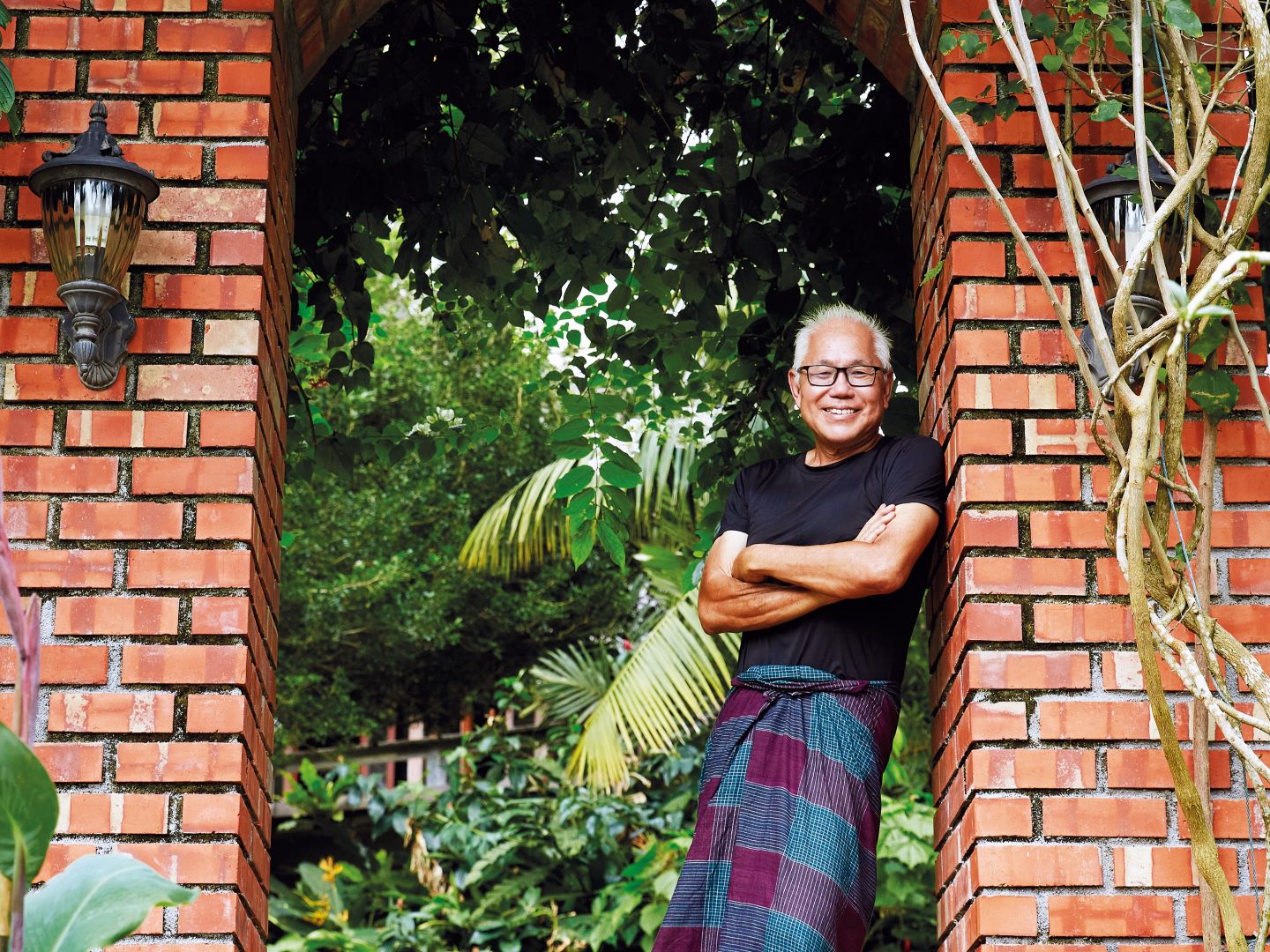

Lim envisions Langkah Suka as a utopian retreat-cum-biodiverse microcosm (All photos: SooPhye)

People often mistakenly think renowned Malaysian landscape artist Lim In-Chong (Inch Lim to all) named his sprawling estate Langkasuka after the ancient Hindu-Buddhist kingdom believed to have existed centuries ago in the north of the Malay Peninsula. Actually, the beautiful country home is christened Langkah Suka, Malay for “happy steps”. Indeed, it is a place where one cannot help but gambol about gaily or, for the more Zen at heart, engage in meditative walking. After all, being surrounded by lush nature is akin to paradise for most people. “Langkasuka … too grand a title for this place,” laughs Inch as he walks us through the grounds. “Teratak Katak (a frog’s wooden shack) would have been a nicer and more humble name, I think. Besides, we have at least 10 species of frogs on the land. But, oh well, Langkah Suka it is and Langkah Suka it will be ... at least for now.”

Big on biodiversity

It is also an indisputable fact that land, gardens, trees and plants have it best under Inch’s care. Arguably the country’s most celebrated landscape artist, he nevertheless arrived late to the plant party. Two decades after graduating from Canada’s Trent University and exploring various career paths — from odd-jobbing to teaching and dabbling in different ventures, including helping manage one of his late father’s businesses in Malaysia and Singapore — and in his 40s by then, and without any official qualifications (he has since formalised things a little with a master of design and architecture from RMIT University, Australia) except an inherent passion for form and flora, Inch plunged headfirst into landscaping.

as1a3139b.jpg

Among an esteemed circle of peers, his knowledge of tropical plants is said to be unrivalled. And his touch with plants? Positively Midas. A slew of awards from the world’s top competitions and gardens festivals, such as the Chelsea Flower Show, Singapore Garden Festival, Philadelphia Flower Show and Japan’s Gardening World Cup Flower Show, including an unprecedented four medals at the latter on his first try, gives gloss to his portfolio. Then there is Inchscape, his eponymous 18-year-old practice, housed in a pre-war shoplot in the heart of old Kuala Lumpur, that is sought out for all manner of impressive projects, from show gardens, luxury hospitality and high-net-worth homes to national park development board and state government consultancy, theme parks and even a bear sanctuary.

Hailed as Malaysia’s version of Geoffrey Bawa — the late, great Sri Lankan master who is considered one of the most influential Asian architects of his generation and de facto leader of the Tropical Modernist movement — it is apt then, that Inch has his very own version of Lunuganga, Bawa’s sprawling country estate in Bentota, a few hours’ drive from Colombo. With Inchscape well established since 2006, the Malaysian master now has a little more time to work on Langkah Suka, which he envisions as a utopian retreat-cum-biodiverse microcosm, fitting in perfectly with his personal interest in green developments and renewable energy.

The expansive estate now spans a total of 10 acres. “Well, I needed a garden,” he says, tongue-in-cheek. “Ten acres is wonderful. Thirty is better. And 50 would be best! I didn’t have the money then, but my late father bought the land in his name and willed it to me … He passed away about 10 years ago. I’m not being greedy, but you really do need scale to learn how man relates to nature and vice versa. This garden is my mini experiment … a place where people can learn lessons just by being here… lessons on architecture, gardening or life itself.”

Using gut health as an analogy, Inch breaks it down for the layman. “Just as our digestive system needs good bacteria, it’s the same with the forest. We need to look at developing sustainability but with biodiversity! It’s a tragedy how we keep cutting down jungle and planting only, say, oil palm. This will just impoverish the soil, which many don’t realise is, in fact, the building blocks of life itself.” Inch elaborates by explaining how certain microbes can grow and flourish only once trees reach a certain age and size. “Most people might not be aware that plants can’t absorb a thing without microbes. And that is why when I first started gardening at Langkah Suka, it was a struggle for the first 10 to 20 years. Once I successfully built up the microbial level using my own compost mixed soil, things began to take off.”

as1a2891b.jpg

As if to prove Inch’s point, Langkah Suka is veritably teeming with life. There are thousands of species to discover alone in the estate, 700 of which were planted when he first started working the land. There are, for example, Amherstia nobilis and its gorgeous flowers, “considered one of the most beautiful tropical trees in the world”, he notes approvingly, as well as Nyctanthes arbor-tristis, also known by its equally evocative name of “night-flowering tree of sadness”, and Millingtonia hortensis, or Indian cork. The latter, with its heady fragrance and bell-shaped sepals, is a sight to behold when in full bloom. “We have so many animals, too. There are wild boar, giant squirrels, slow loris, porcupine, mousedeer, snakes, tree shrews, colugo … and, further down, where the sea is, you can sometimes find otters. And don’t forget the birds. We have noted more than 100 species, just from casual observation.”

The early days

Born in 1955 in Batu Pahat, Johor, the second of six children to a businessman father and homemaker mum, Inch unashamedly declares with a laugh that his younger self was a “wild child, but in the nature-loving sense”. Somehow managing to incorporate as much of the natural world into his daily life as possible, he enjoyed hanging around the neighbourhood waterways and simply observing life. “The streams then were so clean and clear, and filled with fish! I remember seeing barbs, rasboras, gouramis and Siamese fighting fish. I also kept all kinds of pets, including owls and baby palm civets, which I spent many nights feeding from a bottle.”

as1a3175b.jpg

Despite his keen knowledge of the natural world, Inch admits: “[I was] not very academic and, frankly, hated studying. Nature — and anything that moved — was, honestly, what fascinated me. As a child, I particularly loved dragonflies. I thought them the most incredible creatures ever.” Now older and infinitely wiser, he also ruminates on the reasons behind his drive to make Langkah Suka more accessible to the public than ever. And by this, he means turning part of it into an eco-conscious retreat as well as a place of study and reflection. “As you age, you start to wonder whether what you are leaving is truly of value,” he muses wistfully. “It has to be something people can appreciate or learn from after you die.”

On the sudden segue into memento mori, Inch states: “There is no life without death. This is what working with nature has shown me. Nature is truly the best teacher. And there is no way life can be supported without death in one form or the other; if not, how would you sustain yourself? Death gives life. It’s the ultimate paradox, but it is also the truth.”

Creating bliss

As one tours Langkah Suka, more comparisons with Bawa will inevitably be drawn, a fact that makes Inch smile. (In another parallel, the Sri Lankan master, too, entered his profession late in life, obtaining his architecture degree only at the age of 38.) “Bawa was a genius, no doubt. If you visit Lunuganga, you will see how he designed the landscapes or cleverly placed statues just so, allowing the land to reveal itself to you … but only if you take the time and trouble to see. I am trying to do the same via my architecture and landscaping. It would be nice to have people come and let the trees and plants impart their knowledge subtly. There is nothing like experiencing the awe of a truly big tree in person or planting something that goes on to thrive.”

pelagodoxa_henryana.jpg

Although plans are still being finalised, architecture aficionados, nature buffs or those with a proclivity for exotic plants can look forward to Inch’s master plan of an eco-conscious retreat that is on the cards. He is still undecided whether to entrust the management of Langkah Suka to a hospitality company or run it himself, but work is already underway on a six-bedroom Malay house, brought over from Alor Gajah, while Langkah Suka’s existing Pavilion and infinity swimming pool are being cleaned up in anticipation of guests and private events. “All this is my idea of what honest architecture should be. Everything you see was all covered in secondary forest growth and old rubber trees. I slowly worked at it over the years. The trees have since grown and, while they grew too slowly for my two children, the first thing I will do, should I have grandchildren, is to build them a tree-house,” he says.

Meanwhile, those lucky enough to be asked to stay would undoubtedly enjoy the property’s lush wildness. The Strait of Malacca is close enough to buffet the land with sea breeze. You will need at least a full day or two to truly appreciate the dazzling variety of flora as Inch’s landscaping genius is showcased to full effect according to category. There is, for example, the Scented Garden, where all manner of fragrant flowers are planted, including lilliums from Sri Lanka, frangipani and plumeria trees, roses — impossible to grow well in the tropics and, yet, in Inch’s hands, beautifully buck the trend — and other wonderful plants that send perfume wafting through the air when the breeze hits just right. “There is nothing I like better than sitting here at the end of the day,” he says contentedly.

The Vertical Garden houses a seed deck, barbecue area, water features and lily pool, complete with the awe-inspiring Victoria Amazonica, or giant water lily, whose enormous leaves can spread up to 3m wide and support the weight of a small child. A further meander leads guests to the Palm Garden (do not miss marvelling at the Pelagodoxa henryana palm, whose seeds can fetch up to A$350, or RM1,010 each). There are also the Ornamental Garden, vegetable patches and orchards to explore, planted with the usual suspects such as jackfruit, papaya, rambutan and cempedak as well as the always-coveted durian, mangosteen and pulasan.

Meals, always starring the freshest fruit and vegetables harvested à la minute, seem better than what is served at most Michelin-rated establishments these days, demonstrating the true power and flavour of homegrown produce. There is a sweetness in the leaves and greens that has to be tasted to be believed. As night falls and the pitch blackness outside invites deep slumber, broken only by the faint glow of a nearby firefly or two, the thought of being able to book oneself in for a sybaritic stay in the not-so-distant future is dizzying. “Now you understand why I don’t mind commuting between the office in KL and Batu Pahat weekly,” Inch grins. “Every time I leave, it is like tearing myself away from paradise. I guess that’s what Adam and Eve must have felt being kicked out of the Garden of Eden.”

For now, and until Langkah Suka is ready to open its doors to the paying public, it looks like heaven has to wait.

This article first appeared on Oct 21, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.