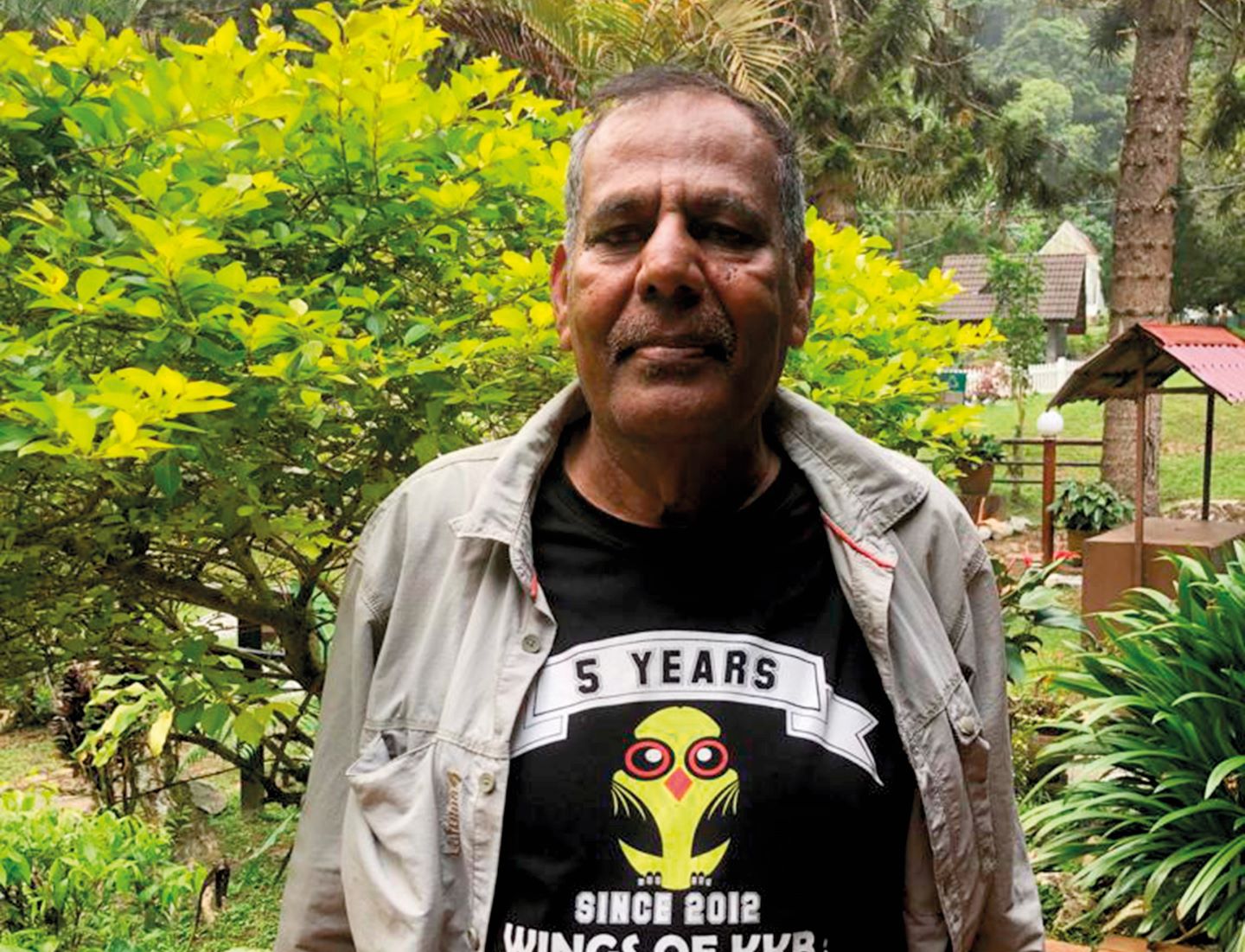

Keen to develop more interest in what has become his livelihood as well as passion, Durai has become an ambassador-at-large for birding (All photos: K S Durai)

Albert Einstein, Mike Tyson, Mick Jagger and Fidel Castro are a pretty unlikely foursome to lump together. Einstein studied extra-sensory perception in migratory birds; Tyson kept pigeons in a New York tenement loft; Jagger is an honorary Amazon rainforest ambassador; and, for the Cuban leader, birdwatching was a genuine hobby in an avian paradise. Neither Einstein, Tyson, Jagger nor Castro would ever be called nerds nor confess to having read such titles as How to be a Bad Birdwatcher or Field Notes from an Unintentional Birder. Self-deprecation was not their thing and not essential in the woods, but it helps.

But not even the enlistment of this rojak of brains, brawn, rock and revolution has altered our time-honoured perception of birdwatchers: To most people, they will always be slightly dishevelled, raincoat-wearing, nerdish biology teachers who drop double-barrelled names as often as their binoculars.

K S Durai is one of Malaysia’s best-known exponents. Dubbed the Birdman of Fraser’s Hill, the 65-year-old is a larger-than-life character whose reputation precedes him. If a BBC or National Geographic film crew came to Pahang looking for a long-lost white-bellied sea eagle, he would find it if anyone could. Both Sir David Attenborough and the late Duke of Edinburgh sought him out. Yet, even he admits that he became a birder by accident.

“It was around 1984 and I was working at the Puncak Inn,” he remembers. “I met a lady from Germany who asked me for a map and then about birds. I said, ‘I don’t know anything about birds’, but she asked me to join her. I think she felt more confident in the jungle with a local.

little_pied_flycatcher_a.jpg

“The first bird we saw was the Little Pied Flycatcher. A tiny thing, black and white. She spotted it, I still remember. She stayed four days and, as a thank you, gave me the Ben King book on Birds of South-East Asia and her binoculars. She even wrote articles about me and encouraged me to learn more. I took her advice.”

A relatively late convert, Durai says: “I was born in Fraser’s Hill and, as a boy, I had been in the jungle with my father, who was a policeman. But we were not really into birds then. And having gone to a Tamil school, I didn’t speak much English either. I started work as a labourer earning RM2.50 an hour.

“I picked up English and got a job at the inn as a clerk. I had just got married and was staying at the Glen Bungalow. I liked to go out after work and listen to the calls. I used to see the [sunbird] along the golf course. I studied slowly and gradually built up my knowledge by learning the sounds and then practising the calls.

“But I still only knew about 15 species when the German lady — a dentist — came back three years later. She insisted that I guide her again — even to Taman Negara and Kuala Selangor. It was only after her second visit that I felt like I knew what I was doing. Then I joined a friend and met a few foreigners whom I also learned from. And I bought a good pair of binoculars.

“In 1988, we started the Fraser’s Hill bird race. They had one in Hong Kong and I was invited to see how they did it. Then they wanted me to take part in ours and I won it the first three times.”

86404342_xl_normal_none.jpg

There were only three three-person teams — Malaysian Nature Society, Singapore Nature Society and Hong Kong Nature Society — in the inaugural event but although it grew, Durai decided to become a judge instead, a role that was necessary to keep the peace. It may not fit the birding stereotype, but competition can be keen, and sometimes over-keen.

“There are teams that will claim all sorts of things,” he says. “They claim to have seen some birds at night that are not nocturnal, some that haven’t been seen for 20 years and even some that are extinct! We have check points; there are arguments and it can get quite heated. In 2018, I had to walk out of the [judging] room to cool down at one point.”

A common problem is when sunlight affects the colour of the birds at different times of day. He explains: “The Rufous-browed Flycatcher can [take on a different hue] depending on the light. Like the Black-throated Sunbird, which can look purple in the sun.” He reels off the names with the familiarity of a football fan talking about favourite players.

On the cheating, he sighs: “The things people will do for a pair of binoculars … But they can be worth several thousand ringgit. If we had all the birds that people claim to have seen, we wouldn’t be worried about declining numbers.”

Durai says numbers are 10% down in the last few years and he worries about the habitat changing. He cites the planting of durian trees as a prime cause. Another is the increasing amount of concrete poured onto steep gradients to prevent landslides — as well as tarpaulin covers — that prevent birds from getting to insects.

Even the area’s signature bird, the Silver-eared Mesia, which this writer remembers being as common as pigeons in the garden of The Smokehouse 20 years ago, is becoming a rarity.

It was in 1997 that Durai left the hotel industry and was seconded by the Fraser’s Hill Development Corp to the World Wildlife Fund as nature education officer. He has also come under the wing of Tourism Malaysia and, at 45, was among the youngest to be honoured by the WWF for his work. He even rediscovered a bird thought to be extinct: the Malay Peacock-pheasant.

21b9ad30781a3312d12f4eb3aa07aa4c_xl.jpg

Fraser’s Hill is his own backyard and, like a London taxi driver, he has “the knowledge” of every nook and cranny and usually a few nests. He looks the part, too, with the bins, boots and a jacket with more pockets than a snooker table.

A notable personality in the former hill station once known as Little England, Durai has also campaigned successfully against high-rise property development and made frequent trips around the region as a judge and a speaker. But he still does his day job of giving bird tours.

Take one, and you will notice that he seldom ventures far off the road. “The trails are darker and you see fewer birds,” he explains. “Out here, it’s easier to see them.” He has long since acquired the sixth sense of knowing where the birds are — a combo of first hearing and finally spotting what is often a tiny silhouette barely visible to the untrained eye.

Sometimes, he will cajole it into the open so you get a better view and then he will whisper what it is. By the time you have looked it up, it is gone. But when he tells you it was an Orange-bellied Flowerpecker, all of 8cm long, you feel like you have just spotted a leopard in the Serengeti.

Yes, he has the calls too. Turn your head and you will swear you have just heard a Black-browed Barbet — at least that is what he tells you his imitation was. Or dozens of others in a burgeoning repertoire.

You will meet the occasional professional photographer pointing his artillery-size lenses into the wilderness, patiently waiting for a rare shot that might make his journey worthwhile. “A good shot might fetch a few hundred,” says Durai.

sliver-eared_mesia.jpg

And then there is his pet hate: the impatient types who play recordings to attract their prey. “[Apart from being] lazy and unprofessional, they confuse the birds. It’s bad for them and bad for the environment.”

We saw almost 20 species in four hours, but there are no guarantees in nature: When a friend hardly saw a thing or heard a tweet all morning, Durai offered a refund. But no time with him is wasted: He has the patter and the stories.

He tells of how the late Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, then president of the WWF, narrowly escaped an accident on the Hemmant Trail. “They built a new bridge across one of the streams for him,” Durai recalls. “And it cracked a second after he’d stepped across it. His security panicked but he didn’t even notice.” As for Attenborough, the Duke of Nature, he says: “He was fascinated by the trapdoor spider and we had a good chat.”

Keen to see more interest in what has become his livelihood as well as passion, Durai has become an ambassador-at-large for birding. He says: “In 2010, we started a bird race in Kuala Kubu Bharu with the Orang Asli, students and special children. And I helped set up one at Awana in Genting. There, we had only 20 teams but made sure every child got a tee-shirt even if they saw only a magpie robin. You have to get the children interested if we are to save the birds and the environment.”

The upcoming Fraser’s Hill Bird Race also includes children in its many categories and, as Malaysia’s biggest, it is one of Pahang Tourism’s main events, too. Spokesman Miss Nalini says: “It’s part of our ‘Green Environment’ programme and we were pleased with the response last year — the first since Covid. There were 74 teams and we usually attract visitors from six or seven countries.”

Much of this is down to Durai, the only qualified guide on Fraser’s Hill, and his ambassadorial skills inside and outside the country — an accidental birdwatcher with the best intentions.

This article first appeared on June 5, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.