Honesty, courage and respect help in giving cancer patients the best possible care, says Woo (Photo: Soophye)

Prof Woo Yin Ling chose to specialise in gynaecological oncology after completing her studies in obstetrics and gynaecology (O&G) at Trinity College Dublin because she felt it covered nearly every aspect of medicine, from the first to the last breath of life. “There is the joy of new life as a baby is delivered, to grief when dealing with terminal cancer. It also has its fair share of surgery and medicine.”

Treating women with womb, cervix and ovarian cancers requires compassion and skill. “It’s highly specialised but the area keeps expanding. So, although I was trained as an obstetrician in my earlier years, I’ve not delivered a baby for more than 15 years,” says the consultant gynaecological oncologist at University Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC).

On top of this, Woo is a clinician scientist. She pares that down to easy bites.

“The bulk of my work is clinical — I see patients in clinics, have surgical sessions and do rounds in the wards — and I find that most rewarding. As a clinician scientist, one acquires the skills, or at least should, to translate a research question into something that will benefit patients and vice versa. Knowing the clinical needs in the local setting helps with clinical research.”

To train as a scientist, Woo spent three years doing a PhD in pathology at the University of Cambridge. “I did not plan on spending so many years learning, but the journey was worthwhile. Yes, a lot of the work I do is carved out from my personal time, but I’m okay with that. It’s something I enjoy doing … well, most of the time.”

Woo’s dedication and sacrifice have resulted in good work that has garnered global recognition. On Oct 28, she was one of 12 recipients of the 2021 FIGO Women’s Awards given by the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). First presented in 1997, the awards recognise women who have made significant contributions to the field.

London-based FIGO collaborates with global, regional and national organisations to promote the well-being of women and to raise the standards of practice in O&G. Woo was nominated by the Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society of Malaysia for her work in cervical cancer.

On Nov 17, she received a letter of commendation from the World Health Organisation acknowledging the work of the Rose Foundation and Malaysia in responding to WHO’s call to make cervical cancer a rare disease in the country.

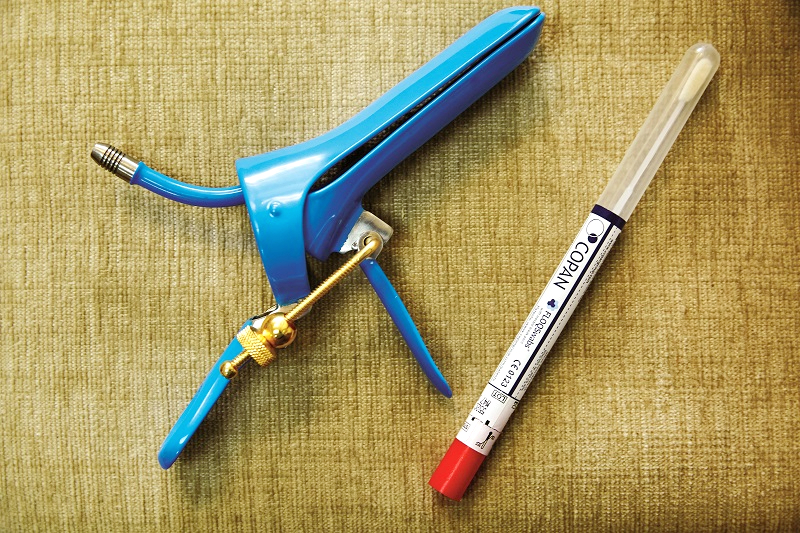

The foundation, set up in 2019, designed the Rose programme specially for Malaysian women, using a revolutionary approach to cervical cancer screening: self-sampling by women themselves instead of a pelvic examination by a healthcare professional; HPV testing instead of a pap smear diagnostic test for abnormal cells; and using a secure digital e-health platform to communicate follow-ups to patients through their mobile phone.

On Nov 17 too, organisations worldwide celebrated their achievements in working towards making cervical cancer — which is associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV) and can be prevented — a rare disease. “Malaysia is very well placed as we have a good HPV vaccination programme. We just need to increase the uptake of HPV testing,” says Woo, who was drawn to pursue O&G by inclusive teachers.

“Our lecturers had a culture of including medical students in their daily work — we were part of the team. This quote by Benjamin Franklin rings true for me: ‘Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I may remember. Involve me and I will learn.’”

As a young trainee, she worked with very encouraging doctors, in particular Dr Noreen Gleeson, a gynaecological oncologist who recently retired from Dublin’s St James Hospital. “I observed how she treated her patients and what it meant to them. It was an eye-opener for me. I sat with her as she counselled patients and their families — there was compassion. I assisted her in complex surgeries — she was extremely skilled. I had a role model.”

After two decades of training and working in the UK, Woo returned to Malaysia in 2010 and joined UMMC. Coming home — “I was delivered in 1972 in Assunta Hospital, Petaling Jaya, by Dr R S McCoy” — was always part of the plan. It was the timing and goal posts that kept changing, she says.

As a medical student, Woo would return and do summer attachments at UMMC while many of her classmates took the opportunity to travel. The O&G head then was Prof V Sivanesaratnam, and she kept in touch with him as joining UMMC was always on the cards. “I remember him telling me to get as much training and experience as I could before returning. That was exactly what I did.”

Eleven years on, Woo enjoys practising medicine at UMMC as she meets Malaysians from all walks of life. There is a good mix of clinical work, research and teaching, she adds, and the clinical cases are often complex and challenging.

Did she experience a reality check after decades abroad?

“I think I’ve been quite realistic in my expectations. But you know, there will be challenges wherever you are. It’s not all rosy in high-income countries. They have a different set of challenges in the UK. Yes, we do have limited resources here and you work with what you have.”

Early next year, Woo will be working with the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition (WOCC) on its Every Woman Study: Low- and Middle-Income Edition, which will be rolled out worldwide.

Coalition director Frances Reid emailed her several months ago to ask if they could have a chat. “One thing led to another and now we have a Malaysian chapter. This really is the story of my life — I’m a firm believer of responding to opportunities.”

Malaysia was not part of the 2018 survey, conducted mainly in high-income economies. This time round, Woo thinks ovarian cancer patients in the country can benefit from the focus on low- and middle-income respondents.

She feels very strongly about clinicians and patients working together to improve the survival rate and quality of life for survivors. “The way forward in healthcare is to include patient involvement in policymaking and design interventions that take into account a broad section of their needs. In this particular programme, Celina [May Benjamin, a breast and ovarian cancer survivor] and I are the named leads.

“But this really is about the patients’ perspective and what is needed in Malaysia. We will execute a questionnaire designed by WOCC here and see the shortfalls and deficiencies identified by patients with ovarian cancer. Then we’ll take it from there.”

As for cervical cancer, Woo wants to reduce, if not completely eradicate, it in Malaysia. Serendipity has a hand in her mission. “I’ve been able to contribute because I’m in the right place at the right time, working with the right people.”

Her doctorate was on the interaction of the human immune system and HPV — in simple terms, how the body’s immune system works to prevent women from developing cervical cancer. That was in the early 2000s.

“Today, the world has the tools to eliminate cervical cancer and the WHO has made that a global call. I believe many in Malaysia are working towards that target. At the World Health Assembly in May, our government committed to the elimination of cervical cancer. I am but part of the movement to try to make it happen here,” says Woo.

_s1a8737a_1.jpg

Like the mentors she watched during medical training, engagement is key. “I think listening is important. Among the voices we must listen to are those of women and patients — we must. Gone are the days when doctors knew best. If you think about it, there is no point designing interventions if there isn’t going to be any uptake!”

In an interview a few years ago, Woo said what kept her going was “the privilege, the learning … what other people go through”.

In so many ways, “that sentiment has become stronger as I’ve had the opportunity to meet many more brave women since. Being diagnosed with cancer is one of the most emotional experiences for anyone. While it’s not a death sentence, it is a major blow to the individual and her loved ones. As their doctor, you have the privilege to [walk] with them during one of the toughest journeys of their lives”.

Woo does not think being cheerful and having a positive disposition are prerequisites for the job. “It is being honest, courageous and respectful that helps.

“I’m under no illusion that I can cure everyone. My responsibility is to ensure each patient gets the best possible care — and that does not mean the most expensive — from his/her perspective. This means having some knowledge of who they are and where they are in their lives. It also means being honest enough to tell them the truth when their options for curative treatment are limited.”

She tries not to take cases home but admits one cannot totally dissociate from them completely. “I won’t say work gets me down but it’s natural to feel sadness when patients pass on.”

Looking back to March 2020, Woo says Covid-19 has caused a major upheaval and disruption in all aspects of life. “I believe we’ve not even experienced some of the consequences of the pandemic. I don’t think it was just cancer that was sidelined but, yes, it did have a very negative impact on those with cancers. At UMMC, we were still able to manage our patients but there was some level of prioritisation.”

She has had to juggle her time in the last year, with two children at home, patient care, writing papers and her work as a trustee for the Rose Foundation. Like many who looked to nature to cope and unwind, she turned to gardening. “I think there are many parallels when it comes to gardening and life.”

There is also quite a bit of family support, with her teenagers — “they’re a real delight” — and three generations living under one roof.

Does she have any happy news to share on cancer?

“There are many improved and new treatments in the pipeline. But the real improvement comes when all women have equal access to them. The financial implications of new therapies can increase the equity gap between those who can and those who cannot afford,” says Woo.

“We cannot just work towards better treatment for some. It must be better treatment for all. So, what will give us hope is a commitment from our government to ensure that every Malaysian’s needs are looked after.”

LIVING WELL, WITH RESILIENCE

Celina May Benjamin has battled both breast and ovarian cancer in the last three years. She was first diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer in 2018 and high grade serous epithelial ovarian cancer exactly a year later. Both are aggressive cancers and she is now under the care of Prof Woo Yin Ling, who approached her to support patient advocacy work under the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition. Celina, who stepped up to the task, shares plans for that in the country, as well as her cancer journey.

I was relatively healthy up to August 2018, when I felt a breast lump while in the shower. I immediately went for a mammogram and an ultrasound. The radiologist didn’t like the look of the lump and referred me to a breast surgeon in a private hospital. A biopsy confirmed I had triple negative breast cancer, an aggressive form of breast cancer. The date of surgery was set and, subsequently, everything happened in clockwork fashion.

With cancer, I have learnt it is always best to set emotions aside and focus on what needs to be done clinically first. Also, always heed your doctors’ advice and know you are in good hands. Trust is critical in the wellness journey. I responded well to the surgery and even managed a quick trip, planned earlier, to Belfast — I took my niece there for her tertiary studies — as chemotherapy would only begin three weeks after the operation.

I underwent six cycles of chemotherapy and 25 radiotherapy sessions. I was fortunate my cancer was stage 2A and I was able to do a lumpectomy instead of a mastectomy.

Exactly one year later, a series of tests I did after completing my chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatments showed an elevated tumour marker. A PET scan and other tests, including an MRI, confirmed I had stage 3C ovarian cancer. I had a total hysterectomy and the gynae-surgeon told me he managed to do optimal debulking and removed traces of the cancer which the human eye could see.

Again, I was put through six cycles of chemotherapy, which I responded very well to: My CA-125 was normal after the third cycle. For maintenance, I took a drug called Olaparib for three months before I relapsed. It was back to chemotherapy and I was given a more targeted medicine. However, I didn’t respond after three cycles and the oncologist changed the regime to the more conventional chemotherapy drugs, which worked. By October 2020, my CA-125 marker was normal until July this year.

_s1a8657a_1.jpg

I have since relapsed and am at a tough part of my journey. Three weeks ago, I underwent pleural fluid drainage in my right lung — 1.3 litres were drained. The first time last year, 1.75 litres were drained. This time round, my oxygen level dropped to 84 in the hospital and my haemoglobin was low. I also had intravenous albumin, given its low level in my blood. For the first time in my life, I had a blood transfusion too. I recovered well and managed to do my third weekly chemo session two days later. The cancer has progressed quite rapidly over the last month but I’m grateful I’ve been able to cope resiliently.

How have I managed with two cancers? I would say it is not with my own strength. Many factors come into play and the first is to place priority on prompt medical treatment. You will be inundated with suggestions of natural products that can be used instead of standard cancer treatments. Cast these aside and listen to your oncologist. There will be moments of fear and anxiety as you grapple with the truth of mortality. I have learnt to live in the present and it is not easy.

I am often reminded of the William Blake poem, Auguries of Innocence: “To see a world in a grain of sand / and a heaven in a wild flower / Hold infinity in the palm of your hand / And eternity in an hour.” It inspires me to live courageously, explore the world of extraordinary possibilities and have a meaningful life even as I face the unabated storms of advanced metastatic ovarian cancer.

There have been more months of treatment sessions than recurrence-free periods. My challenge has been always in maintenance, to have sustained progression-free survival. I have relapsed every year since 2018 but have responded well to chemotherapy, which I realised is an ally, and not the enemy.

It has always been in my plan to move from private medical care to University Malaya Medical Centre once I retire in 2022, as I don’t have personal medical insurance and cancer treatment costs today are expensive. My treatments have cost close to RM1 million over two years, if you include targeted medicines such as immunotherapy. Moving to UMMC was a natural option, as I had relapsed while being introduced to Prof Woo Yin Ling to consider supporting patient advocacy work under the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition. I consider myself very blessed to be under a leading gynaecological oncologist at this point of my journey.

Prof Woo’s approach to cancer management is more holistic and I appreciate that. New baselines in my blood situation have been set and I have done CT scans to ensure I don’t have blood clots in my pleural lining or lung vessels. I have what is called chemo-induced ITP, where my platelets are being constantly depleted and I need special medication for this. I still see my private medical centre haematologist to manage my ITP. There is a possibility to be eligible for a global clinical trial at UMMC soon and I’m looking forward to learning more about my cancer through this trial.

Ovarian cancer is often described as an elusive disease with symptoms mimicking other, less serious, conditions, resulting in delays in diagnosis. As the number of cases in the country rises, there is a clear need for greater social awareness to educate women and address the challenges survivors face. While other female cancers are seeing significant progress with detection and prevention, there are currently no reliable screening tests or vaccination programmes for ovarian cancer.

Ovarian Cancer Malaysia ([email protected]) is a partner of the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition. Our tagline, Living Resilience, captures in essence the experiences survivors face and we want to identify common needs and solutions.

I am the patient support lead in advocacy and external engagement, but it is early days. We are taking simple steps to build knowledge and include more women across the country. Rather than monetary aid, we are looking at employability for women with cancer because patients are often boarded out medically even though they are still productive and need some form of employment to be financially sustainable.

There is also the coalition’s Every Woman Study, launching worldwide early next year, which focuses on low- and middle-income women. We are aligned with its priorities — to ensure the best chance of survival and the best quality of life for women with ovarian cancer.

Malaysia is included for the first time and the lead clinician for this survey is Prof Woo. Our support group will use the findings to formulate areas of priority. Potentially, it could be gaining better access to medical treatment, especially for those in remote areas, creating financially supportive solutions for survivors and helping women overcome fears of social stigma linked to ovarian cancer.

As survivors, we all know we need to be vigilant and disciplined in our cancer care. What is inspiring is that while we are all on a common course, each of us has a unique experience to share. We are developing a buddy programme and we believe this can help us engage with one another and women out there.

Often, the conversations of many are on healing. I have come to realise it is not so much healing but resilience that I need to battle on, with the hope I will live well with each new day that I have.

This article first appeared on Nov 8, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.