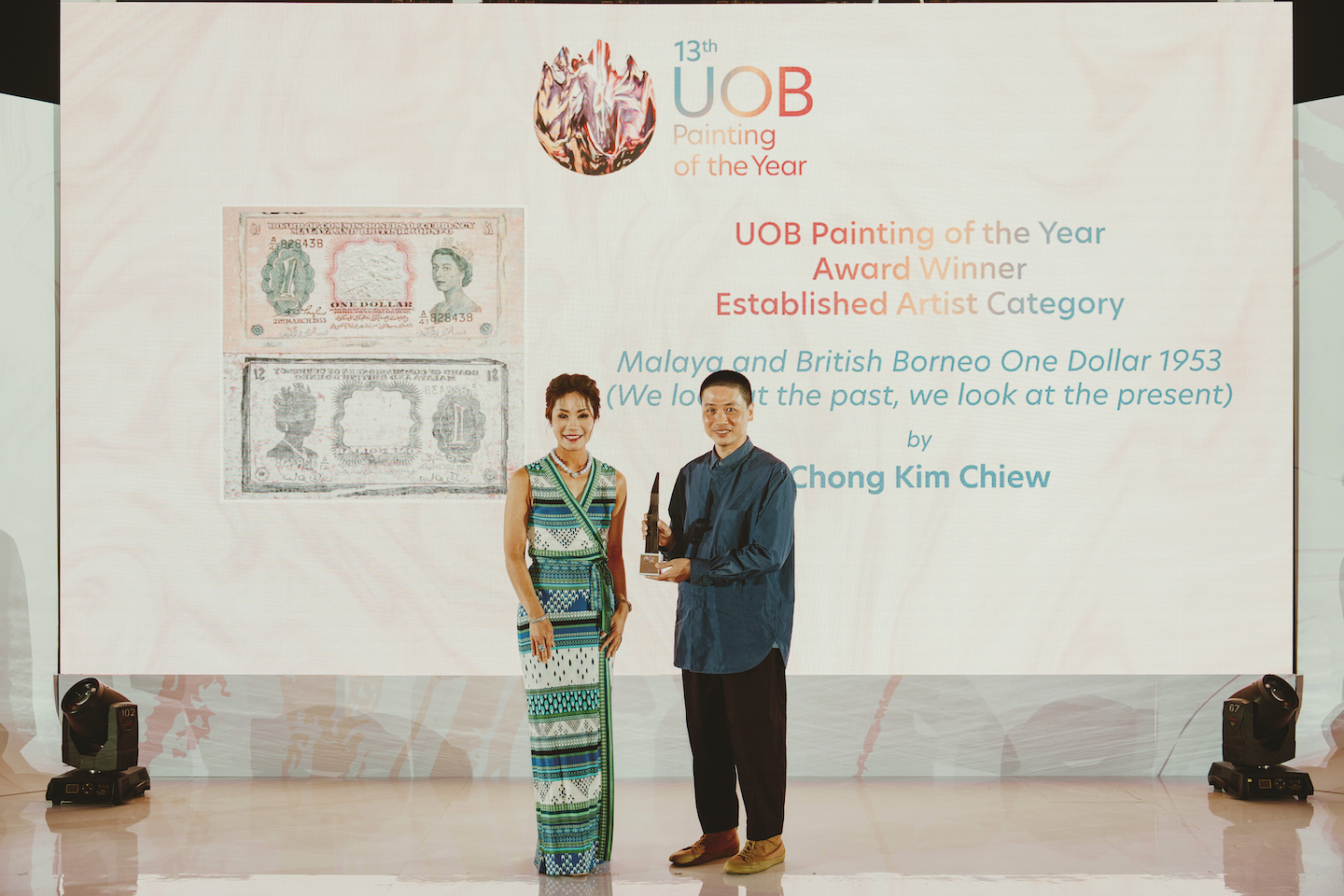

Chong Kim Chiew with Ng Wei Wei, CEO of UOB Malaysia (All photos: UOB Malaysia)

Encounters with foreigners who showed no interest in Malaysia sparked the idea of “using our stories and memories” to tell the country’s narrative. As Chong Kim Chiew explored how the past shapes the present, he was drawn to the relationship between art and money, and the fluctuating value of artists and their works over time.

Chong’s Malaya and British Borneo One Dollar 1953 (We look at the past, we look at the present) won the RM100,000 top prize for the 2023 UOB Painting of the Year Malaysia (Established Artist Category). He will compete with winners from Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam for the UOB Southeast Asian POY award, to be announced on Nov 8 in Singapore, which comes with an additional RM13,000 and a month-long residency programme at the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum in Japan.

The gold, silver and bronze recipients of the 13th edition of this competition are Hasanul Isyraf Idris (How to Disappear Under the Brightest Star), Nik Ashri Nik Harun (In the Quiet Whiteness, The Darkened Silence Resonates) and Umibaizurah Mahir Ismail (Uncharted Realm) respectively. Yap Chee Keng’s Broken Screens and Freedom Struggles was highly commended.

In the Emerging Artist Category, Mairul Nisa Malek was chosen Most Promising Artist of the Year for Malek and Mariana, a mixed-media creation named after her parents. Ahmad Syakir Hashim (For the Love of Sweet and Bitter Truth), Ooi Yong Hui (Scars of Love, Stain of Time II) and Izhar Yusrin Zainuddin (Escape from the Plot) won gold, silver and bronze, respectively, while Not for Sale by Noor Zahran Khizan was highly commended.

2._hasanul_gold_award_1.jpg

Love for art led Chong to quit teaching the subject to focus on honing his craft. The 48-year-old graduate from the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Art held six solos between 2005 and 2021, and has exhibited at the Busan Biennale (2022), the 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (2021) in Australia and Open Sea in the Museum of Contemporary Art, Lyon (2015).

His winning work, created using acrylic, aluminium foil, lime plaster and paper with print, has two identical banknotes that give voice to Malaysia’s story. The one dollar issued on March 21, 1953, was in circulation across Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak, North Borneo, Brunei and the Riau archipelago until 1967.

The upper note, representing the country’s past and its historic context, has a wrinkled foil between the numeral one and a portrait of Elizabeth II, who ascended the throne in February 1952, creating a mirror surface that reflects the viewer’s silhouette. The lower note is mirror-reversed, allowing viewers to align themselves with the portrait as they gaze on the present through the lens of history and think about how Malaysia has changed.

“I had the idea for my banknote series 20 years ago and used the ringgit for my paintings. It wasn’t perfect, so I put that aside,” says Chong. He picked it up again in 2019 using new materials and had a solo show two years later with 20 pieces featuring the Malaysian currency and banknotes issued by the British government. “I’ve done the Japanese ‘banana’ notes too. The idea is to use them to rethink our history and how it has shaped our future.”

Each banknote has its own story and old ones fetching far more than what they are worth makes him wonder: Who determines the price of art? Would an artist’s work appreciate in value long after he is gone? “To me, this playfully challenges an artist’s pursuit of commercial value in the art world.”

Academician and contemporary artist Bibi Chew, chief judge of the 2023 UOB POY, lauds Chong for looking at the past and present from different perspectives and the multiple meanings enfolded within the peeling layers of paint in his piece. “Whatever we have now — the economy, the money we use, the value of currency and depreciation, the values we hold — is derived from the past.”

1._mairu_nisa_most_promising_artist.jpg

Choy Chun Wei and Ahmad Fuad Osman were also on the panel. The first question Chew always asks when judging an artwork is whether it engages her. Other considerations are its elements, composition, arrangement and rationale. “An idea can be executed simply and still stand out if its meaning is good. My belief is that art is meant to be shared, and I have been deeply moved by the stories told by each artist through their works,” she says.

Mairul’s story is personal, yet familiar to those who undertake tedious journeys into the interiors of Sarawak. Malek and Mariana is an eye-opening combination of cement, washed cyanotype, film, wire mesh, words and acrylic containers framed in a wooden box. It offers glimpses of life in Kabong, Betong and Kapit (where her teacher father served two decades ago).

Getting to the nearest town from these remote areas, which had no electricity until 2013 and still no piped water today, where the rare villager who builds a cement house is considered an orang kaya, can take four hours by perahu, two by bus and another hour by express boat. Pregnant women heading for the hospital have ended up delivering their babies on the boat, as happened during a trip Mairul took when she was about five.

During another ride, she observed her parents’ “devotion and unwavering sense of responsibility”. These core memories and the hardships her father encountered “inspire me to be a better person”.

Her Sarawakian upbringing kept her grounded and brought solace when she was exposed to privilege, accessibility and city life in Selangor, where she is majoring in sculpture at Universiti Teknologi Mara. The UOB POY is Mairul’s first competition. “It was only after I grew older and embraced my background — who I am, where I come from, what I have been through — that I gained the confidence to take part,” says this artist who experiments with different disciplines and plans to do her PhD after her master’s next year.

She hopes to continue her work on reinterpreting contemporary art and identity research to address artistic manifestation.

This article first appeared on Oct 2, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.