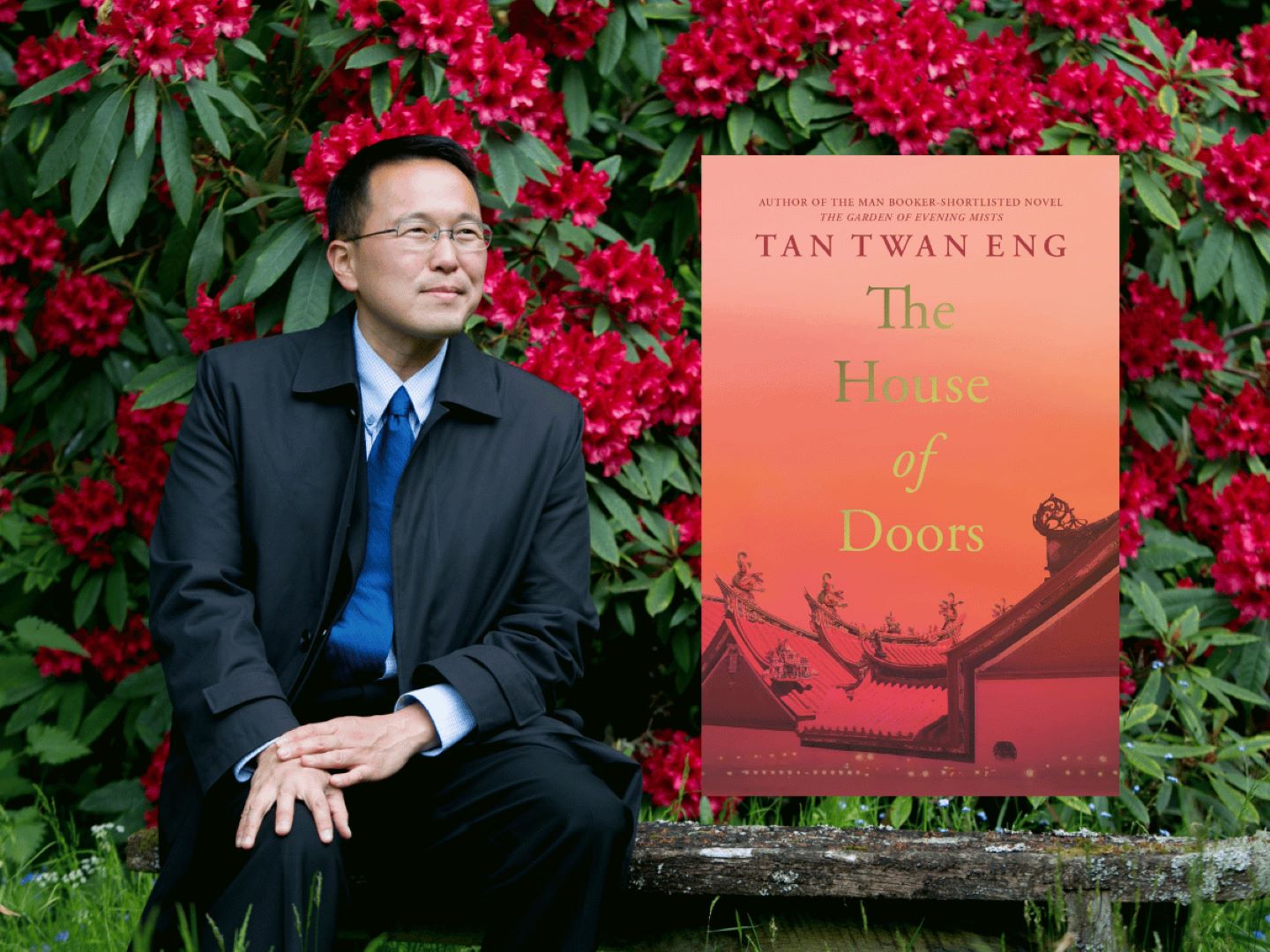

The House of Doors is a quiet invitation into a book that whisks the reader from Penang (Photo: Canongate Books)

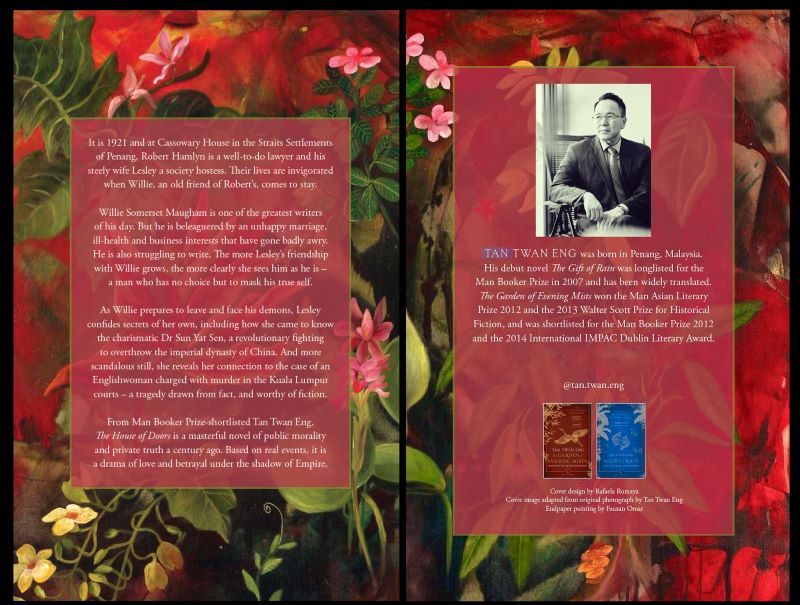

Time and place come across stronger in Tan Twan Eng’s The House of Doors than a cast of characters caught up in the languid routine of life in colonial Malaya, often portrayed by British authors, among them William Somerset Maugham, in books set in those days. Real people and events figure in Tan’s third novel, which is published a decade after his Booker-shortlisted The Garden of Evening Mists (2012).

Willie Somerset Maugham, a college friend of lawyer Robert Hamlyn, comes to visit him and his wife Lesley at Cassowary House in Penang, with his secretary Gerald in tow. The famed writer is in poor health, unhappily married to Syrie and has just learnt that a bad investment has wiped out his wealth. It does not take long for society hostess Lesley, herself increasingly distant from Robert — he has changed after returning from the war — and grappling with emotions she has to stifle, to realise Willie and Gerald’s covert relationship. Over the course of two weeks, she and Willie connect, and she starts to confide in him, sharing her own secrets and those told to her by others, knowing they could end up in a book. “He pans anecdotes and sketches for nuggets that could be smelted and hammered into stories.” But the urge to tell somebody is like an itch that cannot be ignored.

Thus begins a series of stories that unfold back and forth between 1921 and 1910, a period Tan captures in vivid detail, especially the changing hues of the tropical landscape; the culture and behaviours Willie absorbs and stores away; and imposing mansions where masters and memsahibs command a host of the local help — all-too-familiar characters who hold no surprises — and throw regular parties at which gossip is lapped up with the same relish as the liquor. Beneath the bonhomie and marital contentment lie discontent, pretence, adultery, betrayal and, always, the fear of being found out. After all, “no blade is as sharp as a man’s tongue”.

house_of_doors.jpg

Public morality holds up the structure of society and silence women who would rather risk a death sentence — as faced by Lesley’s old friend Ethel Proudlock, charged with murdering William Steward, whom she claims attempted rape — than be called a harlot. Tan dips into this historic trial that scandalised British society in Malaya in 1911 to nail that point.

He anchors this story of love and longing with observations on the politics of the day and the social mores of the period it is set in. History, personified by Dr Sun Yat Sen, the revolutionary working to overthrow the Qing Dynasty and create the People’s Republic of China, steels the framework of The House of Doors. As happened in real life, Sun visits Penang to rally support and gather funds. Lesley is drawn to what he represents, leading Robert to think she is attracted to the rebel. Steathily, she hides her feelings for Arthur Loh, a young doctor working for Sun’s cause. He leads her to the house left to him by his beloved grandmother, inside which hang many doors.

Suspicions of who is bedding who among the albeit fictional upper-crust British society and dangerous liaisons that could lead to a course of no return for the colonial wife, if caught, do little for the reader here because they seem stuck in an era that we have moved on from. Love found, lost or unfulfilled, confessions forced or spilled willingly, and privileged people hit by hard luck leave us untouched because they do not go deep enough to cause the outsider pain. Lesley’s meetings with Ethel in prison and the scene of her being whisked away to jail only arouse cursory curiosity in the reader, who is like a bystander watching the turn of events.

Alternating chapters, told by Lesley and about Willie, have the same tone and a listless quality that hardly draws us in, the way confessions and admissions do, perhaps because there is little that is new in this book, even revelations wrapped around homosexuality, an unspeakable horror at the time.

talk.jpg

The House of Doors is a quiet invitation into a book that whisks the reader from Penang, which drips with old-world charm and vibrant culture, to a vast, bleak countryside in South Africa where the Hamlyns move to because it is good for Robert’s lungs. There is a genteel quality in the writing that sits well with the slow telling of what happened to whom.

Tan, who divides his time between Kuala Lumpur and Cape Town, is at home in both settings and it shows in his atmospheric descriptions of places, especially those where Lesley finds joy. He is a sharp observer who stitches bits and pieces together to map a life, a lifetime.

But a reader who steps through the doors of this house hoping to be surprised may be disappointed to find tales as old as time, told in a way that leaves her wanting more.

Purchase a copy at Lit Books or GerakBudaya Penang.

This article first appeared on May 15, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.