Goalkeepers are crazy, clowns, saviours, thinkers, flappable and unflappable, and a breed apart. Pope John Paul II was one; so was Albert Camus, author of the aptly titled The Stranger. David James is another.

The ex-England keeper and Astro World Cup pundit has been all the above and more. Spice Boy. Celebrity Mastermind. Strictly Come Dancing star. Eco warrior. Armani model. Bankrupt. Artist. Manager. Not necessarily in that order.

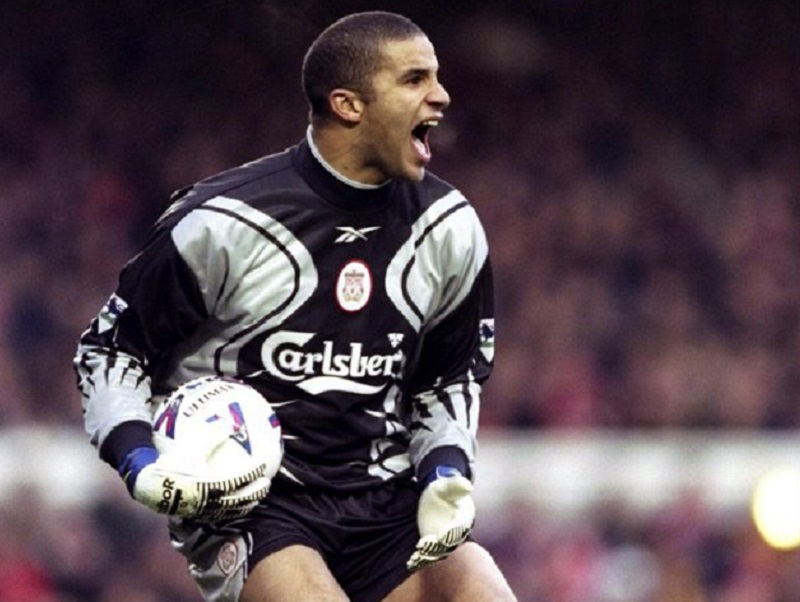

Of all the former stars that dropped (innuendo unintended) by the studio during the tournament, no one belied his reputation as a player more emphatically than the man Liverpool fans know as “Calamity James”. Nor turned his hand to so many good causes since hanging up his beekeeper-sized gloves.

On TV, we hear his in-depth analysis delivered in tones that are genuinely dulcet. But they give no hint of his colourful back story. Meant to be the next in a long line of fabled Anfield custodians, a few costly fumbles were enough for Scouse wits to do their worst — and the name stuck.

Catching up with him before a “Meet ‘n’ Greet” session between games at Shangri-La Kuala Lumpur’s Arthur Bar & Grill, he comes across as a man of many parts, who is now making saves of a very different kind.

It is often said that athletes “die” twice, the first time being when they retire from sport. Not James: he’s lived the fullest, most diverse and fascinating “after life” an ex-player could wish for. “How you follow it [a sporting career] is a human problem,” he says.

Now 52, he speaks in the same sotto voce we heard while he tried to make sense of a manic tournament. He adds: “There’s a propensity to be totally focused on your career, but when you leave, you don’t know where to go. Fortunately, I’ve always had other interests.

“Football is a 24/7 job and I had to focus on it to make sure my football ability was on show at the expense of those interests. I played 1,000 games in all competitions,” he says, before quipping, “[Lionel] Messi has just joined the club!”

david_james.jpg

Even the little maestro will not have the smorgasbord of options that James enjoys.

Although he is currently revelling in the role of pundit, it was not love at first sound bite. “I wasn’t sure I wanted to go into it,” he admits. “Watching and hearing other people assessing my performance; then assessing their valuation as being incorrect, cheap or glamorised in some way, I thought, ‘I just can’t do that’.

“But I was given an opportunity with mock-ups of situations in matches to keep things real rather than glamorise or dramatise, and I got right into it. Before I come on the Astro floor, I will have done hours of prep and have lots of stats. I’m very analytical and the world of punditry suits my character.”

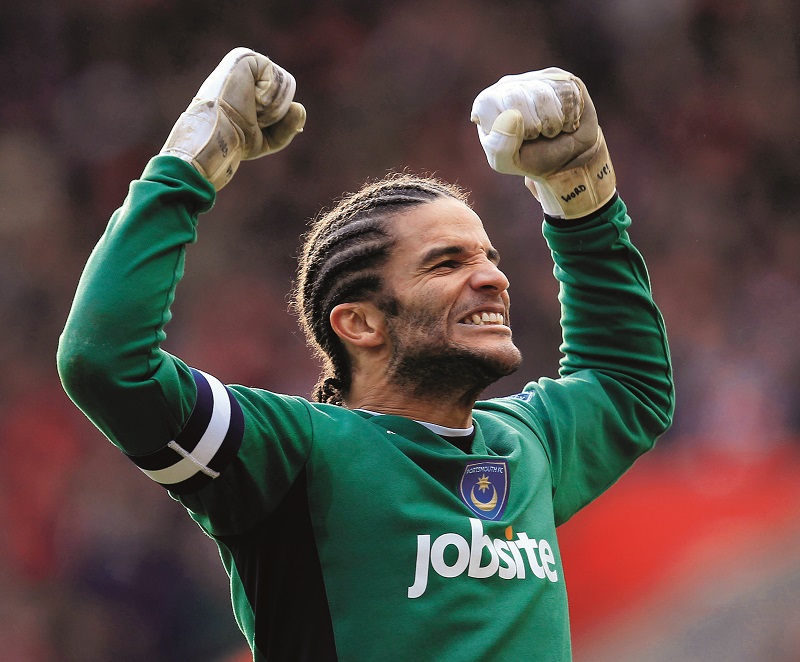

On the field, he didn’t win the trophies his talent deserved: a lone League Cup with Liverpool and an FA Cup winners’ medal with Portsmouth being scant reward from a career of 572 top-level games. It hit him when a flashy lifestyle and expensive divorce from ex-wife Tanya left him bankrupt. He had to sell his memorabilia to get back on his feet and could have done with a bit more.

He won 53 caps for England and was a proud owner of a clean sheet record of 169 games until Petr Čech beat it. He still has the most penalty saves (13) in the English Premier League. Another testament to his longevity was when he became the oldest World Cup debutant at 39 years and 321 days in 2010 — a record that has since been beaten twice.

From the Kop to Kerala, it has been quite a journey. He is still on it if you count driving an ancient Chrysler on rapeseed oil as actually travelling.

“It wasn’t when it broke down on the motorway with four kids in the car,” he concedes.

Home is in Devon, deep in the English countryside and far from the madding football crowd. He is restoring an old house, but it does not mean he has gone out to pasture: the house gets done between all manner of projects far and wide. And his partner is from Hong Kong, which often brings him in this direction.

2010-02-13t120000z_1081857123_gm1e62d1sat02_rtrmadp_3_soccer-england_1.jpg

In his prime, he found himself in Malawi on an AIDS awareness mission, but ended up establishing a foundation to help maize farmers. His last port of call was India and, in between, he would provide irrefutable evidence that goalkeepers are different: he has the soul of the individual in a team game.

Kerala Blasters was his last club, it was anything but a backwater. He had two stints, the first as player-manager where he led them to the Indian Super League (ISL) playoff final in 2014.

He says: “When the ISL kicked off, they were the first professional team. Kerala is one of three football hubs in India. My first home game was the fifth of the season because the stadium wasn’t ready. We weren’t in great form going into it and wondered if anyone would support us. Thirty thousand people turned up.”

Four years later, as a non-playing manager, he did not last long.

“I was sacked,” he says, “because the owners were only interested in results.”

When I suggest they sound much like owners everywhere even if cricket legend Sachin Tendulkar is one of them, he ripostes: “In my environment, people get an opportunity to better themselves. I want people to feel like they belong.

“They were asking for time off for further education. Physios wanted to take on new practices and skills, so I had to manage the team around that. When I left Kerala Blasters, I know that people had improved under my management. But, no, I’m not longing to go back into it.”

As the son of a famous Jamaican artist, Joe James, it is not surprising that he has dabbled with the brushes. Joe died three years ago and there is still a gallery in his honour on the Caribbean island. But James himself, who was not close to his dad, says it is almost accidental that he is continuing Joe’s legacy.

“I was asked to paint something for a documentary about the World Cup and caught the bug,” he says. “Lockdown was my most prolific spell — I did loads and ran out of wall space. I found a lot of politics was creeping into the paintings. And I’ve even been drawing out here.”

He is also going green, but just because he was the last line of defence in a previous life, he is not about to join Extinction Rebellion. Instead of gluing himself to a landmark, he has opted for what he calls “a quiet campaign”.

“I like the environmental stuff,” he says. “Not that it’s going to change the world as I don’t think one fix fits all. But if there’s an opportunity to improve the environment and change people’s lives, I’m all for it. My mind tends to focus on different things at the same time. I like to do something for impoverished people. They should be given a chance.

“Take something like the water hyacinth, for example. It’s a pest plant and clogs up waterways. I spent a year in India and, as a keen gardener, I couldn’t help but notice this stuff. I used to watch it floating by and didn’t know anything about the oil it contains.

“But in Africa, they crush the seed and use it for cooking fires. Malawi has high deforestation as farmers there can’t afford fuel. If you can take a ubiquitous plant like that and do it on a big scale, it would mean those farmers don’t have to chop trees down. I’m looking into it.”

As we are in a hotel restaurant, it’s inevitable that James gets spotted. People will be imagining we are talking about the World Cup or Liverpool or any of the nine other clubs he represented. But, no, he is talking about using one continent’s waste to save another.

Finally, we get on to football where critics might say there was some waste, too, in those lost early years. I ask how he looks back on his time at Liverpool.

“I did have some fantastic games with them,” he answers. “But my one regret is that I was there during my twenties when sports science was nowhere. I took a lot for granted and even smoked! I’d been a smoker since I was 15 and was on 20 a day during my whole time at Liverpool.

“Things really changed at Aston Villa, which had a goalkeeping coach, Paul Barron, and I absorbed sports science like a sponge. I gave up smoking, trained properly, had a proper diet and my approach to football saw me fulfil my potential.

“I look at the time I was 36 and went to Portsmouth. I probably had my best two years there and I was 100% committed to being the best footballer I could be. It wasn’t that I wasn’t committed before that, but all the pieces weren’t in place. I always ask the question if this had happened when I was 20, who knows?

“Despite all that, the many Liverpool fans I’ve met in Asia have been so genuinely good and nice they’ve changed my value on what it means to be a Liverpool player.”

The World Cup is coming to a climax, so I have to ask where he stood on the Messi-Ronaldo debate.

He says with a laugh: “Messi was my favourite until Ronaldo let my son play with his friends when we met. But if it’s purely statistical, there’s no argument — it’s Messi.

“However, Ronaldo was going to trump him until the last few months, which have not been great [for the Portuguese]. In my humble opinion, it’s not just how many goals you’ve scored, it’s the way you’ve conducted yourself.”

In James’ case, it is how many he has saved. Once his media duties are done, he is meeting fans before analysing the evening game. With so many irons in the fire and the ability to focus on two at the same time, whether it’s the World Cup or water hyacinth, you feel he will acquit himself well.

After all, when you have played 1,000 games as a goalkeeper, saving the planet is something you can take in your stride.

This article first appeared on Jan 16, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.