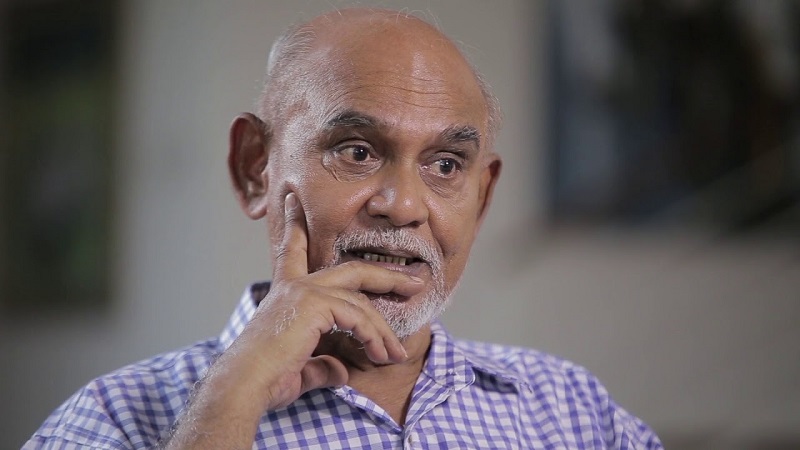

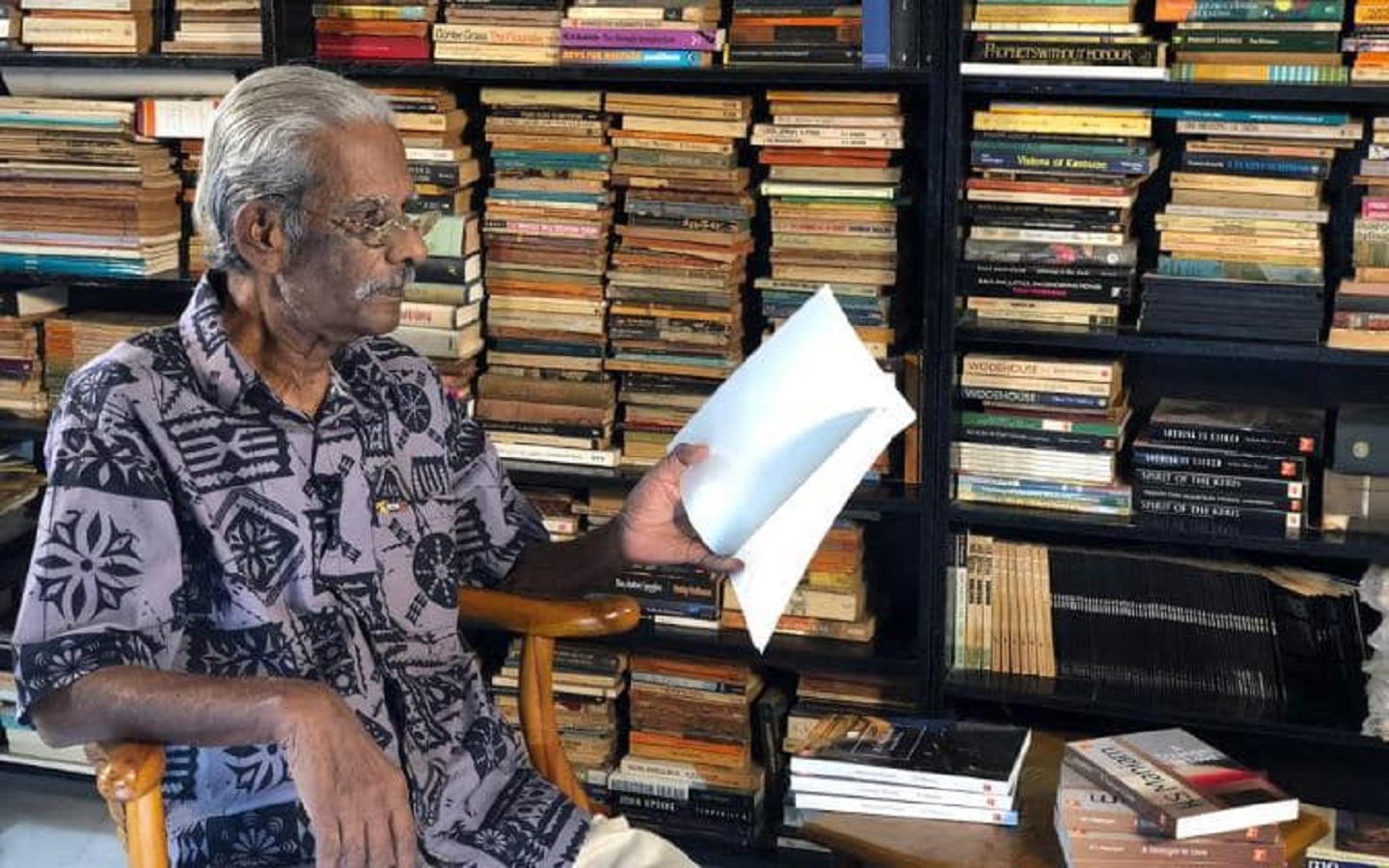

Maniam’s writing has touched on issues pertinent to Malaysia that transcended generations (Photo: Five Arts Centre/Jo Kukathas)

“The tiger I’m going to show you can’t be shot,”

“I’ll see it and possess it!”

“Nobody can possess it.”

These are the lines from KS Maniam’s famous story Haunting the Tiger (1990), which broke and reformed a lens upon which Malaysian readers viewed the idea of identity. The story spoke of a second-generation Indian immigrant, Muthu, who tries to assimilate into the local culture – all of which was portrayed through a metaphorical journey of hunting the tiger.

The majestic striped animal, a national emblem that represents the country’s spirit and soul, is posited as metaphor for land. By hunting the ‘tiger’ then, Muthu is seen to be searching for attributes that would make him one with the land, a native of the country.

It’s a familiar narrative that still strikes a chord among us as themes of belonging and racial tension continue to be relevant today. The main takeaway from Maniam’s stories, whether you’re ploughing through In Return (1981) or In A Far Country (1993), which reflect attempts of people trying to put down roots in Malaysian soil, is that the past is always present. Maniam, who illuminated our realities through myths in incandescent prose, took the canon and broke it open.

Which makes his passing even more poignant.

Born Subramaniam Krishnan in 1942, the prolific writer was born in Bedong, Kedah and raised in a hospital compound where his father worked as the hospital’s laundryman. After Maniam finished school in the 1960s, he attended the Malayan Teachers College in Brinsford Lodge, England before returning to Malaysia to teach in rural schools in Kedah. His academic career commenced in 1979 when he was appointed to a lectureship in English at the University of Malaya.

His books were not the only literary gems that shaped the course of Malaysian literature. One of his most famous plays, The Sandpit: Womensis, performed in 1988, discussed the mental conflict of his female protagonist as a result of a polygamous marriage in a working-class Indian family.

Maniam’s repertoire was a formidable melding of mind and heart, of intelligence and insight. He gloried in the beauty of language, gifting the world words that challenge us to confront and reckon with who we are as a person and a nation.

Rest in power.

Tributes from the literary community:

Eddin Khoo

Founder of Pusaka

Through his invocation of the experience of indenture, KS Maniam wrote powerfully of this land. Few could enter the realms of suffering and the subliminal with such visceral intensity. I came to his work through a short story entitled Mala, which begins with a description of a Kali ritual. The colour in those passages haunts me still. Always beautiful, brutal and courageous, KS Maniam – what an authentic voice. May you rest in truth Sir, your truth.

Mano Maniam

Thespian

KS Maniam made a case for Malaysian Indians when no one else would, and gave them a voice that they never had through his wonderful work. I think I’ve seen all his plays, and how he made sense of the estates and the labour class, and bring that to the fore – and it wasn’t just narratives, but characters and issues, too. We owe this man so much, who gave a voice for the voiceless fist generation of indentured labourers who are the backbone that this nation’s early start rests on. We’ve lost a gentle giant of Malaysian English literature.

Dipika Mukherjee

Author and sociolinguist

I first met KS Maniam when we were editing the Merlion and the Hibiscus for Penguin. He was possibly the most curmudgeonly writer associated with this project, and refused to give us the rights to use any of his short stories until he was paid at least a token sum. Penguin was launching a Malaysian/Singaporean anthology to be aggressively marketed worldwide and in 2002; this seemed like a golden opportunity to have the work of our writers accessible globally, but no, Maniam just would not budge.

He taught me two very valuable lessons at a time when I had started to flirt with the idea of creative writing but had written nothing publishable. The first one was to Write your truth, even if no one wants to hear it. He was feisty about not being edited in any way, and eagle-eyed about any kind of political correctness or censorship being imposed on his words.

The second lesson was Don’t give away your hard work for mere exposure, insist on payment. He was steadfast about this and it taught me how to honour my own work by always expecting payment for my time and talent. These two rules, established early in my own writing career, helped me leapfrog through the process of finding my own voice and finding a professional publisher. Rest in Peace, KS Maniam, and thank you for teaching us to write about Malaysian communities with authenticity and compassion.

Bernice Chauly

Author, educator

Hanna Alkaf

Author

Jo Kukathas

Co-founder of Instant Café Theatre, director, writer

Wong Phui Nam

Poet

Five Arts Centre