Cheong LaiTong's Image Of Rhythm

Nationhood and its various themes have been at the forefront of the art community, particularly last year, perhaps in the light of the 60th anniversary of Merdeka.

Most visibly so is The Unreal Deal exhibition at the Bank Negara Malaysia Museum and Art Gallery, which covers six decades of Malaysian abstract art. Coincidentally, the latest exhibition at Ilham Gallery has a similar theme, except that its focus is more microscopic as it reflects the wider context of our nation’s development.

In 1967, seven Malaysian artists — newly returned from their studies in various foreign countries — decided to hold an exhibition entitled GRUP. An acronym in Bahasa Malaysia for gerak (movement), rupa (form), ubur (torch) and penyataan (statement), the title functioned as a manifesto of their ambition to bring a new modern aesthetic to their art.

The exhibition lived up to the bold determination of the seven — Ibrahim Hussein, Syed Ahmad Jamal, Latiff

Mohidin, Yeoh Jin Leng, Jolly Koh, Anthony Lau and Cheong Laitong — to achieve something in the art world. To this day, this iconic exhibition is a reference point for, and an important contribution to, the narrative of Malaysian art.

“All of them are recognised today as Malaysia’s modern masters,” says Ilham Gallery director Rahel Joseph. “This year is the 50th anniversary of GRUP, and we wanted to contextualise the landmark exhibition by examining the larger story of the 1960s, which was a very important period for Malaysian art.”

In GRUP 1957-1973, the gallery chose to focus on more than 80 works by the seven artists between those years, arranged loosely in chronological order. Only one of the artworks is from the original exhibition.

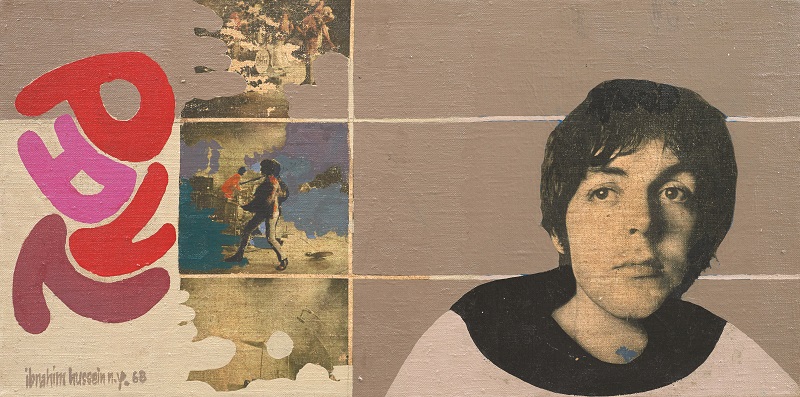

Setting the tone of the era is the opening work near the entrance, featuring one of the most famous faces of the time — Sir Paul McCartney. Simply titled Paul (1968), the atypical piece by Ibrahim Hussein captures the Beatles mania and pop culture phenomenon that the artist experienced during his stay in New York.

Indirectly, the piece also highlights the fact that the work of the seven was not confined to the Malaysian context, that their travels and exposure formed a central part of their artistic career and was a contributing factor to the burgeoning of modern art in the country.

“You can’t have a modern art movement without an arts infrastructure. So we wanted to look at the development of KL as well as the growth of the arts infrastructure in the city that cemented modern art’s place in Malaysian art history,” says Rahel.

While a black-and-white documentary on Kuala Lumpur sets the mood, the more significant highlight is a map that plots all the geographical hot spots for art and architectural development over two decades. We learn that the National Art Gallery was set up in 1958; the SAMAT Gallery was located in the Straits Building; the famed Wednesday Art Group would meet at the Selangor Education Office; and the British Council office was where exhibitions were regularly held.

We also learn how the development of the local art scene correlates with the integral roles each of the seven artists played. Most of them were art teachers in schools and later on in national institutions where they would set up or head the art curriculum that benefited a whole generation of artists who came after them.

They may have been nurturing as teachers but as artists, they were perhaps rebels, and certainly pioneers, which becomes clear when one explores the artworks with a conscious appreciation of the fact that abstract art was a new visual language at the time, particularly for audiences who were accustomed to realism and figurative works.

Take Koh’s Road To Subang II (1969) and Two From Alor Setar (1969). The titles were meant to depict a particular scene but what is seen are in fact blocks of colour. The viewer is invited to imaginatively draw his own images from the masterful use of colours, which evocatively conveys the scenes Koh had seen. Timang (1964) by Syed Ahmad Jamal is similarly expressive.

Even Yeoh’s Seberang Takir (1964), which is arguably the most realistic, has enough abstract quality for us to fill in the blanks visually. Experimentation with traditional forms is also evident, notably in Syed Ahmad’s Jawi script-inspired Tulisan (1961) and a few of Cheong Laitong’s works with their Chinese calligraphy element.

A large presence in the exhibition is Latiff’s well-known series, Pago-Pago — a name coined from “pagoda” and “pagar” (fence). In it, the artist combines geometric, ethnic and other elements inspired by his time in Berlin and his travels around Southeast Asia.

What is conspicuously absent is a strong political tone. Rahel observes that this perhaps had to do with the era our nation was in then. “Being part of a time when so much was happening in the country, I think the optimism, hope and concerns then nonetheless come through in their works, [although] they might not be responding specifically to the political developments of the time,” she says.

Cheong’s Malaysia Merdeka (1962) embodies this in broad, energetic strokes that evoke a sense of joy, community and, as curator Simon Soon suggests, sound waves.

Highlighting the impact of the seven on our art scene, Rahel says, “They came back from their studies abroad, bringing with them the tenets of modern art that they had absorbed. They rejected the previous generation of artists with their naturalistic depictions of the physical world. They also had an internationalist sensibility. They carried themselves with confidence, saw themselves as professional artists. Some of them also contributed a great deal to art education in the country. Syed Ahmad Jamal also served as the National Art Gallery director from 1983 to 1991.”

GRUP 1957-1973 is on view at Ilham Gallery, Menara Ilham 8, Persiaran KLCC, KL, until Feb 25. For more details, visit www.ilhamgallery.com.