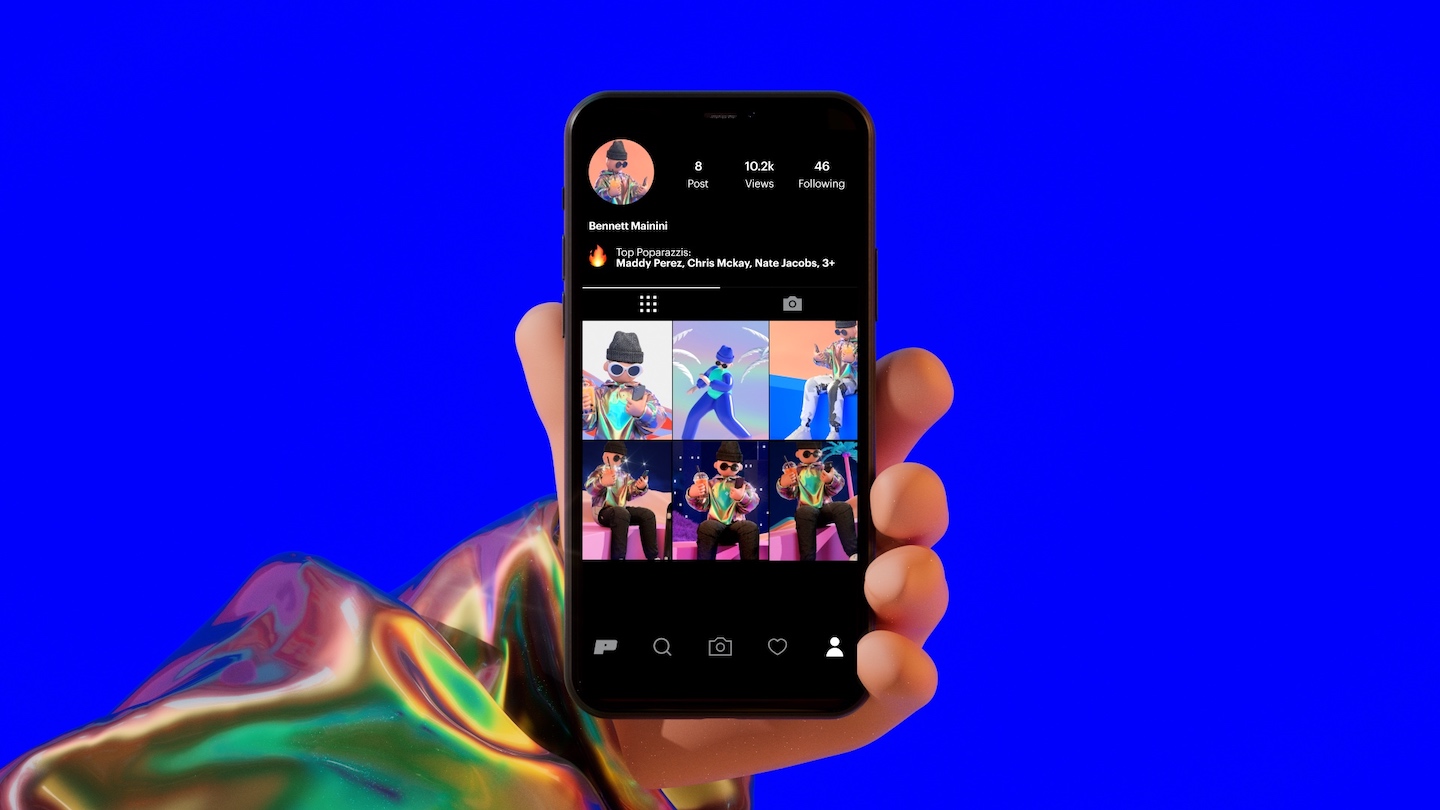

Poparazzi is a photo sharing app where users' social profiles are created by their friends (Photo: Poparazi)

Like fast food, social media is designed to lure us into gluttony. Nothing fires up our brain’s reward circuitry as satisfyingly as an infinite scroll of food pictures and celebrity posts preaching positivity. In the same way McDonald’s hypes up its BTS meal by dressing up regular McNuggets with new dipping sauces, social media keeps us hooked by constantly rolling out digital upgrades such as photo apps with augmented reality filters or nifty video editors to create montages of our dancing cat.

Tech companies are ruled by a profit model that captures our eyeballs and triggers our insatiable checking for likes and approvals that make us hungry for validation. Current photo apps have set off a trend of perpetuating unattainable lifestyle and beauty standards that have engendered social media envy. But brothers Alex and Austen Ma, who graduated from UCLA and founded audio-based social network TTYL, were not lovin’ it.

Tired of colour-corrected aesthetics and living in influencer overload, the pair created photo-sharing app Poparazzi, which has ranked No 1 on the App Store in the US since it debuted a few weeks ago. Billed as an “anti-selfie” app, Poparazzi has an unusual premise that is driving the intrigue: Your user profile will be moulded by friends. Since the app’s camera function cannot be flipped to be front-facing, you will populate your feed with pictures of other people and shots of yourself that others have taken or uploaded. All that is left to do is just “get ready for those flashing lights”, as Lady Gaga advises in her hit song Paparazzi.

austen_left_and_alex_ma_founders_of_new_photo-app_poparazzi_photo-_daniel_nguyen_photography_ttyl_.jpeg

Unlike the actual cat-and-mouse trade of celebrity chasing and stalking, Poparazzi users will remain in control of their photos, allowing only approved followers to post directly to their profile. They are also given a “pop score” based on the photos they take or upload to the app. Follower counts are not displayed on user profiles and photos cannot be commented on or liked, but can be reacted to with emojis.

These off-the-cuff approaches probably fit in with modern users who gravitate towards a progressive generation that tears down racial walls, smashes binaries and appears more “real” on social media. Poparazzi was created to depressurise the social media environment and encourage content that is less rehearsed and manicured than what is typically found on platforms such as Instagram, which has metamorphosed into a tangle of social networks where photos wrestle with Stories, IGTV and video clips for attention.

Explaining the idea behind the app, the founders said in their launch-day statement, “We built Poparazzi to take away the pressure to be perfect. We did this by not allowing you to post photos of yourself, putting the emphasis where it should’ve been all along: on the people you’re with. On Poparazzi, you are your friend’s paparazzi, and they are yours.”

Poparazzi’s launch could not have been timelier as most countries are experiencing #HotVaxSummer, a trending phrase that has become part of the online vernacular that sums up excitement for everything from the routine to the risqué, post-vaccination. Whether it is a bar meet with friends or a couple’s rendezvous, people are trying to manifest a summer 2021 that will more than make up for the abstinence of 2020. This also means that more inoculated people will emerge from their quarantine bubble and get back on the streets — an opportune time for more social media activities.

poparazzi.jpeg

Initial reactions to Poparazzi were swift. The founders claimed more than one million photos had been shared and they were set to raise funding from venture capitalists that would value the buzzy app at as much as US$135 million. But is this bona fide challenger to existing photo-apps truly an altruistic act of defying the pursuit of perfectionism or just another repackaged social media vehicle to fuel our internet addiction?

If our Instagram identity is an idealised persona we have meticulously cultivated, who is to stop someone from directing the way a friend takes a polished Poparazzi shot of ourselves before the photo is uploaded? Poparazzi has removed the “like” button, making a case for real-life connections through “reactions”. But wouldn’t these reactions, as well as view counts, also contribute to the same pressurised environment that the app founders seek to eliminate in the first place?

The current narrative of our online moment concerns the decline of text and the exploding stream of audio and video, which particularly appeals to pre-teens who have never known life without connectivity. Capitalising on their ever-growing digital interest, Facebook has been working on a child-friendly version of Instagram since March, so children below 13 can use the photo-sharing app legally. Called Instagram Kids, the (seemingly) ad-free app is said to “deliver experiences that give parents visibility and control over what their kids are doing”.

Altruistic? Maybe not, if you have examined how most Facebook features, including its first foray into children’s content named Messenger Kids, are gateway products to get more people onto their platform. A child’s version of a pervasive app like Instagram, which could expose the vulnerable to online predators and cyberbullying, does not fill a need beyond Facebook’s commercial ambitions. Safe haven or not, this is an app that no one asked for.

mark.jpeg

Our reality has always been mediated and documented. Perhaps, we should not ask whether social media is good for us but rather, how it can be used for good. On a positive note, newer digital products are moving away from overly curated content as celebrities and influencers are actively speaking out about the stress that comes with maintaining perfection. Even the public has become more aware of the prevalence of sponsored posts or that candytopia visual feed that has been played out too many times.

To be fair, peer-to-peer connectivity such as photo apps are more than just confessional booths or swipe-to-refresh slot machines that slake our thirst for stimulation. Whether jam-packed with smart commentary or humour, they have given the minority a voice and the world a free space for discourse, as well as memes that sometimes have more sticking power than arguments.

But we have already been warned. A steady diet of fast food, be it for our brain or our gut, is never beneficial to our well-being. Social media, before the exploit of algorithms and monetised opportunities, was built for fun anyway. So, maybe, cut down on the #Reels and #KeepItReal.

This article first appeared on June 7, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.