The old gleam of the City of Light illuminates the Games (Photo: Paris 2024)

If the ancient Greeks gave us the Olympics, it was a 19th century French aristocrat who re-lit the flame — after a timeout of 1,503 years. The inaugural “modern” Games was staged in Athens in 1896, but Baron Pierre de Coubertin was the driving force behind the resurrection. He not only ensured that Paris had the honour in 1900 and again in 1924, but that even a century after it last played host, the Olympics has not lost its French accent.

Along with English, French is one of the two official languages, and France is second only to the US in hosting the most Olympiads (Winter and Summer) with five. Whether on the banks of the Seine or on the slopes of the Alps, there was always a whiff of garlic. The cock-ups were dismissed with a Gallic shrug while the idiosyncrasies invoked a certain je ne sais quoi.

Proud of its role in this sporting renaissance, France is hoping that over the next three weeks, a few more historic firsts will provide a feel-good distraction in these uncertain times. One thing is for sure: It will make more impact than the first time it played host in 1900 when many competitors — including champions — were unaware they were Olympians!

Following the Greek tradition, the Games were combined with cultural events such as art and music, but even an eclectic mix of sports from croquet to motor racing was no more than a sideshow to the World Fair. Dubbed “International Contests of Physical Exercise and Sport”, they lacked the authentic Olympic ring, not helped by the absence of ceremonies and a six months’ duration.

Still, despite the branding issue, the first Olympics in France made history with several momentous breakthroughs. Almost 1,000 athletes took part, including the first women and the first Asians.

Cricket, rugby, golf, tug o’ war and Basque pelota also made fleeting appearances while core events like swimming and athletics would be unrecognisable today even if they guaranteed an audience. In the obstacle race, swimmers had to clamber over boats while the long and high jumps were performed on horseback!

Tennis provided a touch of class with reigning Wimbledon women’s singles queen Charlotte Cooper becoming its first champion. But golf went incognito with Chicago student Margaret Ives Abbot winning a nine-hole event and going to her grave in 1955 unaware she was America’s first female Olympic champion.

Similarly unsung was rugby’s Franco-Haitian centre Constantin Henrique, who became the first black gold medallist. The first Asian athletes to take part were Firidun Malkom of Iran and Norman Pritchard who, despite his Anglo name, won silver in the men’s 200m and 200m hurdles for India, the country of his birth. He would go on to make a bigger name in Hollywood long before anyone thought of Bollywood.

2024-07-10t110812z_286227098_mt1brgimg1708461_rtrmadp_3_bridgeman-images.jpg

Swimming was held in the Seine where fast times might have aroused suspicion but the “performance enhancer” was the favourable current. Another curiosity was that instead of a medal, one of the prizes was a 50-pound (22.7kg) bronze statue of a horse.

In many events, clubs took part rather than countries, teams were often of mixed nationalities and crowds were poor: only 500 spectators watched the football final while at croquet, there was just one.

Athletics was held not on a track but a field of soft grass that cut up when wet, hurdles were made from broken telegraph poles and shooting had live pigeons as targets — just one of the many ancestral no-noes that are hard to get our 21st century heads around.

Indeed, De Coubertin himself was a controversial figure. Forward-thinking on the one hand, nationalist, racist and misogynist on the other. Critics accused him of wanting to boost sport in schools and maintain French as a prominent language after defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. Resurrecting the Olympics, he thought, would help towards both goals.

But he also said: “An Olympiad with females would be impractical, unappealing, uninteresting, unaesthetic and improper”, while even the Olympic motto, “Citius, Altius, Fortius” (“Faster, Higher, Stronger”) was borrowed from Father Henri Dido, a prominent Dominican cleric.

The sports themselves didn’t take place without controversy. It is claimed the first three finishers in the marathon took a shortcut while in rowing, several ultra-light coxswains were actually local schoolboys under the age of 10.

Just 24 years and a world war later, the Olympics were back in Paris and French influence was at its height: It also hosted the inaugural Winter Games in Chamonix in the Alpine south. By now the Games was getting its act together after a few ropey years before World War I and was earthing the superstars by which each edition would be remembered.

Anyone who has seen Chariots of Fire will get more of a feel for these Games where the real-life battles of British sprinters Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell would become immortalised in the Oscar-winning movie. Liddell, a Scottish missionary’s son born in China, famously refused to race on a Sunday so he had to switch from his favourite 400m to the 200m, but still won gold. Abrahams, fighting antisemitism, won the 100m.

Future silver screen stars Sonia Hene, who skated for Norway in the Winter Games at 11, and US swimmer Johnny Weissmuller, who starred with three golds plus a bronze in water polo, first came to world attention. Both would go on to become movie stars, with Weissmuller immortalised as Tarzan.

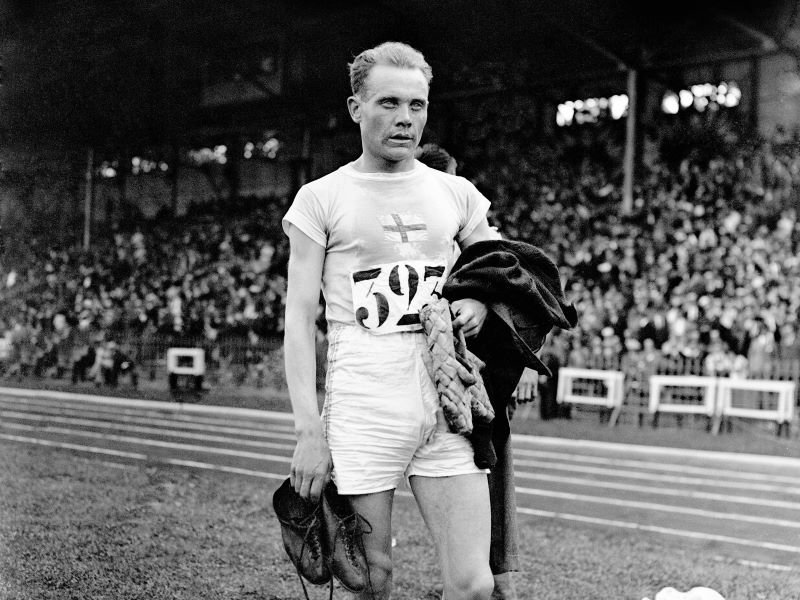

He might have played one of the great fictional characters of the 20th century, but his five Olympic golds were still no match for the immortal Paavo Nurmi with nine golds and three silvers. It was the era of the “Flying Finns” and Nurmi flew highest. Denied the chance to defend his 10,000m crown by his own association, that thought he was racing too much, he gave the perfect riposte by winning both the 1,500m and 5,000m even though there was only an hour between the two races.

1924-07-11t000000z_1625262777_mt1pra5362131_rtrmadp_3_pa-images.jpg

By now, the Games was being properly referred to as “the Olympics” and gathering interest in the host city and beyond. Numbers were up: 44 countries sent a total of 3,089 athletes to take part. The motto was used for the first time and thanks to the likes of Weissmuller and Nurmi, it did not seem out of place.

There was still a cultural event that went alongside and it still lasted an age — from early May to late July — but there was no doubt that sport was now in the ascendancy. And at the Winter Olympics, held at the foot of its highest mountain, Mont Blanc, France played the perfect host. All the gold medals were won by the guests and that, too, was a successful event. In winter and summer, 1924 was a turning point.

Thanks to the upheaval of WWII and the wider spread of the hosting duties, it was 1968 before France had the honour again. It was another very different world: both West and East Germany took part and there was also drug and gender testing. But France made up for its gold abstinence 44 years earlier by providing the undoubted star — Jean-Claude Killy — the skiing sensation who became a triple champion.

Next up was Albertville, which became the first city to host both the Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games in 1992. This, too, was growing with 1,800 competitors, including 488 women from 64 countries. The star of the show was the great Italian skier Alberto Tomba, who successfully defended his giant slalom crown.

So what can we expect from Paris 2024 after a century since the Olympic rings were draped around the Eiffel Tower? There will be the usual sprucing up of the city that will include the renovation of the fire-damaged Notre Dame cathedral although only on the outside. It’ll look good on TV and for selfies but the interior is not yet ready.

The clean-up of the Seine is also in the “not quite” category and it may not be ready for the Open Water Swim competition. Giant vacuum cleaner-like air purifiers will also remove most of the pollutants but if it doesn’t sound like much of a rebuild, this is welcome news.

Just two new permanent buildings have gone up in an attempt to show the Olympics doesn’t need to create a herd of white elephant structures every four years. There will be 60km of new cycle paths, thousands of bikes for rent and all the monuments are getting a clean-up. New hotels have been built and new recipes are being tried out in restaurants.

It is a sensible, sober, albeit mouth-watering approach that is relying on the old gleam of the City of Light to illuminate these Games — without blowing a financial fuse. De Coubertin would be proud even if his statue does get a dousing in the Seine from woke warriors. If it happens, he’d probably dismiss it with a Gallic shrug from the grave.

Let the Games begin!

This article first appeared on Jul 22, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.